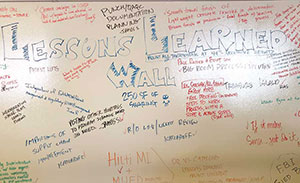

From a distance, the handwritings on the wall look like graffiti. On closer inspection, the 30-ft-long marker board in the site office of Sutter Health’s $2.1-billion hospital in San Francisco contains much more than scribbles. The 250-sq-ft mural, dubbed the “lessons learned wall,” exhibits suggestions, insights, directions, reminders, warnings, best practices—and lessons.

The public display of reflections didn’t make its debut until the 1-million-sq-ft Sutter Health California Pacific Medical Center Van Ness Campus—undergoing commissioning—was about 70% complete. The teaching tool “was an improvement to a process that was already in place,” says Rob Purcell, director of integrated design and commissioning for VNC’s construction manager-general contractor HerreroBoldt Partners (HB), an equal venture of Herrero Builders and the Boldt Co. “Throughout the project, the team had been documenting and sharing ‘small wins’ in weekly ‘big room’ meetings,” he adds.

Members of the HB team came up with the idea to transform an ordinary wall into an asset, simply by coating it with marker board paint. “If it makes sense, just do it,” says one of the 150 entries. “Start permit process earlier,” advises another. There is even soul-searching: “Did we choose the right column spacing?”

The mural qualifies as a graphic representation of the team’s collective psyche. It is one of the job’s sundry innovations, dreamed up along the five-year journey to substantial completion, reached Aug. 3.

Some others are: adding a $4-million remote prefabrication plant—not in the original budget; resequencing top-level structural steel erection, well along, to start work on the mechanical floor six months sooner; and revamping the flow of rough-in work using a time-planning system of imaginary train cars—each representing a 10,000-sq-ft work area for one trade—that “moved” around the floors and up the building.

For VNC, “we challenged every bad norm,” says Panos Lampsas, project manager for Sutter, a system of nonprofit hospitals and doctors’ groups in Northern California. “And we improved upon good norms,” adds Stephen G. Peppler, vice president of architect SmithGroup.

VNC’s leadership credits lean integrated project delivery as its innovation enabler. Lean IPD combines the Lean Construction Institute’s Lean Project Delivery (LPD) strategy to minimize waste through collaboration, predictability, innovation and accountability, with the sharing of risk and reward through a single relational contract that at minimum includes the owner, architect and contractor.

Sutter pioneered Lean IPD in California nearly 15 years ago (ENR 11/26/07 p. 80). It was a paradigm shift born of a need to cure the ills of building complicated hospitals in earthquake-prone California, where job disputes were rampant because of broken budgets and schedules. Many blamed the situation on the adversarial nature of design-bid-build delivery, combined with tortuous plan approval as a consequence of strict state rules for total hospital function during and after a quake.

Sutter’s Lean IPD abandons the time-consuming and costly tradition of preparing for litigation. The parties agree not to sue each other, with some exceptions. They operate instead as one entity, though the owner is the tiebreaker in rare cases that consensus cannot be reached. Everyone sees each other’s books. Transparency reigns.

On the 274-bed VNC, Sutter, SmithGroup and HB are signatories. The other 14 partners share risk and reward through their contracts with SmithGroup and HB.

Sutter pays all 16 firms for labor, overhead and materials—even if the project goes over budget. Sutter also audits all work, at preset hourly rates. Increased profit is determined by how much is left in the contingency fund at the job’s end.

Earlier Sutter projects had up to 11 contract signatories, but the paperwork required to audit the books was burdensome, says Sutter’s Lampsas.

“We know what is wrong. If we as an industry use some common sense, we can fix things.”

– Panos Lampsas, Project Manager, Sutter Health CPMC Van Ness Campus

VNC is Sutter’s most ambitious—and unorthodox—Lean IPD job. The credit for the unorthodoxies goes to Lampsas, considered a reformer. “We know what is wrong,” he says. “If we as an industry use some common sense, we can fix things.”

One of Lampsas’s unorthodox early moves, related to the contract, was ceremonial but intentional, designed to establish a harmonious tone. Though he helped negotiate VNC’s contract, he views it as a necessary evil—required to lay out Sutter’s business goal of opening the hospital in time for a March 2 surgery.

Contracts are obstacles to success, says Lampsas. “All the owners, contractors and lawyers set procedures so we can start fighting,” he says.

Not authorized to tear up the contract, Lampsas did the next best thing. He put the executed document in a Plexiglas box with a lock. He then had the box hung near the entrance to the VNC office, out of reach but in sight. Finally, with a camera rolling, he climbed a ladder, locked the box and threw away both keys. “It was a symbolic gesture,” he says. “We have copies.”

Kevin M. Terwilliger, project executive for mechanical contractor Southland Industries—a nonsignatory risk partner—appreciated the gesture. “I haven’t read the contract for five years,” he says.

Lampsas is proud of the locked box. But he is prouder of a more pragmatic reform, expressed by the mural entry, “Work hard to get subs paid quickly. Cash is king.” Payment lag is a sensitive subject for Lampsas, a subcontractor in an earlier life. On Sutter projects, thanks to audits, checks typically don’t get cut until 30 to 40 days after an invoice is submitted. A $500 mistake can hold up a $34-million payment, says Lampsas.

For VNC, Lampsas convinced Sutter brass, based on procedures he penned, to reverse the order: Pay first and audit invoices later. Subs got paid within five days of submitting an invoice. They also got a cash advance, based on projections for the next month’s work. That meant they did not have to get loans to advance their work.

Steve Yots, HB’s project executive and director of construction and project management, calls the reform “industry changing,” because it is a hedge against bankruptcy for small contractors.

Lampsas aims to convince Sutter to pay first and check later on all its projects. And he says the quick-pay approach can be used on any job, anywhere.

Quick payment and ignoring the contract exemplify Lampsas’ leadership style, which is based on respect for every participant in a project, no matter the rank.

“We are going to build the hospital like a family,” he told all the members of the team, again and again. “Rule #1 is have fun,” he says.

“This is the pinnacle project of my career”

– Kenneth A. Kaplan, Senior Project Manager, Rosendin Electric

“Panos is our biggest cheerleader,” says Yots. “If we got complacent, he would challenge us to make the most money we could. You never see that from an owner.”

SmithGroup’s Peppler, with nearly 50 years of experience including 25 designing hospitals, adds, “This absolutely has been the most rewarding experience I have ever had and a path we should follow.”

Kenneth A. Kaplan, senior project manager for trade partner Rosendin Electric and a 40-year construction veteran, agrees: “This is the pinnacle project of my career.”

Collocation

Under Lean IPD, design and construction partners collocate at the site office to quicken the pace of decision making, create the collective swim-or-sink mind-set, and nurture consensus-building for decision-making. “Everyone was empowered to make decisions within their expertise, not just supervisors,” says Yots. That saved time, he adds.

All the major players are trained to use LPD’s virtual tool kit. One tool is Target Value Design, in which designers and constructors design together in system-related budget-conscious teams. Another of LPD’s many tools is the Last Planner, a process designed to produce reliable workflow.

Still, after construction started in 2013, it took nine months to a year to build teamwide trust. This was largely because some players were either suffering from a mistrust disorder or they were so set in their ways that change was not easy.

But by all accounts, Lean IPD, Lampsas-style, works. At VNC, where the maximum design and construction cost was estimated at $1.3 billion, the team reached substantial completion on time, with $23 million left in a contingency fund that started out at $37 million.

Of that, Sutter gets $11.5 million. The other half is split by SG, HB and the other risk partners. “Not many IPD projects return the contingency,” says Yots.

There are other positive indicators. In terms of safety, the industry’s average incident rate is 1.6. VNC’s is less than 1, says the team. Workers compensation is typically $1.20 per labor hour. On this job, it is 13¢ per labor hour.

The project is covered by an integrated project insurance program from Zurich Insurance, paid for by Sutter. The risk-reward partners are covered, as are most of the subs. “We get better protection for everyone, and the contractors can’t charge us for their insurance,” says Lampsas.

Another yardstick was the pace of construction, which HB’s Purcell says was 24,000 sq ft of space put in place per month. In San Francisco, the average pace for hospital construction is 10,000-12,000 sq ft per month, he adds.

Troubled Past

The job started out as the Cathedral Hill Hospital, designed by Skidmore Owings & Merrill with SmithGroup and Turner Construction as the contractor. That project fell apart in the early 2000s, largely because it was over budget and the parties could not agree on contract terms.

In 2007, the VNC team, with SmithGroup and structural engineer Degenkolb Engineers remaining from the earlier job, started a redesign.

Innovation began during the validation phase, when Degenkolb suggested viscous wall dampers—instead of Cathedral Hill’s complicated and costly base-isolation system—to supplement the steel moment frame’s seismic resistance.

Wall dampers are attractive because they are simple and can be hidden behind the facade between windows, says Jay Love, a Degenkolb senior principal. But the system, used in Japan for 30 years, had not been adapted for use in the U.S.

Consequently, Degenkolb worked with the supplier Dynamic Isolation Systems, the structure’s peer reviewers and the regulatory authority—the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD)—to develop a prototype testing program and nonlinear seismic analysis.

“We tested six full-sized dampers at UC San Diego, putting each through 25 tests to determine specific design properties,” says Love.

The 119 dampers are located on eight floors. A typical damper is a shop-welded steel box, 7 ft long by 12 ft in height. A steel plate, called a vane, is inserted into the box from above. The box is then filled with a viscous polymer liquid that surrounds the vane.

At each location, the box is bolted to the girder below and the vane is bolted to the girder above. That allows the vane to move freely in the box, constrained only by the liquid, says Love. During a quake, as the vane moves through the polymer, it dissipates the seismic energy and helps control lateral displacements.

The dampers allowed Degenkolb to reduce the sizes and locations of the moment frame’s members. And there was an overall cost savings for the structural system, says Love.

OSHPD, which granted VDC a structural building permit in April 2012, approved the dampers under another significant VDC innovation—electronic, collaborative and phased plan review. That reduced approval time, compared to traditional paper review to 10 months, from 18, according to HB.

VNC was “the first large, costly project OSHPD reviewed electronically.”

– Paul Coleman, Deputy Director, Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development

VNC was “the first large, costly project OSHPD reviewed electronically,” says Paul Coleman, deputy director of OSHPD’s facilities development division. “They were pioneers … and helped us to define the right approach for the future.”

Communication was important to the VNC team. Tuesday was the day for weekly big-room meetings, with about 100 in attendance. Wednesday was risk-opportunity meeting day. There, signatories and at-risk partners decided whether to spend contingency money to add value.

The core group consisted of Sutter’s Lampsas, HB’s Yots, SmithGroup’s Peppler, Southland’s Terwilliger, Rosendin’s Kaplan and CPMC’s Jim Benney, representing the hospital’s users. They met every other week.

There was also a safety leadership team that met regularly. Work was modeled, coordinated, prefabricated and sequenced for safe production. All workers were authorized to stop work if they deemed something as unsafe.

Setting Project Culture

Every quarter, Sutter would rent an event space in a nearby hotel for a “big big room” meeting of some 300 players. The goal was to set the project culture, share a meal, get to know each other, play games and have fun.

There were also short stand-up meetings daily, to confirm commitments were on track. “We never waited a week to find out that something was going to go sideways,” says Kent Hetherwick, a SmithGroup principal.

“We never waited a week to find out that something was going to go sideways.”

– Kent Hetherwick, Principal, SmithGroup.

At the meetings, the players often conferred on logistical issues. The full-block site, hemmed in by active city streets, had little lay down and staging space. That meant just-in-time deliveries.

A discussion in 2014 about the need for off-site storage morphed into a decision to spend three months—and $4 million not in the budget—to set up an 80,000-sq-ft prefabrication plant on Treasure Island, seven miles away. There, up to 100 workers preassembled plumbing, lighting and other in-wall systems and built partial mockups.

“We spent $4 million to create value,” says Lampsas. “It was never just save, save, save.”

The island also offered a couple acres of storage space. That helped with the need for just-in-time deliveries.

It would take three years to fabricate the 1-million lb of ductwork at Southland’s plant in nearby Union City. If production stopped, even for a few days, it would throw off the schedule at the site.

Instead, as ductwork came off the line, it was protected and trucked to Treasure Island, where it was stored on 36 leased flatbeds, at the ready for just-in-time delivery to the site. “Our peak delivery day had 33 trucks delivering riser shafts, ductwork and sections of air handling units,” says Southland’s Terwilliger.

Another VNC innovation midstream, this one to schedule the workflow of rough-in activities, including framing and sheetrock, was an LPD system that uses virtual trains as part of a time flow mapping system. Each trade would move through each virtual train car, one after the other, for an agreed-upon time. Each car cordoned off a 10,000-sq-ft work area.

“We spent many hours and rigor to define and agree on the flow, batch sizes, sequence of work and conditions of satisfaction for reliable handoffs,” says HB’s Yots. The planning drew in the superintendents and leaders of the crews doing the work.

In a train car, each trade got to work by itself, Yots says. That “is not normal in our industry at all,” he adds. The system aided the tracking of production hours by trade and area, providing the opportunity to increase efficiency by tweaking sequences as needed. “If a trade wasn’t hitting production targets, we could move the train car up sooner,” says Yots.

For example, workers installing fire sprinklers were lagging. Their representative attended a risk-and-opportunity meeting and said he needed another $385,000 to speed things. “We said, ‘Whoa, let’s see what we can do differently,’ ” Yots says.

Part of the problem, the team discovered, was the sequencing of that trade’s train car. The solution was to move the sprinkler car ahead of other trades. “Sprinklers went in first, even before the fire resistance, and production greatly increased,” says Yots.

The sprayed-on fire-resistance team also came in to help brainstorm ways to improve lagging production. One adjustment was to move the mix hoppers closer to the spraying area, so sprayers could communicate with the mixers. A two-hour meeting saved $870,000 from the contingency fund, says Yots.

Another work-around happened after the adoption of two separate trains, leaving one of the finish trades without enough labor for two crews. To help out, Boldt brought in 18 carpenters from its main office in Appleton, Wis. The recruits lived in a hotel for four months.

“It cost a lot of money, but delaying the job would have been more expensive,” says Yots.

Sequencing Change

A sequencing change, when steel erection was more than two-thirds complete, involved delaying some top-floor framing to ease the installation, by crane, of the top-floor central utility plant. The disruption allowed work on the CUP to begin six months sooner.

First, the team leaders asked the steel contractor, Herrick, to slow down production so they could rethink the normal sequence. Then, they asked Herrick to demobilize and return after the CUP was done, offering the steel contractor extra compensation.

“We were one team, working for the overall benefit of the job,” Yots says. “Ninety-nine percent of the time,” jobs are not demobilized, he adds.

Still, the sequence change was not straightforward. At the time, crews had yet to cast concrete on metal deck for a couple of levels below the CUP. “The question was: ‘Can we physically load the building with CUP equipment, then have concrete poured down below?’ ” Terwilliger says. The answer was yes, with some restrictions.

The VNC team is frank about the lessons learned on the project. Next time, for example, there will be a full mock-up of a patient room and bathroom, rather than a partial mock-up of behind-the-wall elements. “We would have caught some construction problems earlier,” Terwilliger says. Similarly, the time flow mapping system will have the same rigor for finish activities as for rough-in activities.

The team has plans to document all lessons. Each will be captured on paper and digitally—enhanced by photos, anecdotes and process maps—to provide pearls of wisdom for posterity.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment