Alternative project delivery methods (APD) are coming of age among California public agencies. Progressive design-build (PDB) and construction manager at risk (CMAR) were hot topics at the Western Winter Workshop, held March 1-2 in Indian Wells, Calif.

While design-build has been a default method for San Diego County, “CMAR is gaining traction” for vertical and maintenance work, said Marko Medved, director of general services. However, job-order contracting is still the norm for maintenance, he added.

Brandon Dekker, principal with CannonDesign, noted SB-706, a California bill which extends public agency authority to use progressive design-build to 2030. He predicted that 47% of capital projects in the West will use PDB by 2025, and that 85% of all projects will be delivered using alternative project delivery by 2025.

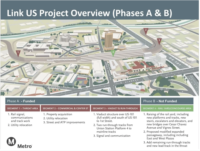

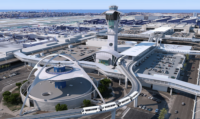

Many panelists discussed lessons learned in the past few years regarding APD. “I wish we had more breathing room” between 30% and 60% design phases for the G Line Improvements Project, being delivered with PDB, said Annalisa Murphy, senior director with Los Angeles Metro. “We needed time to react to the [cost] estimate we received.” The agency ultimately utilized value engineering ideas to reduce costs, although “a bit at the expense of the schedule,” she said. With such risks as using a new technology for railroad gates and interfacing with another project, “PDB was the perfect option,” she said.

James Wei, deputy executive officer of project management with Metro, said that using the construction manager-general contractor method brings cost estimating and risk management together to “flesh out who can best manage risks.” For a toll-lane project, Metro took on certain risks because even if it had put them on the contracting team, ultimately “we have to pay either way.”

Gregory Gastelum, Metro senior executive officer, said that 15 formal groups of experts specializing in topics such as independent cost estimating, utilities and trackwork regularly meet for the East San Fernando Valley Light Rail project, which is utilizing PDB. “Don’t be afraid to throw [forth] anything you think could benefit the project,” he said. “A risk matrix is built up, and we build on it throughout construction.”

CMAR Lessons

Bill Canterbury, president of Canterbury Construction Management Services, noted that CMAR tends to entail more self-performed work on heavy civil projects. He cautioned that a well-written Request for Proposals is key: “A poorly written RFP equals a poor CMAR project.” If an owner has unreasonable schedule expectations, he added, contractors won’t bother, as there is plenty of other work.

“Make sure the RFP defines what [the engineer and contractor] need to do at each stage of design,” he said. Since the owner still controls the design, “you don’t want the engineer to be complacent, or the contractor mailing in estimates.”

A guaranteed maximum price should not be based on preconstruction services, or on early design, he added. On the other hand, 60% design “is too late to bring in a CMAR team.” A lump-sum GMP is preferable to cost plus fee, he said, because in the latter, “owners have to hire someone to verify costs each month. It’s not fun.”

Off-ramps—where the owner can opt out of a contract with a CMAR team—should be considered a last-ditch resort, he cautioned. “CMAR is a good-faith effort by three key stakeholders, not two as in design-build,” he said. Casually turning to an off-ramp destroys that good faith, he noted.

Such good faith extends to all parties meeting in person and getting to know each other, said Rick Krebs, owner of Krebs Corp., a contractor. “Get to know the person across the table, and believe in the APD process,” he said. “Then it’s more difficult to be harsh. Give it a chance to find out why there’s a discrepancy. Throw stuff against the wall—some of it may stick.”

That said, not all changes may be worth it,” he added. “Don’t save $100,000 but spend $300,000 in associated cost.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment