Growing up on a Navajo reservation in Arizona, Jay Yazzie, now a senior environmental engineer at Brown and Caldwell, did not have running water in his home. To get its water supply, the family would take a 55-gallon drum to a livestock well or to a distribution point to obtain potable water for everyday use. He was 10 when his family was finally hooked up to a reliable supply.

Today, some 30 years later, things have not improved much, if at all, on most reservations, he says. “In some places it got better, but in others it’s gotten worse,” says Yazzie, who works occasionally on tribal projects. For every home that had a water distribution system installed, another may find its well dried up or contaminated by toxic chemicals. Within the Navajo Nation, only one in three homes has running water, while in the Hopi Nation, the tribe estimates 75% have water tainted with arsenic.

Click here to read other Engineering Justice series articles

Bringing Equity to Infrastructure Inequality

Room to Breathe: Industry and Stakeholders Seek to Co-Exist

While there is a glaring need for safe, clean drinking water for Native Americans, the inequities of U.S. water systems are seen in every area of the country. More than 2 million Americans live without running water, indoor plumbing or sewerage, according to a 2019 report from the U.S. Water Alliance, a nonprofit that focuses on getting the U.S. to understand the value of water, and DigDeep, a nonprofit that focuses on access to water as a human right.

“We treat water like an amenity, instead of a vital necessity,” said EPA’s National Environmental Justice Advisory Council in a 2019 report. “Providing water and sewage only to those who can afford to live in an area with an expensive functioning infrastructure sends the message to neglected communities that their access to clean water and sanitation is a luxury. Those who suffer greatest … are the most vulnerable, including those who are low-income and communities of color.”

“I think we’re hitting a point across the country … where everyone is thinking about how we can do our part to support racial justice.”

— Renée Willette, Vice president, U.S. Water Alliance< span>

Water inequality was there from “the beginning,” says Cindy Paulson, chief technical officer at Brown and Caldwell. Economically disadvantaged and minority communities are often located in “the least desirable areas—whether low-lying areas that get flooded, or areas that have less access to water, or areas where we decide to put our wastewater treatment plants—that theme has been in place for a long time.” While it’s good that the problem is finally being addressed, she said, “it’s a long way to go to turn the tide in the right direction.” A U.S. Water Alliance analysis says Black and Latino households are nearly twice as likely to lack plumbing than white ones. Race is the strongest predictor of sanitation access, and poverty is the key obstacle to water access, it adds.

LINGERING CONCERNS Cleophus Mooney of Flint, Mich., still must pick up bottled water to ensure his family has clean water to drink, six years after the city’s water contamination scandal was revealed.

Photo by Seth Herald/AFP via Getty Images

In Lowndes County, Ala., where 25% of the population lives below the poverty line, one out of every five homes has no sewage treatment, and homeowners can be jailed for failing to install systems that often cost more than their annual income. In Milwaukee, neighborhoods most impacted by floods are those with low-income, Latino and Spanish-speaking residents. In Baltimore and Philadelphia, water bills can be added to property taxes, leading to home foreclosures that most often affect the poor and people of color.

And in Jackson, Miss., the state’s largest city, residents—of whom 80% are Black and more than 25% live in poverty—went without water for five weeks this winter as chronic water system underinvestment led to failure during a multiweek freeze. “We have to understand that Jackson, unfortunately, is not an exception to the rule,” in terms of water system infrastructure, Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba told ENR. “We are the rule in many regards.”

With the Biden administration earmarking $111 billion for water infrastructure investment in the American Jobs Plan—including money to replace lead pipes and address water contaminants—and its focus on environmental justice, the drive to fix the sector’s systemic inequities is gaining momentum.

ALTERNATIVES More than one-third of those in the Navajo Nation (left) don’t have running water and rely on water trucks or other alternatives.

Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images

“I think we’re hitting a point across the country, the moment that we are in, where everyone is thinking about how we can do our part to support racial justice, coupled with this incredible need to invest in our water systems,” says Renée Willette, U.S. Water Alliance vice president. But the question remains, she adds: “How do we marry these two opportunities to create better opportunities for all of our communities?”

Architects, engineers, contractors and others are playing a key role in helping to right the water wrongs. “Traditionally, engineering firms do not necessarily play in the water equity or social justice space,” says Victoria Johnson, leader of the social value and equity practice at Jacobs. “So this has really been driven by our clients … really working with our water sector leaders who have been very passionate about equity and social justice over the last five to 10 years.” She points to water utilities in Atlanta, Seattle, and San Francisco that have placed water equity ahead of all other priorities. Equality in the water sector has “become the center of the conversation instead of the peripheral,” says Dana Eness, executive director of the Urban Conservancy in New Orleans, which works to lessen flooding in the city.

Growing Needs

The Flint water crisis, which began in 2014 when the city switched to a corrosive, improperly treated water supply that resulted in high amounts of lead in the drinking water, highlighted for the public what the water sector had known for years: Many cities can’t maintain their existing water systems because ratepayers can’t afford basic service, and state and federal help is scarce.

“We have many poor red and blue cities and towns across the country that can’t afford to upgrade their infrastructure and meet existing federal law,” says Marc Edwards, a civil and environmental engineering professor at Virginia Tech who, along with his students, helped bring the lead situation in Flint to the public eye. “We are putting these communities in impossible situations.” Edwards won ENR’s 2017 Award of Excellence for that effort.

"I think in the future, you'll see that the way water and wastewater is done will be in just a completely different way."

—Cindy Paulson, CTO, Brown and Caldwell

In 1977, the federal government was responsible for 63% of capital spending for water and wastewater systems. Today, that amount is 9%, according to the Water Alliance. As a result, cities like Detroit and Flint, which have seen their populations shrink while the footprint of their water system stays the same, are at a disadvantage because they can’t keep up with routine maintenance, let alone pay for upgrades.

Photo courtesy The Astra Group

“I think the industry as a whole has a real dilemma,” says Ann Bui, a Black & Veatch managing director and leader of its management consulting group’s water market business. Bui was lead author of a recent company report detailing how funding and affordability is a major obstacle for the water services in the nation’s largest 50 cities. For years utilities have been driven by a desire to keep rates low, she says, and when they finally raise them, some are unable to pay. The Sewerage and Water Board of New Orleans raised rates 10% annually for eight consecutive years, with some now unable to pay water bills based on their available income. “The water bill is not even considered” as one that will be paid, says Ghassan Korban, board executive director.

Black & Veatch has been working with New Orleans to help it better understand the affordability issue and seek alternative ways, possibly through a local assistance fund, to help customers pay their bills. EPA’s National Environmental Justice Advisory Council found in a study that 71% of utilities offer no type of customer assistance. The U.S. Senate included a water assistance fund in recent water legislation. “Unaffordable water bills perpetuate poverty,” the council said in its report. New Orleans, like most other cities, placed a moratorium on water shutoffs because of nonpayment during the pandemic, but that put the city further behind in its upgrades. The Sewerage and Water Board lost about 10% in revenue last year, Korban estimates.

Jackson found out firsthand how problematic it is to lack the funds to upgrade and maintain its existing water system when very cold temperatures froze raw water screens and crashed mechanical and electrical equipment, Lumumba said.

The city knew it needed to make updates, but it simply did not have the money. “So now we are looking under all of the rocks and shaking all of the bushes,” searching for additional cash to improve the system, he said. A major infrastructure package, like the one proposed by the Biden administration, is desperately needed to help cities like Jackson, Lumumba said.

Historic redlining and racism also led to water inequity for people of color and the economically disadvantaged, who often live in the lowest-lying areas of communities that are prone to flooding, or have treatment plants located within their neighborhoods.

In a series of recent water equity workshops, the Water Alliance determined that while storms may affect a city equally, “the capacity to respond to and recover from flooding is much lower in socially vulnerable populations that even in the best of times are struggling to function.”

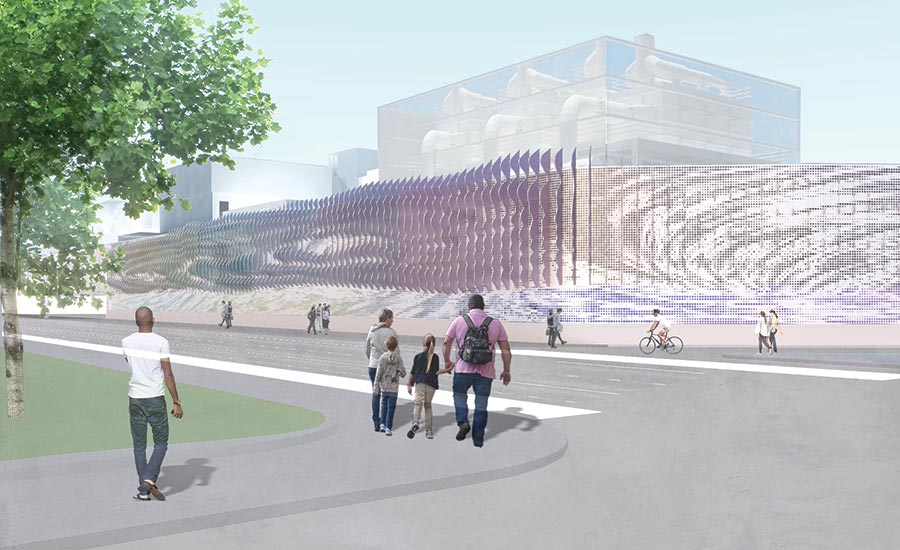

REIMAGINED Based on community input, the revamped Southeast Treatment Plant in San Francisco will feature odor control, community art and be located further way from the neighborhood when complete.

Photos courtesy The Astra Group

Vine City, a historically Black community in Atlanta, had been affected by repeated floods until a major deluge in 2002 prompted the federal government to buy out flooded homeowners. This month, a new multimillion-dollar park, built to capture up to 37 million gallons of stormwater per year, will open as a community amenity with walking paths, sports courts and a splashpad that neighbors in the economically disadvantaged area are eager to see.

HDR, which led the project’s design process, worked with the community to ensure that residents could decide what would be in their neighborhood. In the past, when the community would be invited to review a proposal for water infrastructure, residents “would show up and we’d already have the whole design complete,” says Todd Hill, deputy commissioner overseeing the city’s Office of Watershed Protection. “That has changed.”

The result is not only a benefit to the community, but the Rodney Cook Sr. Park, with bridges and sidewalks and athletic fields, will cost about $40 million, compared with a tunnel solution that would have cost $70 million, says Hill.

Similarly, the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission worked closely with the community on a $2.2-billion reconstruction of the Southeast Treatment Plant, the city’s largest wastewater facility that has been located for almost 70 years in a low-income area.

Brown and Caldwell is leading a team, including Jacobs and Black & Veatch, to build a new biosolids digester facility. Odor control, a more attractive resident-facing exterior and community programs are among improvements being made to the facility to reduce its impact on the neighborhood.

“Delivering these projects is only achievable with community acceptance, so being a good neighbor is an essential element of how we work,” says Will Reisman, press secretary for the commission.

Both the Atlanta and San Francisco developments also stress workforce development within communities of color as a way to overcome racism within the water sector. “In 2016, nearly 85% of water workers were male and two-thirds were white, which really points to a need for a younger, more diverse talent within the water sector,” says Johnson.

These initial projects seeking to make water more accessible, affordable and equitable are just the beginning of what’s yet to be done. “I think environmental justice will be addressed to a much greater degree in planning for the next 20, 30 and 50 years ahead,” Paulson points out. “The Southeast plant is still located in the low-income area of San Francisco. I think in the future, you’ll see that the way water and wastewater is done will be just completely different.”

Most see massive federal funding, as called for in President Biden’s proposals, as the main path to water equality. “It’s as vital as you can imagine,” says Korban, of the New Orleans Water and Sewerage board, about the president’s plans.

Return to series overview article:

Engineering Justice: Bringing Equity to Infrastructure Inequality

Although needs have always exceeded funding, “everyone should have equal access to water,” he says. “I mean, it’s the most basic service we provide, and we must find a way to have that happen.”