The Odebrecht Organization awarded its first annual Odebrecht Award for Sustainable Development in the United States in October. A team from Houston’s Rice University brought home first place for their solution for oil companies venturing further offshore – an island constructed for workers to live on while working deep sea oil fields.

Established in 2008 in Brazil, where Odebrecht is located, the award provides students with the chance to present new ideas, as “engineering is a powerful force for positive change.” Since its establishment, the Odebrecht Award has expanded to Angola, Argentina, the Dominican Republic, Panama, Peru, Venezuela and the United States.

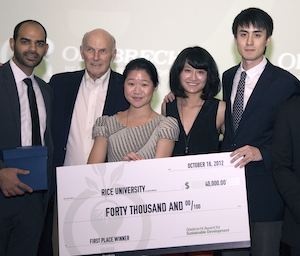

Rice University architectural students Joanna Luo, Wejia Song and Alexander Yuen, and their advising professor Neeraj Bhatia, took home the $40,000 first place prize for their project, “Addressing the Logistical Crisis of Offshore Oil Extraction: A New Model of Water-Based Urbanism in the Pre-Salt Region off the Southeast Coast of Brazil.”

The whole idea is propelled by an initiative by Brazilian enery major Petrobras “to move oil workers into islands out at sea as opposed to shuttling them back and forth between the mainland because in this region off the coast of Brazil, the oil that’s being discovered or that’s now available, is getting further and further away from shore, so it’s getting less feasible to get people out there,” Yuen says.

The project details the creation of a 600-km long chain of man-made islands, amid a cluster of deep-sea oil rigs, capable of sustaining a population of around 50,000 workers. Furthermore, the system relies on pipelines rather than shuttle tankers to transfer oil back to shore. The islands would be self-sufficient to the point of being able to raise crops, build schools and drill oil, making the oil recovery process more environmentally, socially and financially sustainable.

“The project itself emerges from a larger project, even bigger than Rice University, called the South America Project, SAP, and this is a project spearheaded by Harvard’s Graduate School of Design in cooperation with 12 schools in South America and three schools in North America, essentially to engage disciplines with design backgrounds into issues of infrastructural development in South America,” Bhatia says. “It piggybacks off several initiatives being developed off of IIRSA’s [Initiative for Infrastructure Integration of the Region in South America] agenda. It’s essentially a policy between 12 countries that has forecasted large amounts of infrastructure to be built. The reasons these 15 schools are involved in these questions of infrastructure from a design standpoint is really to gauge social and environmental questions around sustainability into the question of design, and this is where the agenda of the studio aligned itself with the Odebrecht call, which defined sustainability in a very complex way, and really tries to reconcile politics, economics, social issues, cultural issues as well as the environmental sustainability that we often think about and how you find a balance between these things.”

Yuen says the most difficult part of the project was the undefined nature of the territory they were navigating, an ambiguous territory between engineering and urbanism and architecture.

“It wasn’t architecture, it wasn’t engineering – we’re not engineers, we’re trying to be architects – trying to find something that was progressive and brought new ideas to the table without sounding too naïve or digressing too far from one area. So we didn’t want to propose something that an engineer would look at as hogwash and we didn’t want to propose something that an architect would look at and say, ‘well this isn’t architecture.’ It was trying to find that middle ground, that nice comfy zone, a constant state of back and forth between research and design across a wide range of scale too,” Yuen says.

In addition to winning the top prize of $40,000 (of which the students receive $20,000, their advising professor receives $10,000 and their university receives $10,000), the winning team of students receive admission to the process to become an Odebrecht Young Partner or Braskem Associate, trainee programs with the global leaders – highly competitive programs sought by students from across the globe.

A total of 422 students competed for the award, representing 40 nationalities and 173 universities across the United States.

A team from Johns Hopkins University took second place and third place went to North Carolina State University.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment