As the inventory of existing buildings continues to grow in the U.S., leaders in the historic preservation community are sounding the alarm that the construction industry is in dire need of workers with historic trades training. Recent studies suggest that thousands of trade people with training in historic trades—such as masons, plasterers and carpenters—will need to enter the workforce each year to keep up with demand. In response, advocates are pushing to expand training opportunities and create registered apprenticeships in the historic trades that are recognized nationwide.

Last year, the American Institute of Architects reported that billings for rehabilitation work exceeded new construction for the first time in 20 years of tracking. Historic trades make up an estimated 12.6% of all building rehabilitation projects, according to an analysis released in November 2022 by The Campaign for Historic Trades. More than 40% of all U.S. buildings were built at least 50 years ago, making them potentially eligible for historic designation, according to the report. An additional 13.3 million buildings could reach the 50-year mark in the next decade.

An interest in architecture and working with his hands led Phil Aguiar to pursue a career in historic trades.

Photo by Bruce Buckley

“We are not niche,” says Nicholas Redding, executive director of Preservation Maryland, which is part of The Campaign for Historic Trades, along with the U.S. National Park Service’s Historic Preservation Training Center. “There is a misperception that this touches only a handful of buildings. There’s a huge need associated with this kind of work.”

The report estimates historic rehabilitation work creates 165,000 jobs each year, and 60% of jobs demand preservation skills. In his own state, Redding notes during last year’s restoration of the Maryland State House Dome, experts in historic linseed oil painting were brought in from Michigan because no local contractors had the capacity and skills needed. “That meant paying to bring them in, put them up in hotels and give them per diems,” he says.

Woodworking hand tools at the U.S. National Park Service’s Historic Preservation Training Center in Frederick, Md.

Photo by Bruce Buckley

Redding estimates that to keep up with demand nationwide, 10,000 workers with training in historic trades will need to be added to the workforce annually. “When you account for attrition, it could require more than 15,000 people annually just to hold the line,” he adds.

Moss Rudley, superintendent of the National Park Service’s Historic Preservation Training Center in Frederick, Md., says when the Parks Service plans rehabilitation projects, it often estimates a 50% escalation factor to account for unknown conditions, materials costs and specialized labor. To help address the issue, NPS has leaned on the HPTC for decades to train its in-house maintenance staff. About 50 interns enter the program every year.

Clamps used for restoration work at the Historic Preservation Training Center.

Photo by Bruce Buckley

Crews with specialized training can be deployed around the country, spending up to 40 weeks per year at various parks. To support its efforts, the program has been expanded to 15 locations around the country.

The program has received a boost from recent legislation—including the Great American Outdoors Act of 2020, which provides funding to improve infrastructure in national parks—as well as provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. In the last two years, the organization has grown from 75 people to more than 150. Over the next three to five years, Rudley says the organization could grow to a staff of 400. HPTC’s established track record in training workers has proven critical in The Campaign for Historic Trades’ mission to expand training opportunities at the state and local levels and establish registered apprenticeships.

Redding says the campaign is focused on creating registered apprenticeships so they can be recognized by federal and state entities. Getting these registered apprenticeships recognized by the U.S. Dept. of Labor would “unlock” federal and state funding, he says.

“Maryland, for example, is one of the states that automatically accepts what the Dept. of Labor recognizes,” he says. “Community colleges in the state would then be able to tap into funding to help establish these programs.” Redding says he expects some historic trades apprenticeships to be registered this year, possibly as early as this summer.

Jack McCorrison, maintenance worker with the HPTC, sands a historic window at the Frederick, Md., facility.

Photo by Bruce Buckley

Given that construction unions have their own apprenticeship programs, Rudley says he has had ongoing discussions with unions. “For years, I taught a historic preservation module for the International Masonry Institute, which is the educational side of the Bricklayers and Allied Craftworkers,” he says. “We are not in competition with any unions or union contractors. We’re getting close to actually signing a cooperative agreement with the bricklayers [union].”

To help colleges and other institutions start training programs, The Campaign for Historic Trades works with partners to create open-source curriculum to be offered for free. “If you want to take it off the shelf and rapidly deploy it, then you’re ready to roll,” he says.

Establishing historic trades training programs at colleges and other institutions could prove a monumental task. Dave Mertz, who established the Building and Preservation Program at Belmont College in St. Clairsville, Ohio, says while there are a handful of well-established programs at U.S. colleges, many have come and gone over the years. In most cases, he says, a “champion” comes in and establishes a historic trades program, but once that person leaves the position, no one is able to step in. “It’s hard enough to find someone who has the technical background and knows how to teach,” he says. “They also need to play the game and show the administration the program is valuable.”

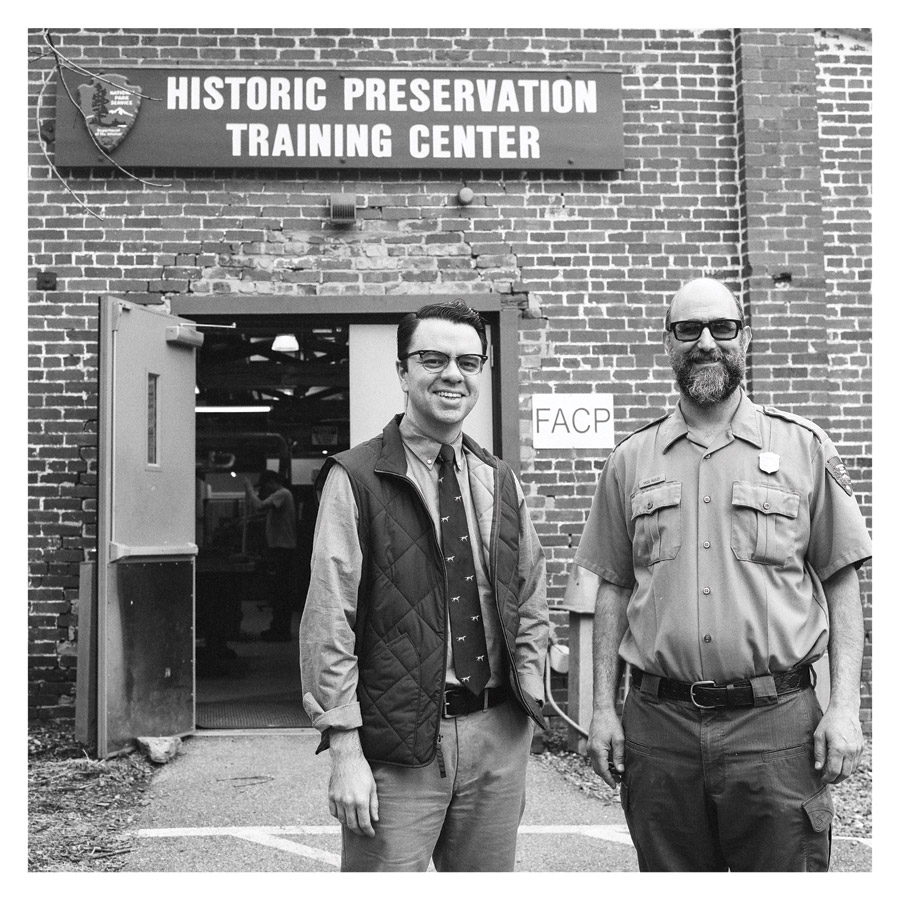

Nicholas Redding, left, executive director of Preservation Maryland, with Moss Rudley, superintendent at the HPTC

Photo by Bruce Buckley

In San Antonio, the city pursued establishing historic trades programs at schools as a way to meet rising demand, but ultimately chose to create its own program. “It was just taking longer than we wanted, so we did it ourselves,” says Shannon Shea Miller, historic preservation director with the city’s Office of Historic Preservation.

The program offers students a week-long training course with a master craftsman followed by a 10-week paid apprenticeship with a contractor. As a program that doesn’t require a two-year commitment, Miller says the program draws a broad range of students.

Miller says that many successful students share a common interest in working on projects that aren’t “cookie cutter” and repetitive like some modern production techniques. “No historic building is alike, and I think [historic trades programs] work better if students recognize that and appreciate that,” she says. “It requires being more thoughtful about how to go about addressing a problem.”

Phil Aguiar, a maintenance worker at the National Parks Service and former HPTC intern, says he was drawn to the historic trades because of an interest in architecture and working with his hands. He enrolled in the program at Belmont College, which led to a position with NPS.

“I’m working in the wood crafting section here, and there’s just so much to learn,” he says. “But that’s what I love about it. I’m learning every day. I’ll probably never stop learning.”

For this feature story on historic restoration, ENR correspondent Bruce Buckley thought it appropriate to use a camera that had itself been fully restored—his 1974 Hasselblad 500C/M medium-format camera. The Hasselblad 500C/M line was introduced in 1970, says Buckley, and was used extensively for commercial and editorial projects throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Its predecessor, the 500C, was used by NASA to document space missions during the 1960s, including the moon landing in 1969. “I frame images by looking down at a large piece of ground glass on the top of the camera. It has an almost 3D look to it that makes shooting with the 500C/M an immersive experience.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment