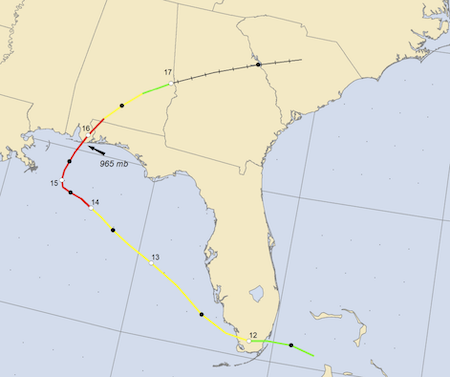

On Sept 15, 2020, a strong tropical storm neared the Gulf Coast of Florida and appeared to be heading for a landfall in Alabama. In Florida’s westernmost city, Pensacola, contractor Skanska had partly finished, and traffic was flowing over, the new 3-mile-long Pensacola Bay Bridge. Project leaders believed the worst could be avoided as the storm track called for it to land 200 miles away.

Fifty-five construction barges were tied down but most were left in the jobsite area.

Unexpectedly, the storm veered to the northeast and intensified—eventually becoming Hurricane Sally—coming ashore near Gulf Shores, Ala., only 30 miles west of the project site. Punished by wind and surge, 27 barges broke free of moorings, with several washing ashore on private property.

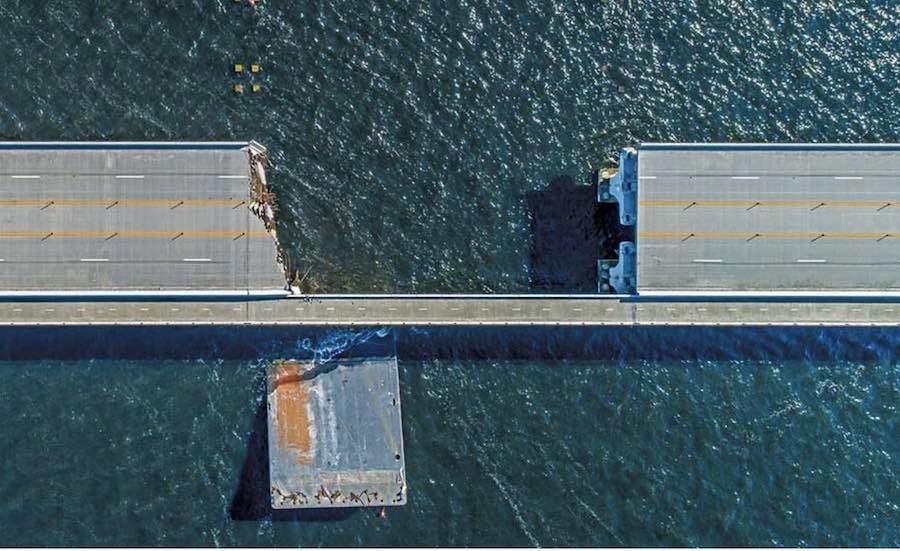

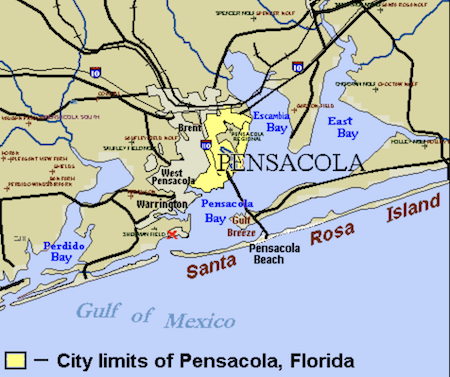

The wind, waves and storm surge drove one 120-ft-long barge into the new bridge, taking a bite out of its deck section and damaging many beams. Because the old bridge was already being demolished, it could not be re-opened to traffic, cutting off many local residents from quick access to the other side of the bay. After months of extensive repairs—and millions of dollars in added costs—the bridge reopened in June.

The overall cost to Skanska is still being tallied and includes penalties due to the Florida Dept. of Transportation for the bridge closure. But a four-day civil court trial of about 1,000 claims against the contractor by motorists and business and property owners concluded Oct. 22 in federal court in Pensacola. The decision could add millions to Skanska's total liability.

The court record shows that during pretrial maneuvering in the days leading up to the trial, the main issue—whether Skanska’s team was prudent in leaving the barges in place, or negligent, and how members came to their decision—was being examined in minute detail.

The case was initiated in 2020 by Skanska, seeking protection against likely claims for damage. It is known formally as Skanska USA Civil Southeast Inc. and Skanska USA Inc., as "Owners of the Barge M8030 Praying for Exoneration From or For Limitation of Liability."

Federal scientists have described Hurricane Sally's path and intensity as erratic. Skanska, the company claimed, took all reasonable steps to prepare for the storm, which suddenly changed direction and hit with unexpected intensity.

Barge damage to section of Pensacola Bay Bridge. Photo: Courtesy of FDOT

Barge damage to section of Pensacola Bay Bridge. Photo: Courtesy of FDOT

In the spring, judges granted Skanska’s motion to limit the contractor’s liability—based on federal maritime law—to the value of the barges, which range from $125,000 to $550,000. One court document indicates that the ruling effectively limits Skanska’s liability total to about $7 million.

After recruiting clients with television commercials, plaintiffs' attorneys later filed hundreds of lawsuits against Skanska on behalf of motorists and business owners. Among them are Yoshiko McKnight, the owner of Flowers by Yoko in Gulf Breeze, who seeks $62,000 in income she claims she lost as a result of Skanska barges damaging the bridge. Robello Lopaka, owner of another Gulf Breeze business, Aloha Screen Printing, seeks $56,000.

Other claimants are seeking smaller amounts, based on added gas costs and auto use, from having to drive farther to reach destinations around the bay while the functional part of the new bridge was shut for repairs.

An unusual decision by one judge came in August.

Magistrate Judge Hope Thai Cannon imposed a penalty on Skanska of $92,000 for wiping clean or damaging five mobile phones used by key staff members on the project—an act that effectively destroyed trial evidence, she said. According to the judge, Skanska blamed gaps in its procedures for protecting lawsuit-related phone data.

“This is a textbook case of spoliation,” meaning, the destruction of evidence, Cannon wrote in August in granting claimants' motion for a penalty.

During pre-trial depositions earlier this year, lawyers for local residents and business owner claimants tried to pick apart the detailed procedures observed by Skanska’s staff in the days and hours before the hurricane struck. Claimants allege that Skanska had ample meteorological information about the hurricane’s path to relocate the construction barges away from the jobsite. The contractor's emergency plans, according to the claimants, say that task would have needed to start 30 hours before a storm hit.

Instead, Skanska decided to keep working on the new bridge until the latest possible day and tied down the barges at the construction site so that work could continue, instead of moving them farther away, claimants allege.

The path of Hurricane Sally took a turn to the northeast. Image: Courtesy of NOAA

The path of Hurricane Sally took a turn to the northeast. Image: Courtesy of NOAA

Pre-trial maneuverings didn’t end until days before the trial started.

Skanska filed a motion to exclude all testimony and evidence about other hurricanes and storms prior to and following Hurricane Sally. The court record isn’t clear about how, or if, that was decided by the judges.

Another motion by Skanska sought to exclude deposition testimony of project manager Robert Rodgers, the third-highest employee on the project, because he was not, in the conractor's view, a “managing agent” of the project.

The subject had come up earlier in the year when Skanska Project Executive Thomas DeMarco was deposed on June 18. The deposition was supposed to be about who had specific roles and responsibilities on the bridge replacement project. He was questioned by claimant attorney Thomas Gonzalez about that and about the hurricane plan itself.

DeMarco testified in the deposition that the hurricane preparedness plan was part of the Skanska Environmental Health & Safety responsibilities, and that it includes inclement weather. Gonzalez had DeMarco show him exactly who on Skanska’s staff had responsibility for the EHS plan. The group included the project superintendent and a safety manager, field engineer and project engineer. All had signed off on the safety plan created as work on the project moved in 2016 to 2017 from a precast yard located on land to working over water.

The Pensacola Bay Bridge connects Pensacola with Gulf Breeze. Map: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Pensacola Bay Bridge connects Pensacola with Gulf Breeze. Map: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Under questioning, DeMarco testified that he and Rodgers had responsibility for keeping an eye out for weather and long-range weather forecasts and that meteorological data was supplied by a consultant, Alan Archer & Associates.

During the interrogation, attorney Gonzalez sometimes veered outside the agreed subject of the deposition—delineating responsibilities and roles on the project.

“In the process of implementing a hurricane preparedness plan, was there someone who had the role of monitoring the expenditures or budget associated with implementation?” he asked.

Skanska’s lawyer objected and the question wasn’t answered at that time.

Both sides in the case are now preparing post-trial motions and it is unlikely that there will be a ruling from the court before December.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment