|

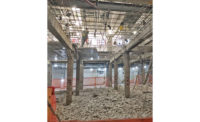

| OLD AND NEW Aging housing is torn down as units rise at San Diego naval base. (Photo by Lenska Aerial Images for Clark Realty) |

By the mid-1990s, the condition of family housing at one U.S. military base had become such an embarrassment that a base engineer suggested that he was the biggest slumlord in his city. Aging and often poorly maintained housing stock was rampant at the nation's bases and installations and was becoming a major recruiting disincentive.

|

| (Photo by Charlotte Kraenzle/Clark Realty) |

Lacking resources and management skills to quickly renovate or replace 300,000 units of family base housing, the U.S. Dept. of Defense decided to enlist the private sector as "partners." In 1996, Congress authorized DOD to obtain private-sector financing and expertise to improve housing. The Military Housing Privatization Initiative (MHIP) allowed the armed services to provide loan and rental guarantees, make direct loans, invest in companies or partnerships or convey or lease existing military property.

Under the plan, private companies would partner with the armed services to use the revenue from soldier and sailor housing allowances to leverage big loans needed to more efficiently bring base housing up to middle-class standards. But the early good intentions ran far ahead of the ability to deliver, and DOD got bogged down in a lawsuit over contract fairness in one of its first private housing deals, at Fort Carson, Colo., a large base near Colorado Springs.

The military is learning from such mistakes and is pushing to have the private sector build or expand more than 50,000 housing units in 2003, twice as many as the previous year. New competitors are breaking into the business, such as Atkins Americas, an Oklahoma City unit of the U.K.'s Atkins Group of Cos., lured by the prospect of 50 years of profit under very long-term contracts. Click here to view table.

But a number of construction services firms have been put off by a still long and costly contracting process, or have become discouraged by what they see as too much risk in lengthy partnerships. Others worry about making complex deals with military personnel, who work in an insular world of their own. "It's been a culture shock," says one firm that was selected. To bridge the gap, some contenders are employing retired officers to help them win contracts. Click here to view map.

With war in the daily headlines, projects now also involve patriotism as well as profit. The Navy's partner on a large, multi-site installation at its San Diego base speaks with pride of putting families of uniformed service people in beautiful new homes. "Given what it is and the quality of the finishes, we think it looks just like the neighbors building $700,000 condos," says Joe Schafstall, a development manager for Clark Realty Capital, a unit of the Bethesda-based construction giant. The firm is a partner with property manager Lincoln Property Co., Dallas, on the San Diego housing project.

Each deal has been different, tailored to local base needs and the approach taken by the military. The program's early years saw many partnerships on small- and medium-sized projects with design-builders who also were developers. These included Hunt Building Corp., El Paso, which is the sole or joint venture partner on six bases; and FaulknerUSA, a design-builder and developer created last year by the merger of Landmark Organization and Faulkner Construction, both based in Austin, which has won work on three bases. While developers usually lease land from a service to build on-base housing, FaulknerUSA and the Navy jointly purchased a piece of land to develop for a housing project in Portland, Texas.

|

| DEDICATED Naval officers open San Diego project. (Photo by Charlotte Kraenzle/Clark Realty) |

Other private-sector players now are maneuvering their way onto teams and battling through the expensive six-month to year-long evaluation and selection process to ink the complex deals. Last month, the Army designated a team led by housing manager and developer GMH Associates, Newtown Square, Pa., for Fort Stewart and Hunter Army Airfield bases, about 40 miles from Savannah, Ga. The team also includes Atkins Americas.

Those companies and others now have their eyes on one of the largest prizes in the military housing market--all of the Army's family housing on Oahu, Hawaii. That contract will involve managing, rehabbing or building about 7,700 homes at Fort Shafter, Schofield Barracks, Tripler Army Medical Center and other sites. The Army Corps of Engineers' Baltimore District is beginning to evaluate initial submissions for minimum qualifications on that multi-hundred-million-dollar project.

"A year and a half ago, I would have said, 'Yes, the business involves mainly three to four companies so far,'" says James J. Rich, chief of the district's contracting division. "I know that number increased with every acquisition cycle and I like to think it's because the industry says these guys are doing it right."

Both the Army and Navy take as long as a year to reach contract closing, which requires approval from Congressional committees. But there is an important difference in the two services' approaches. The Army asks competitors to prepare a more general proposal, and after picking a partner, pays a $350,000 fee for creating a community development and management plan. The housing then is turned over to the partner and the plan becomes part of the ground lease and contracts.

The Navy, in contrast, asks for more information without compensation. It asks short-listed companies to submit a detailed proposal of the development, construction and management plan and uses it to prepare contract documents for closing, but pays nothing for it. The advantage is that everything is ready to go and the partner can start earning money, says Scott Forrest, director of special ventures acquisition for the Naval Facilities Engineering Command. "We complete all the business documents and the design, budget and management agreements," he notes.

What draws companies to these multiyear contracts is the opportunity to tap stable sources of modest profits over long periods of time. "A large project like this creates a steady business stream over a long period and that was attractive," says Frank Codispoti, president of Atkins Benham Constructors, a design-build contractor.

In exchange for rehabbing, building and managing units, the private companies pocket the occupants' basic allowance for housing, a stipend that the military gives each service man or woman. These are determined partly by rank and partly by formulas based on the local real estate market. In 1998, Congress increased the allowance so that uniformed personnel won't have to spend money out of their own pockets to house their families. The 1998 raise provided an unexpected windfall for some partners in the first few privatized housing deals, according to a report issued last June by the U.S. General Accounting Office (ENR 7/8/02 p. 12). Raymond F. DuBois Jr., the top DOD official involved in bases and environment, agrees with most GAO criticisms, but says corrective measures had been taken.

CASH FLOW. Still, the revenue streams are significant. On high-cost Hawaii, where the average annual military housing allowance is $16,000 a year, the revenue stream from the Army's Hawaii family housing is estimated at over $100 million a year, says Patrick Batt, the project's program manager.

How much profit will the Army's partner make? "You want to structure a deal with incentive-based fees and reasonable profits," says Batt.

The Army and Navy say they have refined their selection process, but one executive familiar with each branch's procedure claims it actually has become harder. The Army's process "is getting more unwieldy," says J. Donald Couvillion, executive vice president of development for Equity Residential Properties Trust, a Chicago-based real estate investment trust.

A housing contract at Fort Lewis, near Olympia, Wash., for which EQR Lincoln RCI Southeast was named last April as the designated partner, "was a straight RFP," he says. "We responded, qualified and were selected based on qualifications." After that, detailed construction, development and management plans were made.

Couvillion says the Army selection process now involves a short list for minimal qualifications; a second round to explain the vision, development and financial plan that the proposer has only 40 days to prepare; and then an oral presentation. That adds a step absent in the first round of pilot projects. "They are trying to pin people down a little more," Couvillion says.

NO LUCK. The privatization program has not worked for a number of prospective bidders, even veteran military construction firms such as Hensel Phelps Construction Co., Greeley, Colo., and its development arm, Phelps Program Management. They have tried to win contracts for three years with no luck, says Thomas M. Wierdsma, director of project planning and development.

For another experienced military engineer-contractor, DMJM-H&N, Los Angeles, the market so far "hasn't been a good fit," says Paul D. Steinke, senior executive vice president. "We haven't figured out how to make any money at it." The firm was a member of only one team, which made an unsuccessful submission.

In addition to proposal costs, another risk is housing allowance variance by rank, with officers receiving bigger stipends that translate into higher rental income per unit. "And there is no guarantee on how many officers you could get," Steinke adds. "If you get more privates, say, than master sergeants, you could be in trouble." And, while long-term contracts are appealing, that very length may be problematic to some firms.

Chris Bicho, the chief financial officer of Picerne Military Housing, a Warwick, R.I.-based firm that is a partner with the Army at both Fort Meade, Md., and Fort Bragg, N.C., says contractors and engineers without housing management experience or partners will not be able to do the job. He says Picerne's low-cost housing to be built at Fort Meade will include a four-bedroom apartment that will rent for $1,300 a month, lower than the $2,000 he says that it would cost off-base. And he says only a veteran housing manager such as Picerne can master the operational challenges.

Adds Bicho: "We've got to take care of families. This is not about putting nails in wood."

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment