The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and levee districts throughout Mississippi River Watershed are preparing for potentially imminent floods by drawing on a battery of strategies, the first of which is keeping a close watch on weather patterns, water levels and soil conditions.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and levee districts throughout Mississippi River Watershed are preparing for potentially imminent floods by drawing on a battery of strategies, the first of which is keeping a close watch on weather patterns, water levels and soil conditions.

“We are monitoring National Weather Service forecasts for snow pack, saturation, snow melt and rain,” says Brig. Gen. Michael Walsh, commander of the Corps’ Mississippi Valley Division and president-designee of the Mississippi River Commission. “Our teams are prepared.”

Unusually high precipitation since the fall throughout the Mississippi River & Tributaries system has resulted in high water levels earlier than usual. Typically, the high-water season begins in April or May. As a result, “the flood-fight,” as the Corps calls it, which draws on a set of standard, but localized protocols, already is under way.

New Orleans has been in the fight since last fall. Average river level at the city is +6.7 ft. The Phase-1 flood fight there begins when the Carrollton gauge on the Mississippi River reaches +11 ft and is rising.

“We reached a maximum height of +15.55 ft at the Carrollton gauge Nov. 10, which was a record for that time of year,” says Mike Stack, chief of emergency management for the Corps’ New Orleans District.

He explained that the Nov. 10 level was a spike caused by a hit from a tropical storm, but even before and after the spike the river height was 13.5 ft, which still would have been a record for that time of year. “In December, we reached +14.9 ft at the Carrollton gauge,” says Stack.

“In Phase I we ride the levees twice a week, look them over, inspect for changes in the system, including wet spots on the protected side, seepage, sand boils and slides,” Stack adds.

Slides occurr when part of the levee slope peels away, usually from heavy rain on dry material. Slide repairs require some surface re-compaction.

Sand boils—where water wells up out of the ground on the protected side like a spring, sometimes building a sediment fan—are monitored to make sure the water has a clear flow, which relieves pressure without removing internal material in a way that could undermine the structure.

Sandbag rings and relief wells may be installed where the water emerges to raise the inside head to slow the velocity and reduce erosion, protect the levees and relieve pressure.

The New Orleans District moves up to daily inspections in Phase II, when the Carrollton gauge is at +15 ft and rising.

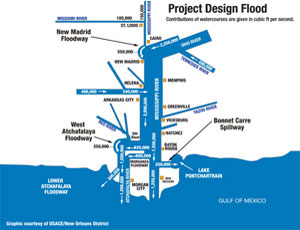

That’s also when the river has a flow of 1.25 million cubic feet per second, which is the trigger for opening the Bonnet Carre´ Spillway above New Orleans to reduce velocity and volume of the torrent pouring past the levees of the city. The Bonnet Carre´ last was opened in 2008, and prior to that, in 1997.

When the Carrollton gauge reaches +17 ft and is rising, levee inspections are performed 24 hours a day. When the river reaches 1.5 million cfs at New Orleans, that triggers the opening of another river control structure, the Morganza Spillway. The Morganza has only been opened once, in 1973, since it was completed 55 years ago.

Flood prospects have officials watching the situation closely now all up the MR&T system. Unusually high water levels and seepage spots also have been challenging the Vicksburg (Miss.) District levees since last fall, says Wayland Hill, senior technician in the hydraulics branch of the water control management section in the Corps’ Vicksburg District.

The trigger for a Phase-I fight in Vicksburg is +44 ft at the Vicksburg gauge. “The Vicksburg gauge has been up to +41 ft so far this winter,” Hill says, but the district has been engaged in flood fight activities based on local conditions since last fall. Phase II is triggered by a +49 ft reading at the gauge and includes 24-hour monitoring.

The average annual water level at Vicksburg is +21 ft. In 2008 it peaked at +51 ft, Hill says.

Assessing the big picture, Stack says there has been a succession of heavy rain events for months throughout the Mississippi River watershed, which starts at the headwater in Minnesota and drains 41% of the country.

Now, with spring drawing near, heavy snowpack north of St. Louis and on the Ohio, Illinois and Missouri Rivers is raising concern, with snow water equivalents expected to add from 1 in. to 5 in. of water in those areas, says Bill Frederick, head meteorologist at the NWS office in Vicksburg and liaison between the NWS and the Corps’ Mississippi Valley Division.

The NWS’ Advanced Hydrologic Prediction System, which predicts river levels three months in advance, indicates that all systems north of St. Louis are at “above-normal risk for flooding and some areas are much above normal,” Frederick says. The big determinant is how the snow pack melts.

Adding anxiety to this year’s preparations, flood watchers worry that anticipated heavy spring rains associated with an El Nino weather pattern now in place may have a cascading effect if the rain falls on snowpacks and still-frozen, saturated ground. That would mean any new precipitation immediately would drain into the rivers, says Frederick, adding that the NWS is predicting continued, colder temperatures, which is another bad sign.

“If we continue to have colder temperatures up north, we’ll get into the rainier part of the season and have melt off.” If temperatures rise and hard rains melt the snow rapidly, problems will be compounded.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment