...but the crew was directed to move on once the Macondo well was converted to readiness for production.

Investigators are studying whether the desire to move on quickly as well as the money saved on the rig’s half-million-dollar daily lease fee governed some of the decisions made and increased the blowout risks.

Those decisions, according to testimony during several different federal investigations, include the use of a long-string design of the well casing, failure to use enough centralizers in the cementing operation, failure to question the cement test or re-test the cement, placing the cement plug far below the seabed and displacing drilling mud with lighter seawater prior to setting the cement plug.

What may never be known is whether more licensed engineers would have opposed any of the changes that added risk—raising the costs to BP.

“What most corporations don’t like is for their employees to have a higher duty [to the public] than to their senior management or to their stockholder’s desire to make a profit,” wrote an engineer who called himself “Deepwater” on theoilddrum.com. “Sometimes the PE laws create a direct conflict with this desire, when management acts in a manner directly counter to the health, safety and welfare of the public.”

The conflict occurs because, under state license laws, the obligations imposed on engineers imply a right to exercise professional conscience.

“Pursuing those responsibilities involves exercising both technical judgment and reasoned moral convictions,” wrote Mike W. Martin and Ronald Schinzinger in their book “Ethics in Engineering” (McGraw-Hill, 1983). “The basic professional right is an entitlement giving one the moral authority to act without interference from others.”

To refuse to cut safety margins presumes an engineer has the technical capability to measure them, too.BP’s Deepwater Horizon well staff had more than on-the-job training. For example, Mark Hafle, the company’s senior drilling engineer for the well, told the joint investigating commission he had a B.S. in petroleum engineering from Marietta College in Ohio. Beyond that, he had no special certification or engineering license. In the hearings, commission members tested his technical knowledge, asking him to define “facture gradient” and “pore pressure.”

Over the long run, the Gulf disaster could speed up second thoughts about licensure and exemption, but a Sisyphean determination will be needed to overcome industry’s opposition. The oil-and-gas industry has sharply criticized the new interim rules requiring an engineering review of aspects of deepwater wells.

One hoped-for outcome is a cohesive NSPE policy on exemptions, something the organization has not addressed since the early 1970s.

Craig Musselman, chairman of NSPE’s Licensure and Qualifications for Practice Committee, says there is significant political influence in places where industries play a strong role in the economy.

The first step, he says, is to get a clearer picture of the licensing landscape by examining industry exemptions across the nation and how each state defines them. He expects there will be clear industrial exemptions in some states, while other states may have “veiled” industrial exemptions.

In the short run, engineers may recognize in the Gulf disaster some troubling parallels to building construction, where partly developed plans are changed again and again and all the changes may never be evaluated from a distance. For both the licensed and unlicensed, the Gulf disaster sends a clear message about unforeseen risk.

| The following are some of the individual design and operation decisions, some of which were approved by federal officials, that helped cut costs prior to the April 20 Macondo well blowout, explosion and Gulf spill. |

|---|---|

|

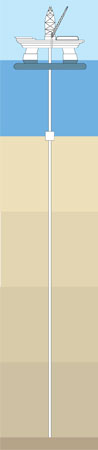

LONG-STRING WELL DESIGN A BP plan review prepared in mid-April recommended against the full string of casing from the top of the wellhead to the well bottom in favor of one that would have provided more barriers to gas flow. Long-string casing saved $7 million to $10 million and time. | |

|

CENTRALIZERS Instead of the 21 “centralizers” recommended by Halliburton, BP used only six to center the pipe in the well bore to ensure that casing cement flowed evenly around the pipe. Halliburton warned about losing control of gas, but BP declined and saved 10 hours of work. | |

|

CEMENT BOND LOG Wells are generally filled with weighted mud during the drilling process, but that process at the Macondo well could have taken up to 12 hours and cost more than $128,000. | |

|

MUD CIRCULATION BP replaced the drilling mud at the bottom of the well with less heavy seawater before commencing the cementing process, even though the American Petroleum Institute recommends using fully circulating drilling mud. That operation could have taken up to 12 hours. | |

|

LOCKDOWN SLEEVE BP decided not to install a critical apparatus to lock the wellhead and the casing in the seal assembly at the seafloor. Known as a casing hanger lockdown sleeve, the apparatus prevents the casing from becoming buoyant, giving fluids a chance to break through. | |

| Source: HOUSE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE; FEDERAL HEARINGS. | |

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment