This month, Åsa Bergman completes her tour of European markets new to Sweco, the Swedish design firm giant she now leads. As president and CEO of one of Europe’s largest designers—officially in the job since April—she is on a mission to spread the decentralized management structure that appears to have served the company well at home.

Bergman should know. During her six-year previous role running the architect-engineer’s largest unit, Sweco Sweden, the 27-year company veteran saw both its revenue and employee count nearly double.

The game-changing 2015 acquisition of Netherlands-based Grontmij N.V. has fueled the Stockholm-based parent firm’s push farther across Europe.

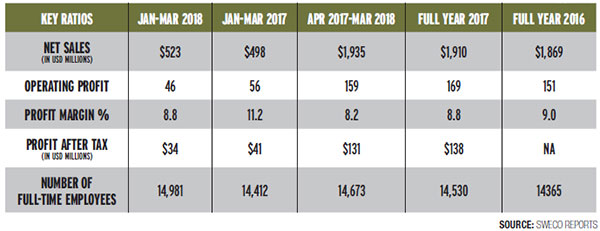

Before the deal, Sweco was an 8,500-person firm that focused largely domestically, with a small number of subsidiaries in nearby nations and an array of export projects around the globe. Now the publicly traded firm has 14,500 staffers in 14 countries and sales of nearly $2 billion. It ranks at No. 19 on ENR’s list of The Top 150 Global Design Firms, up from No. 21 last year (see story, p. 34).

Even with the firm’s solid metrics, her own executive management track record and recognition in Swedish business circles, Bergman is a relative unknown to many peers in the global design world and to investors, and she has a tough act to follow, observers say.

She succeeds Tomas Carlsson, credited with leading Sweco’s upward momentum during his five-year tenure. He left the firm in January for a role he began in May as CEO of Swedish contractor NCC AB, a former employer whose weak margins he was brought on to fix. NCC’s operating profit fell 15% last year.

Carlsson “improved [Sweco] rankings on employee [and] brand attractiveness, which supported growth rates,” says Viktor Lindeberg, an analyst with Carnegie Investment Bank AB, Stockholm. He credits the former CEO with the “successful acquisition and consolidation” of the 6,000-person Grontmij. Bergman “has been exposed to the Swedish market but needs to get up to speed on the dynamics of how other markets are developing,” says Lindeberg.

Related Article:

Sweco Digitizes The $1.4-Billion Megaproject Next Door

Management Veteran

Bergman emphasizes that she is a familiar face in the Sweco boardroom—part of the group executive team that shaped major decisions, including the Grontmij deal. She says her plan to recruit up to 3,000 new hires across company units is supported by high marks in workplace culture and employee commitment from recent employee satisfaction surveys, “an important tool for us … as the basis for our development going forward,” she says.

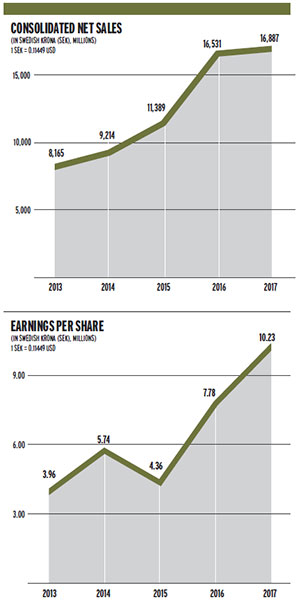

A degreed civil engineer, Bergman worked her way through the company in different regions and was key to doubling home-market sales. As a co-architect of the path taken so far, “I have a strong belief that this is the right strategy,” she says (see charts below).

Since Sweco’s appearance on the Nasdaq Stockholm exchange in 1998, “very little has changed in how … we operate,” says Chief Financial Officer Jonas Dahlberg. “And we have no plan to change.” Growth, at about 15% annually, has been two-thirds fueled by acquisitions, he adds. The firm has “made more than 100 acquisitions in the past decade and so far so good,” says Lindeberg. “We have not seen any acquisitions that have affected the company adversely.”

Sweco acquired in 2013 the Swedish government-owned transportation design firm Vectura, with 1,200 staff, but pushed the envelope with the Grontmij deal two years later. “We had the vision of becoming Europe’s market leader for a very long time,” says Bergman, 51.

Sweco acquired in 2013 the Swedish government-owned transportation design firm Vectura, with 1,200 staff, but pushed the envelope with the Grontmij deal two years later. “We had the vision of becoming Europe’s market leader for a very long time,” says Bergman, 51.

After a search for a compatible purchase, she adds, “we found each other.” Sweco’s $387.4-million cash-and-stock offer was about a 22% premium over the firm’s stock close on that day. The Grontmij purchase provided Sweco with units in Holland, Denmark, Belgium, the U.K., Germany and Sweden, along with smaller operations in Poland, Turkey and China.

At the time of the deal, Grontmij was three years into its “back on track” plan to rebuild its weakened financial position. Integrating Grontmij into Sweco was a task given to Ann-Louise Lökholm Klasson, now Bergman’s successor as president of Sweco Sweden.

With a background in international business and project management, she was former CEO Carlsson’s choice for the job, she says. “In Sweco, there was huge [pride] that we had made this acquisition. For a Swedish company to … be international was very big here,” says Lökholm Klasson. “On the Grontmij side, their numbers were a bit low and they could look at Sweco and see that we [knew] how to do this business. They were very willing to learn and listen,” she adds.

But with the new geographical spread and diverse skill sets, knitting Grontmij into its new parent was “very complex,” says Lökholm Klasson. The master spreadsheet of required tasks had “thousands of activities,” she says.

In the three years since the deal, Sweco changed Grontmij’s management, and “we have developed in a good way month by month,” says Bergman. “Now we have growth back to where we want.”

Last year, Sweden was Sweco’s most profitable market, recording a 12% operating profit. The largely Grontmij-based West Europe business achieved a 7% margin and Central Europe 6.4%.

To raise Grontmij’s 4% margin, where it was at the time the deal closed, “we established a plan in three horizons to create value,” says Dahlberg. The first included cutting head office, IT and other costs in former Grontmij units, and restructuring the unprofitable Danish and Norwegian businesses. The second leg is “about customer focus and internal efficiency,” he says. The third aims to exploit the group’s new footprint. The markets in which Grontmij operates are fragmented, with no single design firm controlling more than 5%, says Dahlberg.

So far, Sweco’s strategy appears to be paying off. In its sector, it is the Nordic “top performer of the listed companies,” says bank analyst Lindeberg.

Sweco is “one of our strongest competitors [and] doing really outstanding work,” says Lars-Peter Søbye, president and CEO of Denmark-based design firm COWI A/S. “But we are different in our approach. We go mainly for larger contracts in core sectors. That is our strategy, and it has worked well for us,” he adds.

Close to Customers

Bergman traces to Sweco co-founder Gunnar Nordström, who died last year at 88, the firm’s core decentralization strategy, with small teams and slimmed-down management structures working closely with clients. In 1958, he helped create Swedish architecture firm FFNS, which acquired the designer VVB Group in 1997 to form Sweco. The Nordström family is the firm’s biggest shareholder in terms of voting rights and second largest by share value, says Dahlberg. Nordström’s son Johan chairs the firm.

Sweco contracts include several for the $1.4-billion Slussen flood control and infrastructure upgrade in Stockholm (See related story).

But its continuing strategy to stay close to customers is most evident in its many smaller projects. Of some 70,000 current jobs, Bergman values the average fee at under $50,000, with a median worth below $10,000.

Small projects are no less profitable than the major ones, adds Dahlberg. Customers “need to have expert service and design on those small projects, so they are really important to us,” says Bergman. “That is part of our strategy to go for the small and midsize projects and that is also why [we have] the decentralized organization,” she adds.

Geographically, Sweco is focusing on European countries with similar market conditions and cultures. In eight “home markets”—Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the U.K.—it aims to be among the top three in size and “when it comes to the customer, preferred … in a region, in a country or in a specific niche,” says Bergman. “We should also be the preferred choice of the employees.”

Sweco also has smaller companies in Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Lithuania, Poland and Turkey.

In almost all of Sweco’s new markets, “we have the potential of becoming the market leader … before we start to look somewhere else,” adds Bergman. Meanwhile, “we are not jumping into new countries.” The company sold its three small firms in Russia in 2012 as economic and work conditions there deteriorated, four years after buying them at a time of higher oil prices, says Bo Carlsson, Sweco president for Western Europe.

Among new Sweco companies being reshaped is its U.K. unit, now run by Max Joy, a retired British Army colonel with 28 years in the Corps of Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers. He “had no fixed ideas of how things had to be,” says Carlsson, who hired him in 2016.

“What we are trying to do is differentiate ourselves from the competition, and the Nordic culture is very important,” says Joy, noting that the U.K. team has grown by about 150 members to 880 since the Grontmij acquisition, and there are plans to reach 1,100 by 2020. With Danish origins, the U.K. company “was used to the Nordic way of thinking,” says Carlsson. But it also had a “very British structure,” with more management tiers than the Sweco model.

Source: Sweco Reports

Looking Ahead

The U.K.’s planned departure from the European Union that is set to occur on March 29, 2019, could hinder growth plans.

Nobody knows what the impact of Brexit will be, but “we don’t expect it to be positive,” says Dahlberg. He is not unduly worried, however, since at present, the U.K. market “is less than 5% of our total exposure,” he adds.

Joy worries, however, about his post-Brexit ability to continue recruiting staff from EU countries once free movement ceases, as seems probable. But as a relatively small U.K. market player, “there will always be opportunities to grow,” he says.

Outside Europe, Sweco has projects around the world, with offices in some 25 countries. With a staff of about 70, the firm’s Indian resource base in Delhi services work in Europe and elsewhere. In China, Sweco architects are designing a new 300,000-sq-meter district in Shanghai at a former industrial park site.

Company engineers are working to rehabilitate the small rock-earthfill Kafue Gorge hydro plant in Zambia, which a Sweco predecessor firm designed nearly 50 years ago, and also are returning to another project of an earlier era in a contract to reinvigorate landmark water storage structures in Kuwait City that were designed in the 1990s.

Kaj Möller, Sweco head of export, sees the firm’s global business as a way to gauge the strengths of foreign rivals. “If you do it right, it can be very profitable,” he says.

Workplace diversity also has been a long-term strength at Sweco. “This is about being an attractive employer,” says Lökholm Klasson.

“To be able to design future society and come up with a solution that will fit with all of society … you need both women and men,” says Bergman. Women lead Sweco operations in Sweden, Norway and Central Europe, including Germany, and hold 30% of senior roles in various units and half of the 11 corporate board seats.

At 35%, the proportion of women in Lökholm Klasson’s 6,000-person unit matches that of the overall Swedish workforce, according to company data.

But the challenge remains in Norway, where Sweco unit President Grete Aspelund says she is “the only woman I know in a position like this” in the country. She joined Sweco in 2016 from a role as CEO of a certification and inspection firm. Sweco recruited her to correct the Norwegian unit’s “lack of leadership,” says Dahlberg. Recording 8% growth so far this year, 2018 “looks great,” says Aspelund.

Meanwhile, Bergman is gaining more attention in global circles. She was cited last year along with other women managers by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development in the group’s first-ever recognition of “women leaders who show the way toward an equal and sustainable future,” and she was a presenter at the first World Circular Economy forum in Helsinki.

The latter event in 2017 drew 1,500 scientists and experts from more than 100 countries to explore how the circular economy, which is based on sustainability principles, can achieve the ambitious U.N. Agenda 2030 and its sustainable development goals.

In gaining an honorary doctorate in May from MidSweden University, Bergman described the award as “a receipt that the issues I have driven about leadership, sustainability and gender equality have been reaffirmed not only within the company but also in our world.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment