Home » Keywords: » Lead and Copper Rule

Items Tagged with 'Lead and Copper Rule'

ARTICLES

Drinking Water

Lead and Copper Rule improvements would require all lead lines replaced over next decade

Read More

Engineering Ethics

Clean Water Warrior Wins 2017 ENR Award of Excellence

How Marc Edwards used engineering skill to expose lead levels in Flint drinking water

Read More

After Flint, Michigan Pushes State Lead Rules Beyond Federal

Following the Flint crisis, Gov. Rick Snyder proposes a state-level overhaul with stricter standards than federal guidelines

Read More

Lead Poisoning

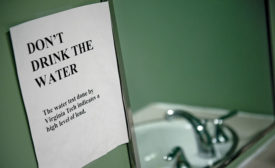

Crisis in Flint Underscores a National Drinking Water Quality Problem

Awareness grows of trouble in other drinking-water systems across the U.S.

Read More

Outrage Mounts Over Flint Water Contamination

Construction and water leaders say crisis underscores national problems with lead contamination of drinking-water supplies

Read More

The latest news and information

#1 Source for Construction News, Data, Rankings, Analysis, and Commentary

JOIN ENR UNLIMITEDCopyright ©2024. All Rights Reserved BNP Media.

Design, CMS, Hosting & Web Development :: ePublishing