States are beginning to act on what one industry expert called this year’s “headline emerging issue” for the environmental sector—the cleanup of fluorinated chemicals in at least 40 states that could affect at least 1,500 drinking water systems. While some sites await federal standards on the category of chemicals known as PFAS or PFCs, state standards provide clarity until or unless a more stringent federal standard is established.

New Jersey became the first state to establish a maximum containment level (MCL) in drinking water for perfloronanoic acid (PFNA) of 13 parts per trillion, which went into effect Sept. 4. The state is expected to establish an MCL for perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) soon. It approved a 14 ppt limit for perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) in November 2017, but it has yet to go into effect.

“New Jersey criteria automatically becomes the groundwater cleanup standard, and will force cleanup of sites to that standard,” says Jeff Tittle, executive director of the New Jersey Sierra Club. The contamination is “pervasive,” he says, including at the state’s Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst.

The highly toxic group of chemicals once used in nonstick products have been linked to some cancers in humans and can lead to liver damage, thyroid dysfunction, metabolic and immune system problems.

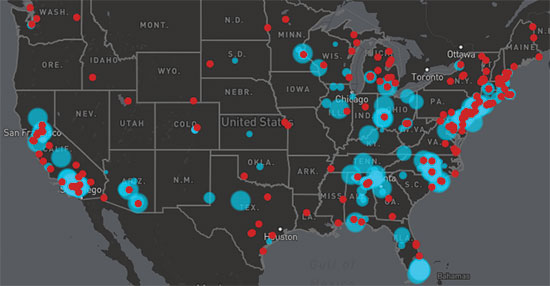

According to the Environmental Working Group’s research, as of July 2018 there were 172 known PFAS contamination sites in 40 states, more than three times the number of known sites in 2017. Map courtesy of the Environmental Working Group

The Environmental Protection Agency has identified the chemicals as a problem and held listening sessions around the country about the contamination this summer. But the agency has not yet set drinking water standards for the chemicals. EPA issued a drinking water health advisory, not a standard, in November 2016 of 70 ppt for PFOA and PFOS.

The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry in June released its health standards for 14 chemicals in the PFAS group and suggested much stricter limits. The compounds are resistant to biodegradation, persistent in soil and water, and leach into the groundwater, according to the agency.

“Clients are interested in clarity,” says TetraTech’s Leslie Shoemaker, executive vice president of operations. In addition to military installations, Shoemaker expects cleanups will be needed at commercial and manufacturing sites. But before cleanups can occur, standards are needed, she says, noting that cleaning up without specific criteria could lead to requirements for further action later.

The military is likely to spend millions on cleanups at installations and on contamination that has migrated to communities. The Air Force, which used aqueous film forming foam (AFFF) containing the contaminants to fight fires, only has to follow EPA’s advisory, says Mark Kinkade, a spokesman at the Air Force Civil Engineering Center in San Antonio. But it will look at properly established state standards, he says.

The Air Force has identified 203 installations with fire training areas or crash sites where AFFF was used. Some 190 sites are expected to require further investigation. The Air Force has spent $241 million on actions to reduce the chemicals, including using filters at 19 installations to clean contaminated drinking water. The Department of Defense has investigated 2,668 groundwater wells and found 61% of them had contamination levels higher than EPA’s health advisory.

The Air Force primarily uses granular activated carbon filters to clean drinking water, but there is a search for better technologies. The Air Force is partnering with academic researchers to find a technology that will reduce the chemicals’ impact.

Congress has begun to tackle the issues, with bills that would require cleanup and provide some funding to clean up the chemicals, but nothing has yet become law.

Other states too are addressing the problem. Newburgh, New York has spent $22 million on a new filtration system to eliminate the chemicals from the city’s water system, and Vermont and Minnesota have adopted standards stronger than the EPA’s guideline, while Michigan has adopted the EPA’s guideline.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment