Construction could begin as soon as next year on a 240-mile high-speed rail line between Houston and Dallas if permitting goes smoothly, according to officials. Around the same time, investors hope for a record of decision on an effort to bring magnetically levitated high-speed rail to the Northeast Corridor.

This month, the private developer Texas Central hired Bechtel to serve as project manager for the Texas Bullet Train project. Fluor Enterprises and Lane Construction Corp., with WSP, are refining and updating construction planning and sequencing, scheduling, and cost estimates based on the Federal Railroad Administration’s draft environmental impact statement (DEIS), released late last year.

“The DEIS was a major milestone because it gave a single preferred alternative,” says Holly Reed, managing director at Texas Central. “We are working on the environmental issues brought up in the report and in the public input process. Those will inform the environmental impact statement that will come out by end of this year.”

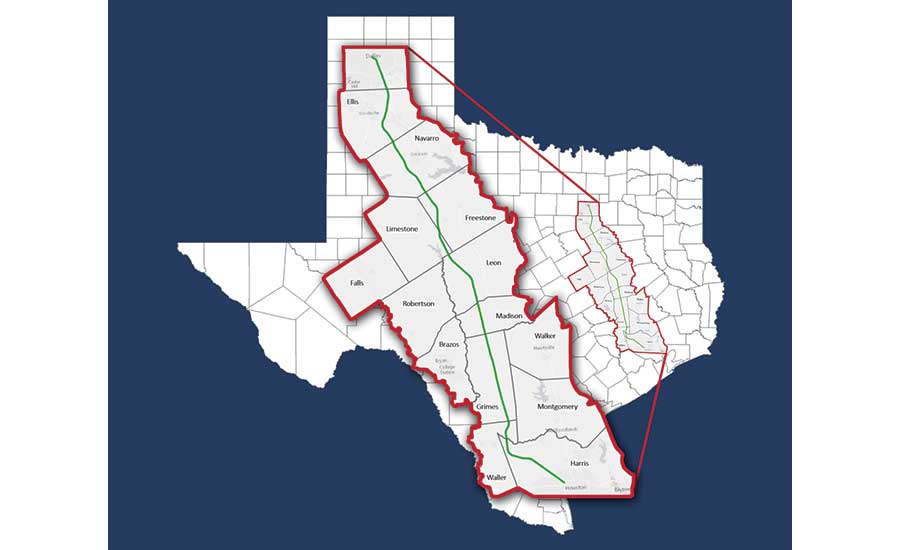

The preferred route for the project, estimated at $15 billion to $18 billion, includes three stations: in northwest Houston, south of downtown Dallas and in the Brazos Valley. “The route is straight and flat, near no bodies of water or mountains and only 500 feet of elevation change,” notes Reed. Trains would carry passengers between the two cities in 90 minutes.

The project needs to receive a final environmental permit and a rule of particular applicability, since there currently exist no trains operating at 200 mph in the U.S. “We’re focused on how to bring this [Japanese] system with a 53-year safety record to the U.S.,” Reed says.

While the Texas bullet train will utilize sixth-generation Shinkansen steel-wheel technology, the plan to connect Washington, D.C., and New York City in one hour would utilize another Japanese technology—superconducting maglev, capable of 300 mph speeds.

“At this point we have winnowed the alignment down to two alternatives, either to the east or west of the Baltimore-Washington parkway,” says David Henley, project director with The Northeast Maglev (TNEM), the private developer driving the effort. “We have our preference for the eastern side because there are less implications for residents.”

TNEM hopes to get an official preferred route choice from the FRA by end of next year for the first phase, which would speed passengers between Washington, D.C., and Baltimore in 15 minutes. About 75% of the construction would entail tunneling, notes Henley.

The 40-mile D.C.-Baltimore stretch could cost up to $12 billion. TNEM has procured $5 billion from Japan.

Noting the progress in both these privately-developed HSR projects, Henley says: “Either it’s a trend or a very happy coincidence.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment