But this success comes at a price. The traditional clattering, smoke-belching behemoths are heading for the boneyards as clean-air initiatives in the U.S. and abroad push a new generation of cleaner-running, more powerful motors into the marketplace, both on and off the road.

|

| HARD LINE Engine producers are spending billions on research for new engines that meet stringent emissions mandates. (Photo courtesy of Detroit Diesel) |

By 2007, the efforts in the U.S. will reduce overall diesel emissions by more than 75%. "We believe emission standards to be technology forcing," says a top official with the Environmental Protection Agency, who believes that the next decade will require the most progressive fuel and engine refinements of all time. Once that level of success is achieved, "it would be hard for us to make more stringent standards," she says.

"Today's diesel engines are cleaner, quieter and more reliable. In the mid-1980s, they even had half the horsepower and half the torque," says Phil Christman, vice president of product development for International Truck and Engine Co., Warrenville, Ill. Nonetheless, engine manufacturers are feeling pinched to enhance diesel technology while continuing to deliver a cost-effective product. "It is our job to balance public policy and technology, but in reality, the only way we get lower emissions into the marketplace is if people buy it," says John C. Wall, vice president and chief technical officer of Cummins Inc., Columbus, Ind.

|

Changes are hitting fleet owners indirectly, although they agree that economics are a driving force, citing diesel's long history of affordability, performance and power. "I think diesel will get more expensive, but for heavy trucks and equipment, I still don't see any viable alternatives at this point in time," says David Greenlee, fleet manager for Alyeska Pipeline Service Co., Anchorage.

The heart of the diesel-engine problem is the exhaust, which scientists say comprises a doubly poisonous concoction of greenhouse gases and black soot, including nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulfur dioxide, nonmethane hydrocarbons (NMHC) and fine particulate matter (PM). Critics believe these irritants cause heart attacks, lung and bladder cancer, chronic asthma, bronchitis and even hay fever. Children are most sensitive to diesel fumes. "Lungs in children are still developing they also take in more air than adults," says Rochelle Tafolla, director of the American Lung Association of Metropolitan Chicago's diesel cleanup campaign. According to Tafolla, between 20 and 40 children per million develop cancer each year from diesel exposure. She points to an increase in asthma-related symptoms among Americans, with diesel blamed for 300,000 asthma attacks, one million lost workdays and 16,000 premature deaths every year.

Addressing these health concerns is going to be tough over the next few years, as EPA officials say engine manufacturers have produced "no show stoppers at this point" in technol-ogy to meet the 2007 on-highway standard. It will reduce NOx engine emissions to 0.2 g/bhp-hr, fine particulate to 0.01 g/bhp-hr and NMHC to 0.14 g/bhp-hr.

Despite the conflict, Allen Schaeffer, executive director of the Diesel Technology Forum, argues that diesel is "absolutely not" going to disappear. He says exhaust from off-highway vehicles, including equipment, accounts for only 3.3% of all diesel emissions. However, John Walke, director of clean-air programs for the National Resources Defense Council, says that construction machines cause at least 8,000 premature deaths each yearthe same number as on-highway vehicles like tractor-trailers and city buses. "Off-road vehicles are responsible for an inordinate amount of pollution relative to the size and class of equipment out there," says Walke.

Together, EPA and the industry are taking a systems approach, with much recent emphasis on cleaning up diesel fuel before it even enters the engines. Weak off-road regulation has contributed to off-highway fuel harboring sulfur levels as high as 3,500 ppm, compared with a 15-ppm low-sulfur on-highway standard required by January 2007. Refiners expect EPA to launch an advanced notice of rulemaking later this year, with publication next year, that will match up on- and off-road fuel requirements by 2012 (ENR 1/13 p. 11). Current on-highway levels are at 500 ppm.

The National Petrochemical and Refiners Association, Washington, D.C., foresees a major construction challenge for its members in complying with the new regulations. The estimated $8-billion capital program required will occur in a short period of time throughout the refining industry. In addition, the hydro-treaters needed to meet the standard will require at least two new reciprocating compressors, which are made by only five manufacturers worldwide. Only one of them is in the U.S.

And not all refineries have the capability to produce 15-ppm diesel fuel. Utilization percentages for refinery capacity fluctuate between the high 80s and mid-90s, says Bruce Schwartz, director of New York City-based Standard & Poor's Ratings, which, like ENR, is a business unit of the McGraw-Hill Cos. But NPRA has estimated that 10 to 20% of total diesel capacity may simply disappear because refiners cannot justify the economics. NPRA maintains that the market cannot lose that much diesel-production capacity without causing upward pressure on retail prices.

![]() Click here to view chart

Click here to view chart

Engine manufacturers are feeling the crunch, too, as they race to meet upcoming regulations over the next few years. "You don't have to be a rocket scientist to see the trend in emissions reduction," says Tana Utley, director of engineering for Caterpillar Inc's engine center in Mossville, Ill.

"The regulators will always be the driving force behind new emissions technology," adds Tina Vujovich, vice president of environmental policy and marketing for Cummins, which in 1998 entered into a federal consent decree along with Caterpillar, Volvo, Detroit Diesel and Mack to step up their clean- diesel programs. The decree required participants to decrease on-road NOx and NMHC levels to 2.5 g/bhp-hr by October 2002, rather than an original January 2004 deadline. It also pushes up by one year to January 2005 a due date to reduce emissions on off-road equipment by 70% from 1998 levels.

Mechanical engineers are attacking the problem by enhancing fuel delivery, air flow and exhaust after-treatmentbut approaching on- and off-road separately. "Most new technology is coming from the on-highway side of the business, with manufacturers trying to apply it as best as practical to meet off-highway emissions," says George Polson, director of off-highway engine applications for Detroit Diesel.

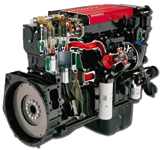

A popular method for cleaning up on-road trucks is cooled exhaust-gas recirculation (EGR), which pushes diesel exhaust back through the combustion chamber where it mixes with ambient air. Engineers say this requires a special EGR cooler, larger radiator, variable-geometry turbocharger and additional valving. Off-road engines are moving toward sophisticated electronic injection. According to Wall, EGR has proven effective for on-road engines because of their duty cycle. EGR works well for highway trucks because they have a constant supply of air as they move down the road but off-road machines do not, he explains. Enhanced fuel delivery is more feasible for off-road applications, he adds.

With engine duty cycle the prime issue in focus, manufacturers have kept contractors involved in the technology debate. "We are concerned about whether the highway engine technology can be readily transferred to off-road machines," says Leah F. Wood, environmental counsel for the Associated General Contractors. "We support the clean-air objective, but we're concerned that if engines are not properly tested and verified in the field, then technology could disrupt power output and ease of maintenance on construction equipment."

|

|

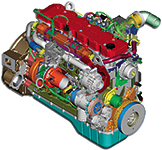

| SMART Several new on-road engines recirculate exhaust gas (above), while off-road engines refine fuel delivery and ignition systems (below). (Renderings courtesy of Cummins Inc.) |

One manufacturer is taking a unique strategy. At the Mid-America Trucking Show in Louisville, Ky., Caterpillar on March 19 will unveil its new on-highway engine, which received EPA certification Jan. 17three months after the October 2002 compliance deadline. Utley says the engines incorporate an "advanced combustion emissions reduction technology," or ACERT, that refines fuel injection, combustion and exhaust after-treatment.

Even though the engines arrived late, costing the company thousands of dollars for each noncompliant unit manufactured in the interim, Caterpillar hopes to step ahead of the competition when regulations get stronger down the road. For October's off-road standard, Caterpillar added electronic fuel-injection controls to its engines. For the 2005 due date, the manufacturer says it will introduce ACERT to the off-road market, including its family of Perkins engines.

"We don't select technology paths that would be discontinuous with the direction regulators are going. We have made this decision consciously knowing that we wanted a technology that we could continue to refine and evolve to meet emissions regulations," Utley says, explaining Caterpillar's rationale for the compliance delay.

Whatever the method, research and development is cutting into profit margins, requiring manufacturers to add labor and materials to their products. As a result, clean-diesel engines will cost more. Utley estimates that Caterpillar will chalk up at least $500 million in R&D for the latest round of mandates and Wall says Cummins this year will spend about $250 million for improvements, including emissions reduction.

This price inflation can translate into increases of up to $5,000 for contractors purchasing new diesel trucks, says Brian Lindgren, vocational-market sales director for Kenworth Truck Co., a division of Paccar Inc., in Kirkland, Wash. Buyers of construction equipment are seeing hikes of 1 to 2% on machines meeting the most recent standard, says Steve Kiskunas, product manager for OmniQuip Textron Inc., a telehandler manufacturer based in Port Washington, Wis. "Fuel economy also is a bit of an unknown until we get more experience with these engines," Greenlee adds.

Of course, these changes also affect equipment buyers, who are more worried about performance, power and serviceability than price. Technicians like Mike Monnot, director of equipment for Zachry Construction Corp., San Antonio, say the newer engines "most assuredly" pose maintenance concerns, such as requiring dealer servicing and calling for more expensive lubricants. In today's economy, now "is not a good time to be raising prices," Kiskunas says.

Complexity aside, experts say one advantage of the newer electronic fuel-injection engines is diagnostic capability. "With electronics, you can catch problems well in advance," according to Polson, who adds that the engines are requiring fewer service intervals.

New engines aside, AGC's Wood says diesel-engine retrofits like particulate traps, though not required, are gaining attention from fleet owners (ENR 4/1/02 p. 11). According to Wood, retrofit programs currently being discussed with EPA will help smaller-sized contractors upgrade older equipment, especially so they can compete for contracts in states where clean-air regulations have affected state funding.

"Our members have been receptive to the concept of retrofitting. It's a hot issue because it is a way for the construction industry to participate in the clean-air process right now," says Wood. "The problem is that there are very few technologies out there readily available, and few states have grant dollars to help pay for the cost."

Ironically, in the beginning, Diesel had greener ideas for his new engine. For example, when a unit performed at the Paris World Exhibition of 1900, it was powered by peanut oil. In a 1912 speech, Diesel prophesied that "the use of vegetable oils for engine fuel may seem insignificant today, but such oils may become, in the course of time, as important as the petroleum and coal-tar products of the present time." It was not until the late 1990s that "biodiesel" fuel started attracting interest as an alternative fuel that can run in existing engines.

Despite the diesel clean-up struggle, fleet owners seem confident about the future. Says Greenlee: "This is a decade of change, but I think diesel will continue to get cleaner, and manufacturers will strive to reduce costs for end-users."

nternal-combustion engines were still novel in 1892, when German engineer Rudolf Diesel filed a patent for a compression-ignition engine running on fuel oil that rivaled contemporary spark-ignition gasoline technology. A little more than a century later, his name is ubiquitous among heavy-duty vehicles worldwide, as diesel engines power 19 out of every 20 construction and utility machines in the field.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment