Dam engineers and safety experts say the drama that unfolded in February at California’s Oroville dam, when trouble with the main and emergency spillways led to the evacuation of tens of thousands of residents, could be a good thing for dam safety in the U.S.

“The Oroville event represents an opportunity,” says Martin McCann Jr., director of the National Performance of Dams Project and a civil engineering professor at Stanford University. “The dam didn’t fail. The spillway didn’t fail. No one got killed. So, let’s count our blessings and seize the opportunity.”

An expert panel of engineers this fall will present a forensics analysis to pinpoint the likely causes of the spillway failures. The more pressing concern is the lack of money to upgrade the 81,051 smaller, state-regulated dams, say dam engineers and officials.

In 2015, following a record rainfall, 51 of these smaller dams failed in South Carolina. Of the 90,000 dams in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ National Inventory of Dams, 58,000 are privately owned, and some, as in the state of Alabama, are not regulated at all. The Association of State Dam Safety Officials (ASDSO) estimates the cost exceeds $64 billion to rehabilitate the nation’s non-federal and federal dams.

The combination of these factors—not just the threat of big dams such as Oroville—led the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) to give dams a D grade in its latest report card. “We watch our federal dams really well,” says Dusty Myers, president of the ASDSO and chief of Mississippi’s dam program. “Our states are really stressed.”

Dam engineering and regulation has come far since the 1970s, when a series of failures killed dozens of people and caused billions of dollars in damage. Subsequent reviews showed that dam safety laws and regulations were inadequate. In response to those reviews, ASDSO was created in 1984.

Oversight is “definitely stronger,” says Mark Ogden, a technical specialist at ASDSO who helped to write ASCE’s dam report card. “Some states didn’t have a program back then.” Since about 2010, ASDSO has put a new focus on learning lessons from previous dam failures. Along with the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the group has created damfailures.org to share information about past failures. They expect that the Oroville case will yield a wealth of new information.

“You want to know the physical cause of the problem” but also what human factors may have contributed, says Mark Baker, chairman of ASDSO’s dam-failure committee.

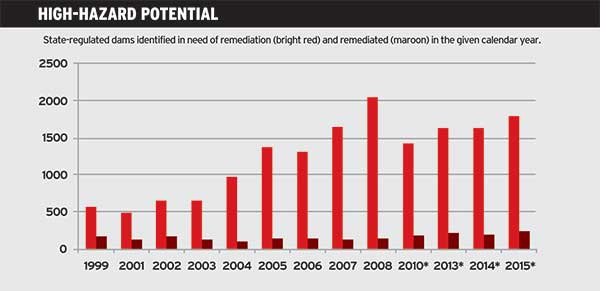

Even as improvements have been made, dams are posing an increasing risk because they are getting older—in the U.S., the average age is 56, and about 4,400 are more than 100 years old. Further, the dams were not built to today’s seismic standards, and real-life storms and new storm models show many dams are inadequate to handle heavy rainfall. Dam owners’ responsibility for public safety has expanded with the growing number of people building and living in the dam-failure flood path. In the national inventory, the number of dams considered “high hazard,” or exhibiting the potential for fatalities after a failure, has grown to 15,500 in 2017 from 10,213 in 2005.

“It’s not because we are doing anything wrong,” says Bob Beduhn, director of dams and levees for HDR. “It’s that we are allowing people to live within the flood plain of the dam.” Beduhn adds that there’s a disconnect in the national flood insurance program, which doesn’t necessarily require flood insurance in dam flood plains.

To tackle the ever-increasing number of dams that need work, federal agencies, utilities and a growing number of states are turning to a risk-based approach to analyze and address problems at the nation’s dams. “It would be impossible to rehabilitate all the dams at once,” says Roger Adams, chief of dam safety for Pennsylvania.

By employing a risk-based approach to its 700 dams, the Corps of Engineers has avoided $7 billion of work, says Eric Halpin, deputy for dam and levee safety for the Corps. “We couldn’t afford not to do it,” he says.

Major work is ongoing at several dams, including the Corps’ Isabella Dam in California, which was created in the 1950s in a remote area of the state, but now puts more than 300,000 people downstream in Bakersfield at risk. A risk analysis determined the dam needed seismic updates, had seepage issues and could be overtopped.

Other federal agencies, including the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which regulates the Oroville Dam, are currently incorporating risk-based practices.

States and individual owners have been slower to adopt a risk-based approach because of costs and resistance from owners.

The cost issue may be a red herring. Dan Wade, director of the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission’s water improvement program, says the risk-based analysis doesn’t need to be expensive or complicated. Where a large dam might have a 100-page risk-management plan, a small dam may need a three- to five-page plan. “It needs to fit the project,” Wade says. “We need to get past the concerns about cost.”

Funding Shortfalls

However, after the problems have been identified, the biggest problem of all—funding—comes next. “We can issue orders, but what happens if they can’t come up with the funding, especially on private dams? Those are the biggest struggles,” says Jon Garton, who manages the dam safety program in Iowa. Only about half the states have some type of low-interest loan program to help pay for rehabilitation.

The Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation bill, signed into law last year, established a $445-million fund to remediate high-hazard dams, but Congress has yet to appropriate any money for the fund. “The only way that work is going to uptick is if funding is provided some way,” says Craig Harris, western water division director for MWH, a unit of Stantec.

That’s not to say that work isn’t occurring. Communities that use their dams for water and recreation, utilities and states are spending billions to upgrade and maintain their dams.

“Many communities consider their dams forever after and spend a lot of money to make sure they are operated safely,” said Mike Manwaring, business development director for Stantec’s water and dam division

For the past decade or more, new seismic modeling has driven much of the dam work. Even before Oroville, there was a great emphasis on spillway work. Most dams and spillways were built based on old weather data. Now, more recent information shows that dams don’t have adequate capacity for downpours or their spillways are undersized.

Adding Resilience

While it may be impossible to build all dams to withstand the 1,000-year event that occurred in South Carolina in 2015, dams can be built to be more resilient, says Hermann Fritz, a Georgia Tech civil engineering professor who led the Geotechnical Extreme Events Reconnaissance team that analyzed the South Carolina dam failures. For the most part, South Carolina provided a model for what is not being done in dam management, design and operations. For example, Fritz says, there were old, unknown materials that created seams and points of failure in dams. Turbines couldn’t be operated because power failed; gates had to be opened manually in the deluge; spillways weren’t designed properly; stop logs, meant to be removed in the event of a storm, had been cemented in.

“It showed all of the challenges of operation of these smaller dams,” he said.

In the end, the international team that has come together to analyze and learn the lessons from Oroville represents the path forward for national dam safety and the mind-set that supports it.

Says James Demby, senior technical policy adviser for FEMA’s National Dam Safety Program, “Dam safety is really a shared responsibility.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment