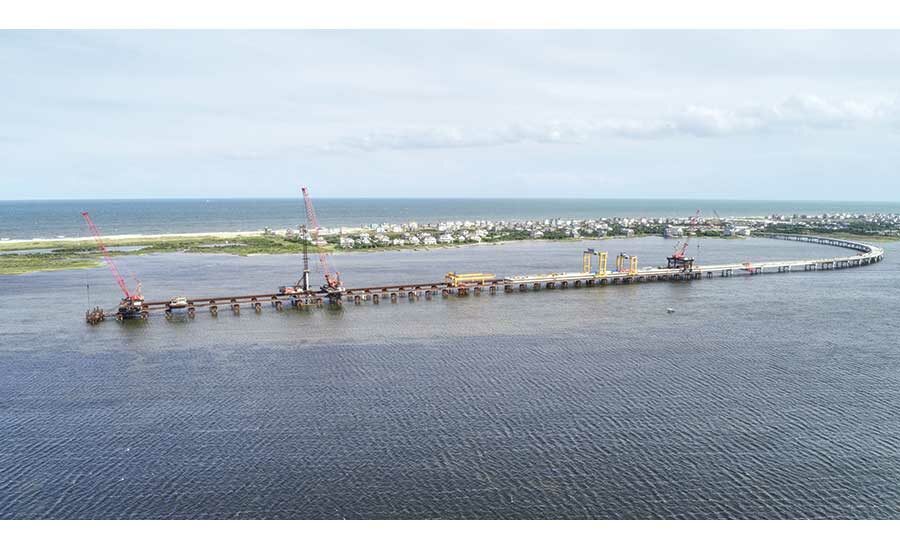

From atop the gantries being used to erect the Rodanthe Bridge in North Carolina’s Pamlico Sound, a worker can look across the sands of windswept Hatteras Island and see Atlantic Ocean waves pounding the shoreline next to the two-lane State Route 12, the sole road connecting a chain of tourism-dependent villages to the mainland. The view is a reminder of why the North Carolina Dept. of Transportation is spending $145 million to build the 2.4-mile-long elevated road.

The bridge will bypass an area of Route 12 called the S Curves, which in 2011 required a $3-million emergency repair effort to fill and cover a temporary inlet created by Hurricane Irene, and a $20-million U.S. Army Corps of Engineers-funded beach nourishment project the following year. NCDOT monitoring data shows the S Curves’ oceanfront is being eaten away at a rate of 11 ft to 12 ft per year. Forecasts for 2060 indicate that even under low-erosion scenarios, other sections of the 12.5-mile corridor will be similarly vulnerable to encroachment.

NCDOT is not alone in facing the need to adapt coast-hugging infrastructure to a changing environment. According to the US Global Change Research Program’s Fourth National Climate Assessment, global sea levels could rise 1 ft to 4 ft during the 21st century. But while most areas with at-risk infrastructure are aware that adaptation and, in extreme cases, retreat from the shoreline, may be an inescapable outcome, few such projects are actually underway. The reason is not always as simple as lack of funding.

“You can’t just pick up a road and move it,” says Annie Bennett, a senior associate with the Washington, D.C.-based Georgetown Climate Center. “It points to the importance of planning and integrated decision-making.” Even with that, Bennett adds, the process can be complicated and fraught with political pushback, as localities and governing agencies wrestle with issues such as land use and acquisition, public safety and environmental mitigation. Efforts to achieve consensus on infrastructure relocation have been aided in recent years by improvements in data collection that narrow global-scale climate trends down to specific, close-to-home impacts. “It’s a matter of making the case in a way that resonates locally, and gets the conversations started,” Bennett says.

For NCDOT, the impetus for the Rodanthe Bridge was a 2015 legal settlement with environmental groups that cleared the way for a new bridge across Oregon Inlet, located at the north end of the vulnerable corridor that also contains the Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge. To guide highway management, the agency monitors erosion patterns using a combination of color and near-infrared aerial photography, digital terrain models, storm data and other inputs. According to NCDOT project manager John Conforti, areas of primary concern are where island width has shrunk to less than 1,000 ft, dune crest elevation is less than 10 ft above the Route 12 centerline, and the shore is less than 230 ft from the pavement. The S Curves meets all three criteria, he adds.

Migration patterns would leave parts of Route 12’s existing alignment in the ocean surf by mid-century, so NCDOT elected to bypass the S Curves with a bridge, being built by Flatiron Construction Co., that can be adapted or extended should other sections of the Pea Island corridor require relocation in the future.

NCDOT is utilizing other resiliency measures along the coast to safeguard its infrastructure, including building 2,500 ft of living shorelines to protect a section of State Route 24, a key storm evacuation route that also serves the Camp LeJeune Marine Corps base and a local community college. Conforti says that the $2.6-million project, partially funded by a grant from the NOAA/National Fish and Wildlife Foundation Emergency Coastal Resilience Fund, “is the first proof-of-concept using nature-based design in its efforts to make coastal roads more resilient to storms.”

West Coast Encroachments

On the other side of the continent, rising sea levels and intensified storm surges from changing weather patterns are gradually undermining headlands and bluffs that support critical infrastructure such as California’s State Highway 1, which, like North Carolina’s Route 12, links hundreds of coastal and inland communities.

Closures and repairs due to mudslides, erosion and flooding along Highway 1 have become more frequent in recent years. At Gleason Beach in Sonoma County, for example, a Caltrans study found that the 70-ft-high bluffs supporting the highway are being undermined by 1 ft of erosion and bluff retreat annually, a rate that could increase by another ½-ft or more by 2050.

Caltrans recently received the California Coastal Commission’s approval for a $73-million project that will relocate a 3,700-ft-long section of the two-lane highway approximately 400 ft inland, providing what the agency hopes is at least a century’s worth of protection from continued erosion. Land acquisition is currently underway for the project, which is expected to begin in 2023, and will include an 850-ft-long bridge to allow natural expansion of a creek and floodplain.

Down the coast, the San Diego Association of Governments and North County Transit District are wrapping up the fourth phase of a long-term program to stabilize a 1.7-mile section of the 40-ft-high Del Mar bluffs, on which is located a single-track rail line that is an integral part of the nation’s second-busiest intercity passenger railroad corridor.

Launched in 2003, the stabilization program has included installation of reinforced support piles up to 60 ft deep with diameters ranging from 36 in. to 42 in., as well as seismic and drainage infrastructure upgrades and retrofits to 640 ft of seawall.

John Haggerty, SANDAG Director of Engineering and Construction, says that while historical data suggests an annual erosion rate of 6 in., episodic events such as a November 2019 storm event that eroded already stabilized sections of the bluffs by as much as 10 ft and cost $40 million to repair are a reminder that nature may be on a different timeline.

“Sea level rise hasn’t been overly significant yet, but we do see it as a potential threat in the coming decades,” Haggerty says, “particularly in winter when large waves wash up to the base of the bluff.”

The program’s remaining two phases, estimated to cost $110 million and set for implementation over the next several years, should be enough to stabilize the bluffs for another 30 years, Haggerty says, allowing agencies to focus on the eventual relocation of the tracks off the bluffs entirely. Almost all of the conceptual alignment alternatives call for excavating a tunnel below Del Mar, with unofficial construction estimates ranging upwards of $3 billion.“For now, we feel like we’re getting ahead of the risks,” Haggerty says.

Racing the Clock—and the Climate

Even with well-developed coastal infrastructure adaptation plans, funding is most communities’ biggest challenge. In Florida, where sea levels are forecast to rise faster than the global average over the next 20 years, several cities have been successful in making the case for resiliency programs. The most recent is the Village of Key Biscayne, where in November voters approved a $100-million bond issue to fund measures, including $40 million for a complete streets approach, to mitigate flood risks.

Further from the mainland, however, infrastructure vulnerability to sea level rise is increasing, as are the costs of addressing it. Monroe County, which includes the Florida Keys, has seen an upward trend in seasonal king tides—high tides generally related to moon phases—over the past decade, from an average of two to three annual occurrences in 2010 to an estimated 20 such events this year. “The spring and fall king tide events we see now are preview of what we’ll see year-round in 20 to 25 years,” says Rhonda Haag, the county’s sustainability projects director.

Indeed, estimates based on data from one tide gauge point to 1-ft “nuisance flood” conditions occurring as often as twice daily under a worst-case scenario. Yet raising just the most vulnerable of the county’s 314 miles of roads would carry average per-mile costs ranging up to $2.5 million, according to county estimates. Appeals to the state government for additional resiliency-targeted funding have been unsuccessful.

As an interim measure, the county has installed temporary flood control barriers along roads in two vulnerable Key Largo neighborhoods. Because the areas suffer from near-constant flooding, Haag says, the barriers may soon remain deployed between king tide events.

Monroe County hopes to identify other priority areas through an HDR-led $1.8-million road elevation study, due for completion next summer. Haag adds that design is nearly complete on two pilot projects for road and stormwater improvements that would provide a model for addressing flood impacts elsewhere in the county, but funds to cover the estimated $14-million construction cost have yet to be identified. “We’ve applied to some federal grant programs,” Haag says, “and are just hoping for some good news.”