The "bunker." It is the traditional shell used to house facilities fitted with equipment and infrastructure needed to respond to major emergencies. In the new millennium, the bunker mentality is going out of style.

|

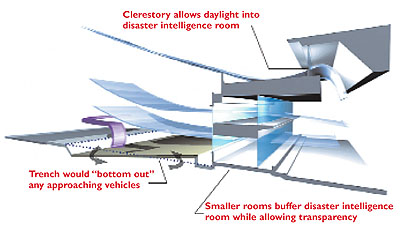

| COMMAND POST When major emergencies occur, field operations are coordinated from the new Office of Emergency Services building (above). A clerestory (left) lets daylight into the otherwise windowless disaster intelligence room. |

The emergency operations center located in the capital of one of the most populous East Coast states is typical of the old school. Constructed as a consequence of the Civil Defense Act, the bunker dates back to the Cold War. It was intended to be used as a second seat of government if the worst imaginable attack occurred.

The 2,250-sq-ft crypt, buried below grade, is protected by 3.5 ft of concrete. It has its own emergency power and air filtration systems. An office building was constructed on top of it.

|

By contrast, California's Office of Emergency Services headquarters in Sacramento is an example of the newest generation of emergency response buildings. Media-savvy government officials realize that presiding over a dangerous situation from a highly visible, above-ground facility broadcasts confidence. Going to the cellar communicates fear. Officials are now, more than ever, choosing to maintain a presence from places that are more likely to allay public fears. The same open, daylight-filled structures also make better work environments for those who bear responsibility for making extremely important and often difficult decisions in very stressful situations.

In Sacramento, the L-shaped complex includes an administrative office building, designed by Dreyfuss & Blackford Architects. This building houses the day-to-day operations of the Office of Emergency Services, and if needed, would also house post-disaster functions. A two-story bridge connects it to a second building, the State Operations Center (SOC), designed by RossDrulisCusenbery Architecture. A third building is a central plant, housing communications equipment, antennas, satellite dishes, boilers, chillers and emergency generators. The complex, on a 12-acre site, is the anchor project for the adaptive reuse of the former Mather Air Force Base.

|

THE STATE OPERATIONS CENTER.

When a multi-jurisdictional emergency occurs, personnel use the SOC's infrastructure to gather and analyze critical intelligence, and to allocate resources to support field and recovery operations. Events where the SOC might be activated include natural disasters, accidents or terrorist events. The complex is equipped with advanced telecommunications, data and audiovisual systems, and dedicated spaces which are used for planning, training, simulations, and actual prolonged response and recovery operations. The facility has media rooms for radio and television broadcasts and press conferences, a 24/7 warning center, telecommunications rooms and a large multipurpose room.

The disaster intelligence room, also called the blue box because of the color of its exterior skin, is the nerve center of the SOC. From it, local, regional, state and federal agencies can be linked to enable them to provide coordinated disaster response. It is amphitheater-like, and workers sit at rows of desks that face large video screens. Break-out rooms surround the command and logistics room, shielding it from exposure to the outside, although clerestories allow a generous amount of daylight to enter the space.

|

SECURITY FEATURES

One solution for keeping openness without sacrificing security involves the use of land forms: a 300-ft-long, gently tilted arc-shaped earthwork that separates the building from adjacent roads. This feature conceals a deep trench and a retaining wall that protect the building from errant drivers. Their vehicles will bottom out if they come too close.

The SOC can operate for almost a week on diesel power, so safeguarding the facility from the damage that could be caused if its fuel tanks caught on fire was an issue. This was one of several considerations that dictated a separation of the physical plant from the other buildings.

The Office of Emergency Services headquarters shows by example how architecture, by being open, can help deliver the message of safety and security. By contrast, a cave of concrete would connote fear.

|

|

The ANTI-BUNKER The latest approach in emergency command centers is to be seen and heard from. The disaster intelligence room (above left) is the nerve center of the state Office of Emergency Services in Sacramento, Calif. The physical plant (far left) is a separate building. A bridge connects administrative office building and operations center. Credits: Rendering © Rossdruliscusenbery Archtiecture; Photos © Mallory Scott Cusenbery, AIA |

PROJECT TEAM

PROJECT: Office of Emergency Services headquarters

CLIENT: State of California

LOCATION: Sacramento

ARCHITECT: (State Operations Center building, lobby, and site:) RossDrulisCusenbery ArchitectureCharles Drulis, AIA, Project Director; Mallory Scott Cusenbery, AIA, design principal; Michael Ross, AIA, consulting principal; Grace Nash, AIA, project manager; Rob Rynearson, Patrick Riley, Gwen Stanley, Gyorgy Varga, Fred Hyer, project team.

ARCHITECT: (Headquarters Office Building, site, and project executive architect) Dreyfuss & BlackfordJohn Webre, AIA, project director; Kristopher K. Barkley, AIA, project architect; Peter Saucerman, Mike Monson, Mike Lee, project team.

CONSULTANTS: Buehler & Buehler (structural); Capital Engineering (mechanical); Alta Consulting Services (electronics)

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment