A proposal to build a project to capture water in California's Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta during wet weather and make it available in drier areas is advancing as state officials anticipate losing 10% of its water supply by 2040 as a result of hotter temperatures.

State officials released a final environmental impact report Dec. 8 for the proposed Delta Conveyance Project that will channel delta water 45 miles south through a tunnel to make it available to other regions of the state, from the Bay Area to southern California.

The preferred design alternative highlighted in the report is reduced in scope compared to other considered options as a result of feedback, according to the California Dept. of Water Resources. But it is still planned to yield about 500,000 acre-ft of water per year, enough to serve about 5.2 million people.

Even if it receives a state OK, the project has various other regulatory approvals it would need before moving forward to construction. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the lead agency for a federal environmental review, released its draft environmental impact statement about a year ago. The state water agency is expected to work with the Corps on a final report next year. The agency also must submit a change petition to request the California State Water Resources Control Board to allow it to add a point of diversion.

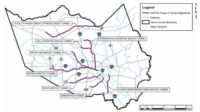

The preferred design would feature two intakes, each with a capacity of 3,000 cu ft per second, along the Sacramento River in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Estuary. One would be located just north of Hood, Calif., and the other between Hood and Courtland. Water would travel 44.6 miles to the Bethany Reservoir near Livermore, Calif., via a 36-ft-interior-dia tunnel located 140 ft to 170 ft underground.

The project would also include construction of a pumping plant and surge basin, aqueduct and discharge structure at the reservoir.

State officials pointed to severe storms that have punctuated otherwise unusually dry weather over the past several years. If there had been an additional diversion point when atmospheric rivers brought heavy rain that caused flooding in parts of California last January, the state could have captured an additional 220,000 acre-ft of water for future use, Carrie Buckman, an environmental program manager at the state water agency, told reporters.

“With the Delta Conveyance Project, we will be able to capture more water in the limited periods that it’s going to be available as we move into the future,” she said. “That additional supply will help stabilize the overall supply of the state water project.”

Water resources department officials could sign off on the plan this month if they find it is in compliance with the California Environmental Quality Act. But the plan has seen controversy over expected construction impacts from people along the potential project area as well as from those living in the northern delta area who say the plan would do nothing to help their water quality. Earlier this year, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency said it was investigating an administrative complaint brought by two tribes, a local Filipino community group and two environmental groups accusing the state of environmental racism.

The state water agency says it received more than 7,000 comments from the public after releasing a draft environmental impact report last year.

The preferred design was selected partly in response to criticism of the plan. It would include just one tunnel with a 6,000 cfs capacity, rather than two with a capacity as high as 9,000 cfs as had been considered. It has the smallest permanent surface area footprint of all the considered alternatives—1,328 acres. The preferred design features a more eastern tunnel route than other alternatives, which agency Director Karla Nemeth says would reduce impacts compared to a route that would have gone through a more central part of the delta.

The preferred design “is significantly smaller and fits in as a complement to significant investments the state has made together with the federal government in local water infrastructure, but also does important things to remove long duration construction impacts and also does more in terms of the potential community benefits associated with this project,” she says.

The reduced scope appears to not have convinced opponents of the project. In a statement after the state water agency released its final environmental report, Sierra Club California said it remains “strongly opposed” to the plan. Erin Woolley, a group senior policy strategist, said the project would be “a costly environmental disaster.” Sierra Club estimated that, accounting for inflation, the project would cost as much as $56 billion. State officials most recent released cost estimate was $16 million in 2020.

“The delta tunnel’s final environmental impact report shows that the [state] has widely ignored concerns raised by environmentalists, tribal representatives and local communities opposing the tunnel’s construction and operation,” Woolley said in a statement.

Not all the feedback has been negative. Adel Hagekhalil, general manager of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, a cooperative of agencies and utilities providing water for 19 million people in six counties, called the plan “part of a balanced, holistic solution” to challenges raised by droughts.

“Metropolitan is taking steps to reduce its reliance on the delta, through increased conservation, water recycling and storage,” Hagekhalil said in a statement. “Still, the water imported through the state water project will always be an essential component of Southern California’s supply.