Cities, states and regions are taking steps to prepare their buildings, infrastructure and homes for the impacts of climate change as bad news continues to mount about rising sea levels.

A June 18 report from the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) used National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration sea-level rise scenarios and Zillow real estate data. The report found that within 15 years, about 147,000 existing homes and 7,000 commercial properties, worth $63 billion, could flood once every other week. Within 30 years, that number will double. By the end of the century, as many as 2.4 million homes and 107,000 commercial properties will chronically flood.

“We should recognize coastal flood risk for the predictable, slow-moving disaster that it is, rather than respond only episodically, i.e., in the aftermath of major storms,” UCS concludes, recommending the federal government reduce the risk by spending more money before storms to make communities more resilient.

Some governments are taking heed. In May, the Connecticut legislature passed a law requiring all federal or state-funded projects to take sea-level rise into account. In June, Hawaii Gov. David Ige (D) signed a bill requiring analysis of sea-level rise in environmental impact statements. In Virginia, Gov. Ralph Northam (D) on June 22 signed a bill to create a new cabinet position to address coastal adaptation and protection.

Also in June, the Boston Planning and Development Agency approved a two-year “smart utilities” pilot program that includes a requirement for large developments to study the possibility of district energy microgrids and incorporate more green infrastructure.

The policy, the first of its kind in the United States, will help prepare Boston for the future impacts of climate change, according to the agency. A quarter of Boston would be underwater by 2100 under a high sea-level rise scenario, according to the UCS study.

Repeat record floods and storms in Boston prepped the public to accept the changes. “Everyone in the infrastructure world … has been thinking about this for decades,” says Tad Read, a senior deputy director with the department. “The storms make it clear that this policy makes sense, and it’s obvious that this is the right time to do something.”

Acting on sea-level rise is proving to be more difficult in the San Francisco Bay area, which hasn’t experienced flooding at the same level. Yet, through the yearlong Resilient by Design Challenge, which wrapped up in May, the area is attempting to act before it’s too late. The challenge, modeled after New York’s Rebuild by Design challenge, resulted in nine final plans to help make the area more resilient and less vulnerable to sea-level rise.

The proposals are ambitious in scope and have community buy-in, but unlike in Rebuild by Design, there is no federal money to put the plans into action.

The challenge is, in part, a test to see if pre-disaster concepts can be put in place without a disaster and without a big pool of funding, says Zoe Siegel, program manager for the challenge.

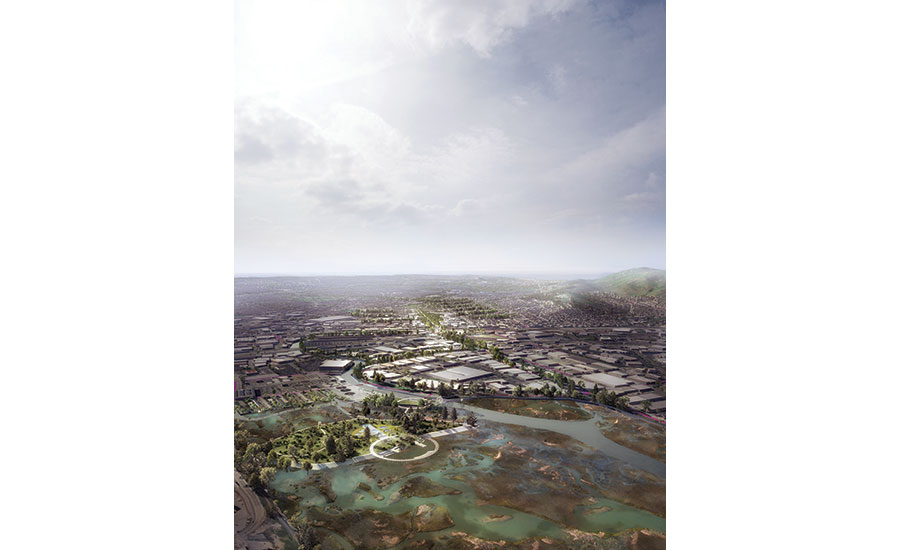

“We are still in the early stages of people really taking it on as a problem,” says Rosey Jencks of Brown and Caldwell, which worked on a San Mateo plan led by architects at HASSELL. The concept focused on creating floodable spaces and making sure floods don’t cascade and cause upstream flooding.

Another proposal, led by SCAPE Landscape Architecture with Arcadis engineers, would use sediment from Alameda Creek to help keep the region’s marshes intact as sea level is expected to rise 3.5 ft by 2100.

The group is planning to continue to work together and will seek funding and financing options, says Chris Devick, project manager at Arcadis. While the endpoint is still unclear, Devick says the challenge “was a fantastic way to create an open discussion” that created a broad consensus about solutions.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment