When a piece of equipment breaks down on site, rental agreements, subcontractor contracts and other arrangements generally make it clear who gets to open the hood and start tinkering. But heavy equipment made in the last two decades increasingly relies on digital components for many basic functions. Embedded computer systems oversee electronically controlled hydraulics and regulate engine behavior and emissions-control systems. The tools to access these firmware and software systems are not always easy to come by, and in some cases repairs can’t be done without working directly with a manufacturer-approved dealer or technician. Some repairs may require a digital handshake to take effect.

With construction equipment—often relying on dealers and rental shops for repairs—there hasn’t yet been a huge outcry for more independent and self-performed repair. But over in the agricultural sector where equipment owner-operators are more common, some farmers have run headlong into the “right to repair” issue when it comes to servicing their own machines. And with legislative skirmishes playing out on the state and national level, there is an ongoing fight over who gets to fully service and repair modern, computer-reliant heavy equipment going forward.

“Manufacturers are saying ‘my stuff is too complicated, you can’t fix it,’” says Gay Gordon-Byrne, director of the Repair Association (formerly The Digital Right to Repair Coalition), a non-profit advocacy group organized around the issue. “Well, you definitely can’t fix it if the manufacturer doesn’t provide what is needed.”

The Repair Association’s efforts initially began by defending independent repairs of computer equipment, smartphones and other consumer devices. But as organizers found more and more industries relying on devices and equipment with embedded digital systems, their efforts have grown to encompass everything from specialized medical equipment to farming tractors and harvesters.

When something breaks, fixing it is a matter of getting the parts and tools you need as well as the schematics and manuals showing what to do. When an iPhone breaks, Apple sets boundaries on how much users and independent repair shops can tinker with it before needing specialized tools, but it’s a bit different with off-road equipment. Parts can be ordered, manuals are usually available and many mechanical repairs generally don’t require a dealer’s intervention. But the wild card is the embedded computer systems found in today’s machines, spitting out error codes and sometimes requiring firmware resets with proprietary files to get running again. And that’s where equipment manufacturers such as John Deere have drawn the line.

Parts and manuals are available for many independent repairs, but there are some specific firmware resets that require the intervention of an authorized dealer.

Photo courtesy Caterpillar

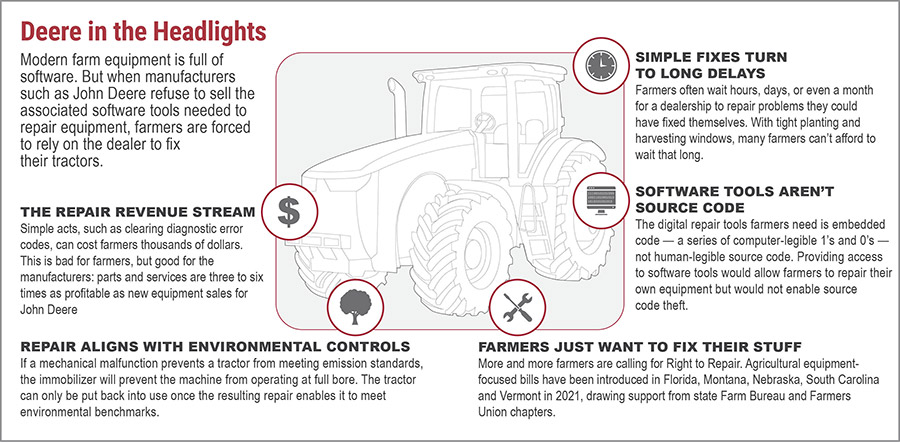

Deere has emerged as a vocal opponent of the right to repair movement in recent years, even drawing the attention of the general news media. A 2017 report in Vice’s Motherboard cited cases of some U.S. farmers downloading hacked and unlocked versions of their own tractors’ firmware from private online hacking forums, so they could perform resets of embedded computer systems that would otherwise require a trip to their dealer or authorized service technician.

Advocacy organizations such as the Repair Association have heard similar stories of farmers who tried to make relatively inexpensive repairs to their equipment, only to find it would likely take a more costly trip to the dealer to get firmware flashed so a machine would accept the new parts. “In the case of tractors, people would be better off not buying pilfered John Deere software produced through Ukraine or some other nonsense,” says Gordon-Byrne. She adds that such cases of getting hackers to rewrite firmware come from a lack of other options from manufacturers. “Maybe [manufacturers] need to make it possible for customers to repair without resorting to modification.”

Deere has taken steps in recent years to make their equipment interface devices available to users and independent shops, but still balks at releasing the software keys to let users completely reset the behavior of Deere machines’ engines and systems.

In a statement to ENR, a spokesperson for Deere said the company supports owners repairing their own equipment and is willing to provide the tools, manuals and online training to do so through its Customer Service ADVISOR service. But it objects to allowing any modifications to the underlying software in these machines.

“John Deere does not support the right to modify embedded software due to the risks associated with the safe operation of equipment, emissions compliance, and engine performance,” the Deere spokesperson told ENR. “We remain committed to providing innovative solutions that support our customers’ needs.”

But the opposition to repair advocacy efforts isn’t limited to just one manufacturer. The Association of Equipment Manufacturers (AEM), which represents many original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) that supply the agricultural and construction sectors, has taken a firm stance against both right to repair advocates and efforts to pass legislation at the state and national level codifying complete access to the repair tools and software for machines.

With such a charged policy issue, it often has come down to industry associations to speak for individual companies. Many of the OEMs, dealers and equipment-owning contractors contacted by ENR declined to comment on the right to repair issue, or deferred to their industry groups and associations.

“AEM and the manufacturing industry supports users’ right to repair their equipment, but we don’t support right to repair legislation,” says Stephanie See, AEM director of government relations. “Because it goes further than just repairing equipment. It goes into accessing the embedded code of the machine, and that can have multiple consequences for safety, liability, [as well as] data privacy and protection.”

Changes to the underlying firmware and software could allow for safety features or EPA Tier 4 Final emissions controls to be circumvented on equipment, See says. She adds that while AEM opposes any right to repair legislation intended for any industry, it also views it as a particularly bad fit for construction. “The construction industry truly is a very different business model than some of the other industries the laws target, and it just would not make sense to apply right to repair to the construction industry.”

“We don’t hear from the construction industry as much as we do from farms,” says Kyle Wiens, co-founder of the widely used repair website iFixit.com and a leading advocate of right to repair. “But it’s kind of like a frog slowly boiling in water, not realizing it until it’s too late. Is it an edge case to not be able to repair your equipment? We’ve got farmers who can swap out an engine in an F-150 [pickup truck] but can’t do the same on a tractor.” Wiens himself has an old tractor that he has been restoring, as well as a Deere 450C crawler bulldozer. “All mechanical,” he notes.

Wiens’ website is a repository of repair instructions for everything from iPhones to computers to trucks and tractors. In addition to including scans of old service manuals, volunteer users also regularly post repair guides with step-by-step photos and instructions, all available for free under open-source licenses. “Our current focus is power tools. We are currently the largest online resource for power tool repairs,” he says.

Deere takes a hard line on allowing anyone to access a machine’s fi rmware, and offers to work out repairs with users as needed .

Graphic courtesy of Deere

State-by-State Battles Over Repair Legislation

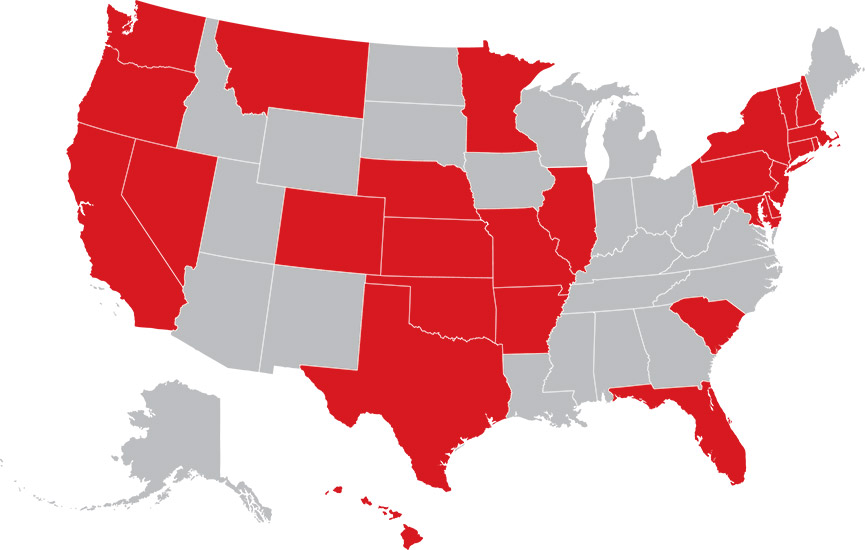

More than half of the state legislatures in the U.S. are considering some form of right to repair legislation. So far only one bill has advanced, passing the New York State Senate but not yet taken up by the state Assembly. Right to repair bills vary from state to state. Some target consumer electronics, farm equipment and other industries with broad language, while others are dialed in to address specific industries.

“It’s a crazy idea that someone should be locked out of fixing a thing they paid money for due to a restriction put in place by the manufacturer,” says Kevin O’Reilly, national director of the right to repair effort for U.S. Public Interest Research Groups (PIRG), a network of non-profit advocacy and activist organizations. “Software has become so instrumental to everything we use these days, from a John Deere tractor to a hospital ventilator.” O’Reilly explains that he and other right to repair advocates aren’t Luddites, they simply want to establish ground rules for access to devices and equipment that people have purchased. “New software is meant to help make a job easier, not help the manufacturer lock out devices when they break.”

PIRG and O’Reilly have spearheaded lobbying efforts to introduce right to repair bills at the state level. He notes these efforts aren’t meant to just address the problem state-by-state, but to create precedents that can lead to comprehensive changes by OEMs. One example cited by many repair advocates is an automotive right to repair act enacted in Massachusetts in 2012. Passed by ballot measure, it requires automakers to make the onboard data ports in on-road vehicles usable by independent repair shops. Rather than produce cars just for the Massachusetts market, major automakers have treated the requirement as a de facto national standard. Right to repair advocates hope that just one or two state laws could trigger a similar broad shift in OEM policies.

PIRG has taken up the cause of allowing independent repairs of farm equipment alongside its past campaigns for smartphone repair access.

Graphics courtesy of PIRG

Dealers Push Back Under Pressure

The right to repair battle isn’t just a showdown between repair advocates and OEMs. Most construction and farm equipment is purchased through dealers and resellers, with relatively few direct sales by OEMs. Dealer networks—the distributors who actually deal with the customers—have weighed in on the debate as well. The Equipment Dealers Association (EDA) and the Associated Equipment Distributors (AED) have both taken stands against right to repair legislation, saying proposed bills go too far in unlocking the software governing equipment.

“It just would not make sense to apply right to repair to the construction industry.”

—Stephanie See, director of government relations, Association of Equipment Manufacturers

“This right to repair issue is a confluence of many issues,” says Josh Evans, vice president for government relations and general counsel for EDA. “Just because you know what an error code on a machine means, you still need the background to repair it, and all of the service manuals don’t give you the expertise to do that.” Evans adds that OEMs such as Deere have begun to make diagnostic tools available, but training is still required.

Daniel Fisher, AED’s vice president of government and external affairs, says that while some consumer goods may need some new repair-related regulation, agricultural and construction equipment are a different beast. “We don’t view heavy equipment in the same realm. We’re getting lumped in a group of products that we don’t feel are in the same playing field really.” He adds that some dealers are concerned about servicing machines that may have already been modified to defeat emissions controls or safety features. Fisher says this could open them up to possible liability issues in the future. “Right now we view [right to repair] as a solution in search of a problem.”

27 state legislatures are currently considering bills that would codify some right to repair for electronics, farm equipment and other products with embedded digital systems. Industries affected vary by state.

Source: PIRG

Federal Action Upends Repair Debate

The regulatory battle over the right to repair had primarily been fought statehouse-by-statehouse until earlier this year. Recent actions taken by the Biden administration have shaken things up quite a bit.

In May, the Federal Trade Commission issued a report to congress on a right to repair investigation begun in 2017. The report, titled “Nixing the Fix,” examines many of the objections raised by OEMs over the repair of consumer electronics and other devices and equipment, and found them wanting. In particular, the FTC cited the precedent of the Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act of 1975, which forbids manufacturers from tying warranty coverage to customers’ use of OEM parts or services. Steering owners of devices and equipment to use only OEM-approved repair and service channels could be considered an anticompetitive practice in some circumstances, the FTC concluded.

“It’s a crazy idea that someone should be locked out of fixing a thing they paid money for due to a restriction put in place by the manufacturer.”

—Kevin O’Reilly, U.S. PIRG right to repair director

This report was followed by an executive order signed by President Biden on July 9, which called for federal agencies to address anticompetitive practices across many sectors of the economy. The order asks relevant federal agencies to examine existing repair and maintenance channels for signs of monopolies and anticompetitive practices. It also addresses the farm equipment issue directly. “[This order] encourages the FTC to limit powerful equipment manufacturers from restricting people’s ability to use independent repair shops or do DIY repairs—such as when tractor companies block farmers from repairing their own tractors,” stated a fact sheet published by the White House alongside the executive order.

The FTC followed shortly after with its own action, voting unanimously on July 21 to step up enforcement against illegal repair restrictions. These efforts will include examining practices by OEM-authorized servicers for possible antitrust violations.

“The very bright line between repair and modification is that repair is restoration, not modification,” says Gordon-Byrne. “The FTC felt that was a very important bright line to establish—if you can’t repair your stuff and bring it back to spec, that is a problem.”

While the FTC action is welcomed by repair advocates, there is as of yet no new right to repair rule or regulation proposed at the federal level. But supporters such as iFixit’s Wiens see it as welcome bit of momentum for their movement. “The Magnuson-Moss Act says clearly that manufacturers can’t condition a warranty on only them doing the service. That is unless they can prove that you did damage, but even then the burden of proof is on the manufacturer,” he says. “The FTC said in its latest report that if you see this behavior, it is fraud, and is asking people to report cases.”

“The FTC has said that it will support consumer complaints against manufacturers not allowing repairs, and we at the EDA support that,” says Evans. But he adds that having access and actually effecting repairs is different, and most owners in the agricultural space are not showing interest in buying the devices to access digital systems and make repairs. “Really, as a dealer network we are getting better at explaining to customers what can be done.”

“I don’t want to be in between the government and my customer—our goal at the end of the day is to keep their machines running,” says Adam Gilbertson, regional vice president at RDO Equipment Co. Gilbertson oversees RDO’s Midwest region and also serves as president of the Montana Equipment Dealers Association.

Construction equipment is often serviced under manufacturer warranty, but digital components can lock out independent repairs.

Photo by Jeff Rubenstone for ENR

He says that while OEMs such as Deere have made some diagnostic equipment available for independent servicing in recent years, there’s a lack of understanding among owners and operators about what’s out there. “If a sensor goes out or you need to regenerate an engine, or there is something to troubleshoot or calibrate, those diagnostic tools are available now. But in Montana, none of us have sold any of those tools yet.” Gilbertson says that shifts in regulation are only a part of the issue, and whether it’s construction or agriculture, contractors and farmers are not always aware of what’s available through existing repair and service channels. “It’s an opportunity for education.” He adds that Montana EDA is already looking to expand efforts to educate its customers about the kinds of repairs that can be performed without a dealer’s direct help, even if it means going in and resetting some software settings along the way.

“The thing is, if you have a mechanical problem that you can solve with a wrench or a hammer, you can probably figure it out yourself,” says PIRG’s O’Reilly. “But as you get into the computer stuff, there are a lot more barriers. It will require new skill sets to get through them.” But he adds that these are hurdles that can be cleared, and there’s no need to mystify computer-related repairs. “Whether you’re a consumer or a business, you need to be able to use a thing you purchased when you need to use it.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment