Dudley Do-Right is the main character in a vintage cartoon series from the 1960s, but he didn't start out that way. Mr. Do-Right was originally a supporting character in another cartoon, "The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle." That series featured a sentient moose and a flying squirrel who teamed up to save the world from Russian spies Boris Badenov and Natasha Fatale. As an aside, "Badenov" is not an actual Russian surname. It is a reference and play on words to real Russian tsar Boris Godunov (pronounced "good enough")

Mr. Do-Right became so popular in his own right that he was granted his own show. "Dudley Do-Right of the Mounties" ran for several years. A live-action movie was filmed in 1999.

Mr. Do-Right had a difficult name to live up to, since in general he could do no right. He messed up each time he tried to save the day. It was frequently his horse who actually figured out what to do. The program was filmed—or, more accurately, animated—with backgrounds of the Canadian Rockies. In a typical episode, we'd watch dastardly villain Snidley Whiplash tie the heroine, Nell Fenwick, to the train tracks in front of an oncoming train. Dudley would try to save Nell, but it was his horse who would make the rescue. Plot resolved, they do it again in the next episode.

The show's graphics, even in the live-movie version, are appropriately cartoony, with depictions of rocky crags, 19th-century locomotives and improbable-looking train trestles. One cartoon image of an unlikely train bridge is based on an astonishing real-life structure, the massive Steel Cantilever Bridge, which spans a gorge in Alaska near the Yukon border.

Cantilever Bridge Photo credit: Brian Brenner

Cantilever Bridge Photo credit: Brian Brenner

The Steel Cantilever Bridge was built as part of the White Pass and Yukon rail route. The route originally ran from the coast at Skagway, Alaska, north and east to Whitehorse, Yukon. The southeastern Alaskan coast has a connected line of deep fjords that provide ships protection from the open Pacific Ocean. The fjords are know as the Inside Passage. Skagway is located in the crook of mountains at the northern end of one of the fjords. Moving inland from the coast, the terrain dramatically rises up several thousand ft.

Skagway by Christopher Michel/Creative Commons

Skagway by Christopher Michel/Creative Commons

Construction of the railroad was prompted by the Klondike Gold Rush at the end of the 19th century. When gold was first found along the Klondike River north of Whitehorse, thousands of prospectors ascended the slopes from the Alaskan coast. It was a perilous journey with resulting hardship and loss of life. Many were not prepared for the trip. To address this problem, the Canadian government required that all prospectors entering the Yukon bring a year's worth of food and supplies.

Getting the bulky supplies to the gold field required many trips up White Pass at the top of the trail from Skagway. Many horses lugging the goods died on the steep slope, so the trail was informally known as the "dead horse" trail.

The Canadian government authorized construction of the narrow gauge railway to ease the way for prospectors. Unfortunately, the railroad ultimately did not provide much help. When gold was discovered to the west in Nome, Alaska, the Klondike Gold Rush petered out shortly after the railroad line was opened.

After that, the route provided support for mining operations. The railway was the primary route for shipping ore out of the Yukon to the port at Skagway. During the period following World War II, the railroad's use for shipping was gradually reduced as mining decreased. It stopped running altogether in 1982.

The last and current chapter of the story focuses on tourism. The sheltered fjords of the Alaskan Inner Passage were discovered by the cruise industry, and in summer several large ships would set sail for ports along the Alaskan panhandle. The railroad line was refurbished from Skagway to the town of Carcross, Yukon, and reopened in 1986. (The segment from Carcross to Whitehorse is no longer used.)

Today, after the boats dock in Skagway, tourists descend on the scenic town where they can double or triple the town's population. Trains run almost to the edge of the docks to pick up tourists for the ascent up the mountain slopes. Unlike 19th-century prospectors, these well-fed and rested passengers enjoy a spectacularly scenic and lazy ride up the mountain and across the fierce chasms. At the end of the line, they are deposited in Carcross, Yukon, where they encounter the now thoroughly civilized Canadian wilderness, featuring knick-knack shops, Yukon coffee and a farm with sled-dog puppies ready for petting.

Construction of the original line featured heroic feats. In those days there was no Autocad or smartphones, and use of engineered plans was limited. Constructors lacked detailed survey, and they staked the route as they built it. One of the biggest challenges was crossing the canyon near the top of White Pass. The resulting bridge was a marvel of its time, with unique triangular trusses that join to form a three-hinged structure.

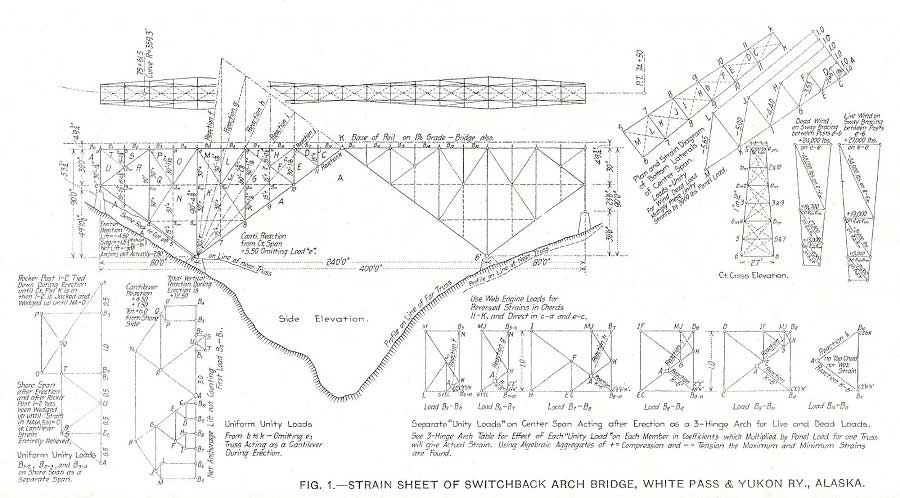

Information about design and construction of the bridge can be found in an Engineering News article called "The Switchback Arch Bridge of the White Pass & Yukon Railway" from March 28, 1901. The original article was scanned into a blog entry at RailsNort.com and can be found here.

The article provides a view of late nineteenth century bridge analysis and building. Calculations were limited not so much by theory but by the difficult process of calculating. With a slide rule, you can only do so many finite element analyses (i.e., none). The original hand-drawn blueprints had stress tables for the truss members, and the analysis was governed by basic assumptions with no partial fixity or secondary moments.

Original Strain Street, reprinted RailsNorth.com, originally from Engineering News, March 28, 1901.

The overall approach was simplified by detailing three hinges, two at the base and one in the middle. The bridge seems to connect at a sharp point in the middle, in part to make the analysis easier by forming a center hinge. The two sides are evaluated as two separate simple spans.

Without advanced analysis, nineteenth century bridge engineers relied on "form follows function." Back in the day, a bridge was detailed to get the forces from point A to point B with no muss or fuss. There was no ability to design "startle structures" with leaning pylons or gaps in arches, as in the more recent bridge design approach illustrated by the photo below.

Samuel Beckett Bridge by William Murphy/Creative Commons

Samuel Beckett Bridge by William Murphy/Creative Commons

But the resulting bridge was dramatic and startling anyway.

The last train crossed in 1969. That year, the tracks were rerouted to a nearby tunnel and less ambitious girder bridge. Riding the train today, you can see the old truss bridge as the train crosses the gorge on the adjacent girder bridge. For a moment, it feels like you have been transported to a cartoon. The train pulls out of its tunnel, and there is the old bridge off to the side, an astonishing sight. Parts of the timber approach trestle have collapsed, but the main triangular trusses of the steel bridge are still intact.

A ride on the railroad reminds you of a different time and place. The scenery is heroic, with soaring mountains, sheer cliffs, canyons and dashing waterfalls. Without the railroad, hiking up White Pass and beyond to the Klondike gold fields of 1892 is hard to imagine. The weather is hospitable in the summer for maybe a few short months. But for the rest of the year, harsh Arctic cold bears down on the plateau with a wind-whipped fury. Building the railroad in this place was also heroic and difficult to imagine from the comfort of today's design offices. At first glance, the Steel Cantilever Bridge looks grand but improbable, as if it were inspired by the Dudley Do-Right cartoon and not the other way around. This impression is confirmed by subsequent views. You see it but still don't quite believe it. Look carefully as the steam engine chugs by, and you can imagine the ghost of Snidely Whiplash tying Nell Fenwick to the tracks. Dudley's horse will soon ride to the rescue.

Photo credit: Canadian Automobile Association

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment