... consultant McKinsey & Co. (with whom Suffolk has no relationship). “There are a few of them, people who are very talented and can stretch and grow. They are the exception, not the rule.”

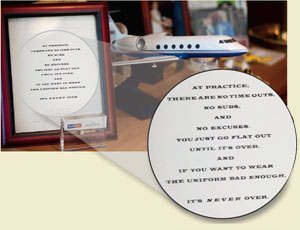

John fish’s Daily inspiration Fish’s office contains a framed statement about commitment and hard work in athletics that he obviously applies at Suffolk, where people start the day very early and the firm’s cafeteria and gym seem to invite the staff to stay and stay. Fish says he wakes up on some weekdays at 3:30 A.M. People in the industry say he calls them at 6:30 A.M.

‘Fear of Not Succeeding’

It’s 1972, and 12-year-old John Fish is hunched over his desk at Hingham Junior High in Massachusetts, trying to make sense of his spelling book. “I’m nervous. I’m short of breath. My hands are sweating, and I’m praying I won’t be called to the blackboard,” he recalls. “I want to participate, but … there’s something that’s confusing those words in my spelling book.”

In those days, most teachers had not heard of dyslexia and assumed a student was slow, lazy or just stupid. This produced in Fish a “fear of not succeeding,” he recalled in a 2004 speech at his college alma mater, Bowdoin College.

Journalist Malcolm Gladwell has a theory that dyslexics compensate for their handicap with improved social skills. Those “compensatory skills [give] them an enormous head start,” Gladwell wrote in The New Yorker.

Fish remembers the extra-long hours he needed to study at Bowdoin—and sports. At one point, he says, he put on 80 lb., mostly through weight training, in order to play on the Bowdoin football team’s offensive line. Sports, Fish says, gave him a way to develop confidence.

When Fish graduated from college, his father put him in charge of operations at the newly formed Suffolk and mentored him. Building small projects in the Boston suburb and underbidding union contractors by 10% to 15%, the company slowly grew beyond its humble start.

A turning point came in 1984, when Suffolk won a key project at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass. But that job and others Suffolk won helped put the firm on a collision course with the carpenters’ union, which was wary of a rising open-shop competitor to the signatory union contractors. The union started a corporate campaign against Suffolk, including sending picketers to Fish’s home, an experience Fish describes as “hell.” In 1993, Fish finally realized that to work in downtown Boston, he couldn’t fight the carpenters. He “came to an understanding,” in Fish’s words, which allowed Suffolk to work union in downtown Boston, paying union-scale wages and benefits, but still working open shop elsewhere in New England.

The arrangement gave Fish an advantage that rankled other building contractors who worked union throughout New England. But five years later, all contractors, including Suffolk Construction, agreed to work on the same basis under agreements with the carpenters’ union throughout New England.

Fish’s relationship with the New England carpenters now is good enough that Suffolk served last year as general contractor for the union’s new, $19-million headquarters in Boston’s Dorchester section.

The majority of Suffolk’s work around the country remains open shop. The firm works as an at-risk contractor, stipulated-price construction manager or design-builder but never as an owner’s project manager for a fee, says Mark. L. DiNapoli, president and general manager of Suffolk’s northeast region. DiNapoli led Suffolk into complex renovations and additions, a field in which it now excels, and was one of the core executives who took more responsibility when, in 2004, the company rearranged duties among its top managers so that every project manager was no longer reporting directly to Fish.

Territorial expansion outside New England started in 1989, when a customer asked Suffolk to build an assisted-living and medical-office project in the Palm Beach, Fla., area. That went well, but Suffolk ran into difficulties that Fish attributes to regional differences in doing business. The answer was to hire local talent, particularly Rex Kirby, a University of Florida engineering graduate who was working for Suitt Construction Co. in Orlando.

Kirby, now 53, called himself Suffolk’s “token Southerner” at the time but says he fits in easily with the fast-talking New Englanders. The Florida operations’ volume peaked in 2009 at about $390 million. High-rise residential work has dried up, so Kirby is winning jobs out of state, including a Navy data center in Charleston, S.C.

Suffolk employees and observors describe the firm as entrepreneurial and aggressive, but it doesn’t always win just on price. Suffolk bested joint ventures that included Balfour Beatty and Turner for the at-risk construction manager’s job for parking structures for the new Florida Marlins ballpark in Miami. While Suffolk’s proposed price wasn’t the lowest—a $6.35 million fee for $75 million of construction—city manager Pete Hernandez wrote that the firm is highly competent and understands the complexity of sharing the site with other contractors.

Another expansion came in 1999, when Suffolk followed client Sunrise Assisted Living Inc., McLean, Va., to a project in San Mateo, Calif. Now based in Irvine and San Diego, Suffolk’s California operations bring in about $175 million a year in revenue.

In some key ways Fish fits what Collins’ describes as the vital “level 5” leader, who can guide a company from good to great. He describes such leaders as fanatically driven, hardworking, longtime employees or owner family members. They also are humble and have an understated manner, says Collins.

Some who have seen John Fish in action say he’s forceful, outspoken and driven to be the “alpha contractor.”

While admitting to being brash when he was starting out in his late 20s, Fish now espouses a more moderate style.

‘It’s Never Over’

But it’s hard to escape a reputation in the Boston area for being hard on subcontractors. After completing the $136.5-million renovation of a downtown Boston federal courthouse and post office last year, two subcontractors have filed Miller Act lawsuits in federal district court in Boston to recover money they claim Suffolk owes them. One of the companies, HVAC subcontractor N.B. Kenney Co., Devens, Mass., claims that plan omissions, changes and delays entitle it to $9.2 million. An online news account of the lawsuits in the Boston Herald in late April provoked several angry comments against the firm, including some who identified themselves as subcontractors.

Fish diplomatically says Kenney had to preserve its payment rights. Further, “This is normal and customary, and I can assure you it will be settled and won’t end up in protracted litigation,” he says.

Of course, there are a lot of subs with axes to grind with big general building contractors. Maybe, but Fish doesn’t like being thought of as just a contractor, with its connotations of people “who ride around in a pickup truck with bricks in the back,” he says.

He would prefer Suffolk be known as one of the country’s great corporations.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment