When the astronauts operating the robot arms of the space shuttle lift the big modules into place to be fastened to the space station, motor-driven bolts will spin into captive nuts to make the structural connection. To ensure fit, only one nut in a pattern is fixed. The others have conical entries and can shift slightly along differing vectors to ensure alignment.

|

| (Drawing by Nancy Soulliard, based on image, courtesy of ZipNut) |

But even though those connections have been largely automated, there is a great deal of hand work to be done. The big, bulky space suits, which become nearly rigid when pressurized, make hand and arm movements very tiring, so work plans and tools are designed to minimize motion.

One of the standard devices is the 3/8 in.-drive, Handheld Rotary Device, a 13-lb, cordless, programmable, power wrench made by Swales Aerospace, Beltsville, Md. The HRD's onboard computer accepts 14 settings for preset speed, as well as number of rotations and torque, stopping at whichever of the last two comes first, providing a potential warning for bad connections. If the torque setting is reached before the specified rotations, for instance, it could be a sign that something is in a bind and a joint might not be properly closed and the digital display warns that something may be wrong.

|

Settings can be changed, even with an astronaut's bulky gloves, by rotating rings on the barrel. The HRD is made of aluminum, titanium and stainless steel. The 39 volt battery is good for 80 fasteners at the maximum torque of 25.0 ft-lb and can be exchanged on a spacewalk.

The astronauts also have a Swales right-angle programmable ratchet tool, which has an umbilical cord to its belt-mounted controller. The long-handled device can be used as a power tool for torque settings of up to 25.0 ft-lb, or as a manual torque wrench for settings of up to 75 ft-lb. A wide range of extensions and sockets, all drilled or ringed to accept tethers, are also provided.

|

| Rotation device ( Photo by George Knapp/ZipTechnologies) |

Swales also makes a range of high torque pliers and electrical connectors. The tool line also includes a variety of retractable tethers�little boxes that can be fastened to structures or the tool belt to keep items like�nuts and sockets from dropping overboard. The entire line can be seen at http://www.swales.com.

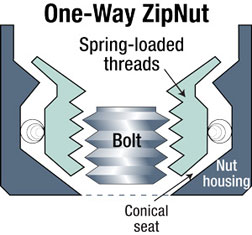

Another elegant little connector NASA uses where motorized bolts won't work is the "ZipNut," a custom-made nut whose vertically split threads fit loosely in a well within the nut, wrapped by a ring of stainless steel coiled spring. The spring presses the thread collar inward. The nut can be "run down" the bolt simply by pressing it down it. The spring loaded threads just open up and let it pass, but close back on it when it hits home so its threads nest snugly with the bolt threads. "With these things snapping into the threads, they engage the full surface of the male unit, rather than just pulling on part of it, to get a perfect match," says George Knapp, one of the two partners of ZipNut Technology LLC, Falls Church, Va.

|

| (Photo by George Knapp, Zip Technology LLC.) |

The nut is tightened by giving it a turn or so, and then another design feature goes to work: the funnel-shaped face of the base of the thread well means that when force is applied to pull the nut up the bolt shaft, the pressure of the cone against the thread jaws compresses them tighter against the bolt. The harder you pull, the tighter it gets. And because of the conical seat, they tend to grip harder when pulled against and even get tighter, rather than looser, with vibration.

The company calls the simple configuration just described a "one-way ZipNut", because although it can be put it on by pressing it down the bolt, it has to be unscrewed the old fashioned way. A more sophisticated version, which NASA used extensively during repairs of the Hubble Telescope when astronauts had to install some items, and then remove them again as part of the process, is a "two-way ZipNut." It has a knob built into the top that lets you give the hub of the nut a counter turn to spring the threads open, which lets it be lifted of as easily as it is put on.

"They all come in on a special order. The outer housing could be hex or round� all sorts of things," says Hank Hulme, managing partner. "The capacity is whatever the strength of the material is you want to make it out of. The threads do not strip."

A number of fire departments are using the two-way ZipNut in hose fittings for making quick connections and disconnections. They are also being used for some gas line applications. But in general, with the exception of some specialty applications, ZipNuts are not getting wide application�yet.

The hold-up to wider use, say Hulme and Knapp, is a legal one. They say they invested in the company 10 years ago, shortly before the inventor ran into serious legal problems in Nevada and the courts seized the assets of his company. Hulme and Knapp were able to buy the patent from the court for $100,000 a year and a half ago, but because the plaintiff has appealed the case repeatedly through the subsequent years, they say they have not been able to attract the kind of investment they would need to go into mass production.

"That's one reason the company has not been able to go gangbusters," says Hulme. "Every time venture capital comes around there is always something better to invest in than a lawsuit."

As it is now, prices start at $15 for a simple � x 20 standard thread one-way ZipNut. "A relatively simple double zip may be $100, and one with an elaborate outer body, specialized materials, could be $1,000," says Hulme.

The good news for Hulme and Knapp, however, is that the case has nearly exhausted its appeal options, and they are hopeful that they will have clear sailing for their product soon.

"We're on the precipice, ready to jump, or fly," says Hulme. Information on ZipNuts can be found at http://www.zipnut.com.

Related Links:

Related Links:

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment