In what’s left of Antakya, a once-thriving and cosmopolitan tourist destination in the southeastern edge of Turkey, the streets seem weirdly quiet. Buildings stand askew at odd angles or are completely toppled, and the rubble from the homes of people who lived inside of them is neatly collected into piles and mounds.

These piles of trash, a strange amalgamation of concrete and wire, shards of glass and blankets, toys and other small remnants of lives interrupted, seem to outnumber intact structures here in Antakya, the epicenter of a string of earthquakes that began with a 7.8-magnitude temblor on Feb. 6.

The impact on human life is unquestioned, but numerous sources suggest that a combination of governmental reforms that didn’t work, corruption and lax enforcement of existing building codes, as well as poor construction practices in many building projects created a perfect storm that made the situation much worse.

“The whole system is responsible for the outcome of this disaster,” said Mehmet Akdogan, director of Miyamoto Protek, a joint venture between Ankara -based Protek-Yapi, where Akdogan is CEO, and U.S.-based Miyamoto International. The two international firms are teaming to provide engineering expertise in response to the disaster.

The Turkish government has vowed to hold accountable those who are responsible, and more than 200 people—mainly contractors or building owners—have been arrested.

Turkey’s emergency management agency, AFAD, estimates that more than 50,000 people died as a result of the earthquakes in Turkey alone, although many news outlets contend that the actual number is likely much higher.

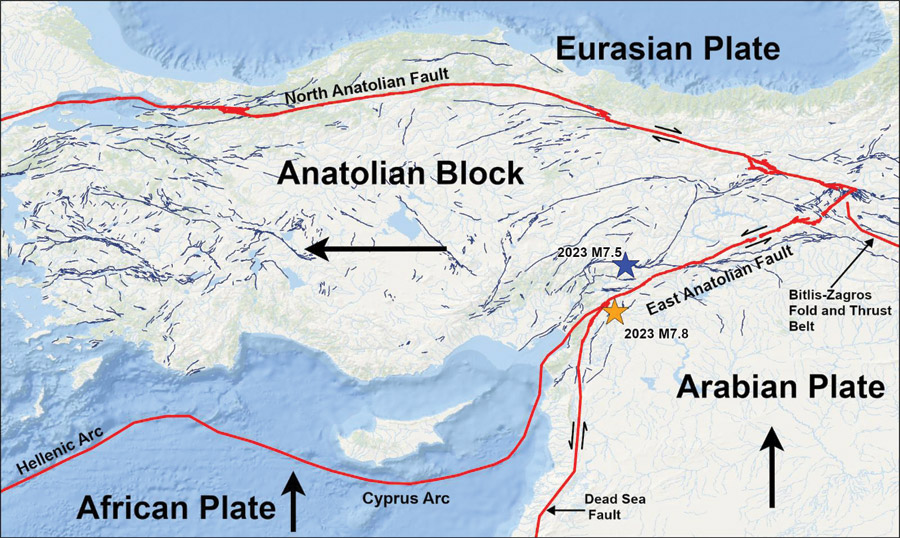

The World Bank’s latest Global Rapid Post-Disaster Estimation (GRADE) report released in late February says that the two largest earthquakes on Feb. 6—one a 7.8 magnitude quake, the other a 7.5-magnitude quake nine hours later—followed by more than 7,000 aftershocks and two additional earthquakes, caused an estimated $34.2 billion in direct physical damages across 11 provinces in Turkey, and more than $5 billion in Syria.

Turkey and Syria rest in a region historically prone to earthquakes. Many fear and are preparing for a potentially large quake in Istanbul sometime in the coming years.

Map courtesy of USGS

More than one million people have been rendered temporarily homeless. Many have left the region to stay with family of friends, while others have are staying in temporary tents and trailers provided by local governments, international organizations, and local construction firms.

AFAD itself donated more than 300,000 structures. In early March, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said the government would provide financial assistance to help people without homes to relocate.

Limak Construction mobilized 800 workers to assist with rescue efforts in the days following the earthquakes, including 150 Limak employees who were directly affected, says Ebru Ozdemir, the firm's chairwoman. “This was a really big tragedy for Turkey,” she says, adding that it was important to be able to ensure that all firm employees were safe. Limak has also joined other large Turkish construction companies as part of a committee to work in concert with local governments to build and deliver individual container homes and container “cities.”

Antakya, the historic capital city of Hatay province, seems to have been hardest-hit by the earthquakes, but several towns along the Turkish Mediterranean coast also have been affected.

Ozdemir says construction firms need to be able to build more sustainably. Citing major infrastructure projects not affected by the earthquakes, she notes that building to current standards can, and has been, done in Turkey. “We need to build back better because these cities need to be rebuilt, and they need to be built responsibly.”

Some of the worst damage is in Hatay Province. Antakya, historically called Antioch, was largely destroyed.

Photo by Pam McFarland/ENR

Assessing the Damage

The recovery effort is ongoing. Within days of the first two temblors, construction crews and rescue teams arrived to pull people from the rubble, and to tear down buildings on the verge of collapse. Thousands of international and local damage assessment teams fanned across affected cities in Turkey and Syria.

Mustafa Kizil, a senior engineer at Miyamoto Protek, who has performed assessments as part of a two-person team, says the devastation to buildings—many of them new or part of luxury developments—was caused by a multiplicity of factors.

Some were built on soft or alluvial soils with insufficient piling for support. When the ground began to shake during the earthquakes, soil liquefaction occurred and foundations crumbled or detached from the higher levels. Other structures had been built quickly, with cheap materials or processes that wouldn’t meet current building codes, he says.

Assessment teams performed visual analyses in the days and weeks after the first earthquakes, categorizing buildings into one of five categories: no damage, mild, moderate, highly damaged, and needing immediate demolition. Buildings with mild damage can be repaired over the next year, Kizil says, but anything categorized as moderate or worse will be demolished.

Since Erdoğan’s AK party came into power in 2002, Turkey has seen an enormous surge in construction projects. But many non-profits such as CHD – the Progressive Lawyers Association in Turkey, as well as local engineering chambers and seismic experts, blame lax enforcement of building codes as a major cause of the extent of the destruction from the earthquakes. Members of CHD have been visiting building sites, trying to find evidence of shoddy work, Kizil says.

Some cities, such as Osmaniye, are rebounding fairly quickly. But others, like Antakya, will take years to rebuild.

Photo courtesy of Miyamoto International

Esungül Kiran, a CHD member, says that lawyers from her group try to educate earthquake victims about their legal rights. She says that some people trying to retrieve furniture from their homes have been arrested or faced other charges. “The state must provide living spaces worthy of human dignity." she said in an email to ENR. "Until this is achieved, CHD will continue to advocate for the people in future violations.”

Miyamoto Protek’s Akdogan says building codes in Turkey have been updated several times, most recently in 2007 and 2019, and that—on paper at least—they are consistent with seismic standards around the world. Akdogan says the 2019 codes incorporated many elements of the American Society of Civil Engineers’ 7-16 seismic standard.

Turkey has a system in place for inspecting public buildings. But in 2011, the inspection system for private buildings and developments was largely privatized. “The problem is: the landowner see this as kind of extra money that he can make … so he tries to find ways out, to negotiate,” Akdogan says.

Additionally, prior to the 2018 elections, Erdoğan granted amnesty to owners of buildings that were built prior to the most recent code update at the time to allow more time for them to be brought up to required standards. Owners were required to apply for a registry that identified problems. According to Turkish newspaper Sözcü, more than three million building registry certificates were given throughout Turkey prior to the 2018 presidential elections.

Akdogan adds that almost anyone could claim to be a contractor prior to 2020. “Anyone, any company who wanted to build a building, could,” he says.

– By Pam McFarland in Hatay Province, Turkey.

_ENRready.jpg?height=200&t=1686916833&width=200)