CHENNAI, INDIA—The last train that carried water into the parched city of Chennai rolled out of town Oct. 9, almost four months after officials declared the city at “day zero”—with no water for a population of more than eight million people. For those months, people lined up to get their allotment of water brought from the countryside by rail car or by tanker truck. Fights broke out, and worldwide attention was focused on this, the first major city in the world to go completely dry.

Learn how Cape Town, South Africa avoided its 'day zero'.

Even in October, though summer rains had filled the city’s four reservoirs enough to halt the trains, there were still signs all over the city of the water shortages—from multiple water tankers still on the roads to warnings at hotels to take short showers. With continued rains, Chennai Metrowater officially declared the city out of its water shortage Nov. 4.

But the danger of future dry spells for this city, and hundreds of others, persists, because of poor infrastructure, population growth and development trends—all exacerbated by increasing variable precipitation and rising heat.

“Chennai’s water crisis is not over,” says Nityanand Jayaraman, an activist in Chennai. In fact, the water crisis residents fear as much as drought is flooding. This overbuilt coastal city, once called Madras under British rule, faced a massive flood in 2015.

“When you’re flooding and dying of thirst, it’s pretty much a worst case,” says architect David Waggonner, whose firm has been involved in water solutions from New Orleans to Norfolk to China.

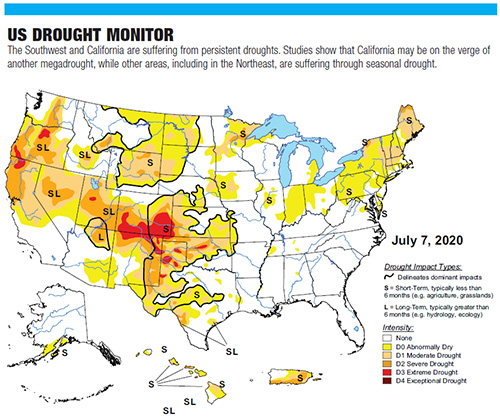

The Chennai crisis is just the tip of the spear. By some forecasts, the worldwide water crisis is just beginning. Water scarcity is one of the largest global risks over the next decade, according to the World Economic Forum. A recent study shows California on the cusp of one of the worst droughts in more than 1,000 years. Another study shows if climate change continues at current rates, water supply deficits will increase fivefold, with 1-in-100 year droughts occurring every two to five years. On the flip side, in the U.S., heavy precipitation events are expected to triple.

“I’m not really sure if we’re living in a period of floods punctuated by droughts or droughts punctuated by floods,” says Susan Butler, Jacobs’ global technology leader for integrated water resource management.

Crises have already hit Cape Town, South Africa, which neared its day zero in 2018. Since then, heavy water restrictions and shaming of overusers has reduced per capita consumption there. The city is also turning to desalination plants, groundwater augmentation and water recycling. In Perth, Australia, persistent drought has become the norm, and the city has turned to desalination and groundwater rather than surface water to supply its needs.

Chennai is responding to its crisis by building new desalination plants, improving its wastewater treatment and clearing some of the hundreds of ponds that can hold water, but which now are filled with waste and ringed with slums.

In the U.S., the most drought-prone cities, including Los Angeles and Phoenix, have taken steps to avoid their day zero by building desalination plants, supplementing groundwater aquifers and, in El Paso, Texas, building one of the world’s largest toilet-to-tap water reuse facilities.

“The number one thing is having a diverse water portfolio from multiple sources, because different sources can be impacted by varying future conditions,” says Jill Hudkins, a vice president and water leader at Tetra Tech.

Chennai’s Water Problems

In Chennai, water problems are intensified by the city’s rapid urbanization, which has nearly doubled since 1991, when the city opened its doors to technology companies. Plans call to more than quintuple the size of the city. But that growth “is limited by lack of water,” says Waggonner, principal at Waggoner and Ball, which worked with Arcadis and Deltares to develop a plan for Chennai as part of a Dutch initiative called Water as Leverage, which aimed to identify the most feasible and replicable urban water proposals in Chennai; Khulna, Bangladesh; and Semarang, Indonesia. But, he adds, “How do you stop just building and get a handle on this problem?”

The city once had 60% wetlands and 6,000 lakes and reservoirs that retained the 55 in. of rain the city receives each year, mostly in monsoon season. Today, wetlands comprise only 27% of the city, and 2,000 lakes in the state have disappeared, says Rangarajan Ramaswamy, Regional Director of Grundfos Safe Water, Asia Pacific Region. Grundfos is working in Chennai to help tackle the problems there, as well as throughout India, supplying 39,000 solar-powered water pumps that supply water to 8.5 million people.

“We should be the water capital of the country,” says Krishna Mohan, chief resilience officer for Chennai. The historic wetlands and water bodies once retained the water for later use. Now, when monsoon season hits, the rains lacks a place to rest and rolls over the landscape to the Bay of Bengal.

“The system we designed in the mid-20th century is based on early 20th century hydrology—all of a sudden there’s a mismatch. You can’t necessarily average super wet years and super dry years and say you’re ok.”

– Brad Coffey, Water Resource Manager of The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California

The region once had an elegant system with thousands of interconnected gravity-fed reservoirs, called erys. When the monsoons came, this chain of erys captured the rainfall. If one overflowed, the water would flow to the next pond.

But that system, portions of which date back 1,500 years, began to decline after the British took over India and developed land that was once used for water management. Rather than a system of decentralized erys, Chennai became reliant on a centralized water distribution system fed by four reservoirs. When day zero was declared last year, the reservoirs were at about 1% capacity.

Only about half of the households in the city have water that comes directly to their home, and many of those augment their supply with water truck deliveries. Other residents must go to a central source, usually a pump or a tank, to gather their water.

It’s estimated that up to a third of the city’s population lives on the banks of the city’s ponds and canals in informal settlements. Human and other waste is dumped into the water, and in the dry season some canals essentially hold only sewage. According to one study, as much as 264 million gallons of sewage a day is untreated and released to the city’s water bodies.

Before addressing the water problem, “you have to unlock the sewage problem first,” says Andy Sternad, who led the Chennai design for Waggonner and Ball. The project is still without funding.

The city is restoring and desilting some of the water bodies to hold more rainfall. With the help of city businesses, about 260 waters bodies have been cleaned up.

But it’s an arduous task. For example, Grundfos partnered with Hand in Hand India to restore a 2.5-acre pond in Chennai. The effort had to be done twice, because after the first cleanup, the pond was overwhelmed with encroachments and waste. Grundfos worked to educate the local residents before embarking on the second cleanup. The way the residents treated the pond after it was cleaned the first time speaks to the lack of respect Chennai residents have for these water bodies and water in general, Mohan says. In Chennai, water isn’t metered and residents pay a flat fee equivalent to $1 for their water supply.

Chennai has been working on other short-term and long-term solutions. The city has three desalination plants that generate about 48 million gallons of water per day. Tecton Engineering, together with Cobra Spain, is developing a 40-million-gallon-per-day desalination plant that is scheduled to come online late next year, and a 100-mgd plant is in planning stages.

“Over the last two years, there’s been a sense of urgency,” says Mohan. “If you want to solve the water problems, the time is now.”

IMAGE COURTESY U.S. DROUGHT MONITOR

U.S. Problems and Solutions

The U.S. may not have the same systemic political and historical problems as India, but the two countries do have climate change in common.

“When you get 10 inches of rain in 2½ hours instead of six hours, it challenges all of our systems,” says Luis Casado, director of the Gannett Fleming’s water business line.

Variable precipitation that doesn’t match historic norms is causing headaches from coast to coast, and even in the heartland, says Tracy Streeter of Burns & McDonnell, and former director of the Kansas state water office.

The state would often have flooding in the east and drought in the west. “When you get into those extremes, you have to store water to get through the longer-term drought,” Streeter says.

Storage solutions for Kansas included dredging a Corps-owned reservoir to increase capacity. The state is also developing an integrated, diverse plan to secure water from multiple sources, a strategy being used in other regions.

“The system we designed in the mid-20th century is based on early 20th century hydrology—all of the sudden there’s a mismatch. You can’t necessarily average super wet years and super dry years and say you’re OK,” says Brad Coffey, water resource manager of the Metropolitan Water District (MWD) of Southern California. The district supplies water for 19 million people in Southern California.

In 1990, more than 60% of MWD’s water came from imported sources, including the Colorado River and the California state water project. The district has set a goal to flip the ratio and get 60% of its water locally by 2040, Coffey says.

The district has dramatically improved its storage capacity since the 1990s, and today has 13 times more water storage capacity than it did in 1980, including Diamond Valley Lake, which was completed in 2000. The facility can hold 810,000 acre-ft of water—about half of a year’s supply for the district.

Above-ground reservoirs—especially traditional dams—historically a favored solution for water supply, are now often considered environmentally contentious and difficult to permit. Reservoirs adjacent to rivers and water bodies, which are less controversial, can help store surplus water when there are high river conditions, says Casado. New technologies and liners can also be used to help build reservoirs where they historically might not have been able to be built. For example, Gannett Fleming reengineered a Tampa Bay Water reservoir that had cracked, with a stair-step soil-cement system.

Water reuse, at all levels, has become one of the most cost effective and efficient ways to ensure water supply for water stressed areas.

MWD is piloting a program to treat wastewater and inject it into groundwater aquifers for future use. Such aquifer recharge programs have also been implemented in Orange County, Calif.; Hampton Roads, Va.; and Wichita, Kan. Based on the success of its pilot, MWD is planning a $3.4-billion plant that could produce up to 150 mgd of water a day—water that would normally be released into the ocean.

‘Holy Grail’ Solution

California is beginning to examine regulations that would allow for treated wastewater to be discharged just upstream from a drinking water treatment plant, a variation of direct potable reuse, Coffey says.

“It’s closing the loop a bit and would provide the program with more flexibility,” Coffey says.

Direct potable reuse—from toilet to tap—is the holy grail of water usage.

“When you see more water scarcity in communities where they don’t have a lot of options, wastewater becomes gold,” says Streeter.

One of those communities is El Paso, Texas, which for decades has been an early pioneer in water reuse programs. Currently, El Paso is piloting a direct potable reuse plant and has hired Carollo Engineers to design a 10-mgd direct potable reuse plant that will be the largest such plant in North America.

“The tech is there for sure” for direct potable reuse, says Sanaan Villalobos, vice president at Carollo and project manager for the plant. Design is expected to be finished by September 2021 and construction will begin in 2022, says Gilbert Trejo, chief technical officer at El Paso Water.

Because of its location in the desert, El Paso has adopted a widely diverse water portfolio. The city has treated its wastewater and injected it into its aquifer since 1985. It also has world’s largest inland desalination plant— which is being expanded to produce up to 32 mgd by treating the water from its brackish underground aquifer.

“The future [will have] a lot more reuse and potable reuse. That is water that is already here and that is already under our control. It will just be a matter of time before [more utilities] adopt direct portable reuse,” Trejo says.

Happening All the Time

While much of the southwest has dealt with megadroughts for centuries, drought is also an increasing concern in the Northeast and the Southeast. “It’s happening all of the time and it’s happening every year,” says Kirk Westphal, director of water resources for Brown and Caldwell. Areas like Connecticut, which rely largely on rainfall for water supply, “can’t afford to lose four months of rain,” he says.

Westphal and other experts say in addition to conservation and water reuse, the future of water supply lies in cooperation and regional sharing agreements.

“Every state is approaching stream flow protection in a silo. If they could coordinate, it would recast the world of water,” Westphal says.

Despite his confidence, the fact remains that water worldwide could be threatened by something new or unexpected.

“If we’ve learned anything over the past five years—pandemic, social unrest, climate change—water supply systems need to be buffered against things we can’t even imagine yet,” Westphal says.

With each disaster, though, comes a new opportunity to fix a growing mismatch between water supply and demand. Those in Chennai say that the drought in 2019 was no different than the drought in 2017. “We’ve been dealing with this for 30 years,” since the city began to be hit with climate change on top of rapid development, says Mohan. But with the intense attention the city received last summer, “I’m optimistic because across the groups there is a certain urgency to fix this issue once and for all. The city has a lot to learn, but I believe this problem is fixable.”