Combining context-sensitive designs, pre-fabrication, advanced technology and future-proofing, Miami-Dade’s first Bus Rapid Transit project is rolling toward completion despite pandemic- and fiber optic cable-related hurdles. The 20-mile South Dade TransitWay will cut travel times by as much as 30 minutes and increase efficiency along a busy and rapidly growing corridor south of Miami.

OHLA USA has been leading the design-build project since April 2020, when Miami-Dade County awarded the more than $368-million project to the firm for the construction of 14 bus stations—one of which is a a five-level, roughly 645-space park-and-ride garage—rehabilitation of 32 bus stops and improvements to 46 intersections.

The stations will provide an express service that only stops at those stations; another local route will hit all stops along the line, explains Miguel Torres, rail project manager for HNTB, which Miami-Dade County Dept. of Transportation and Public Works hired to provide construction, engineering and inspection services. As the first of the county’s six “Smart Program” rapid transit corridors under construction, the BRT line will connect Pinecrest, Palmetto Bay, Cutler Bay, Homestead and Florida City.

Prefabrication helped achieve the distinctive “bean” shapes of the stations.

Photo courtesy MIami-Dade Dept. of Transportation and Public Works

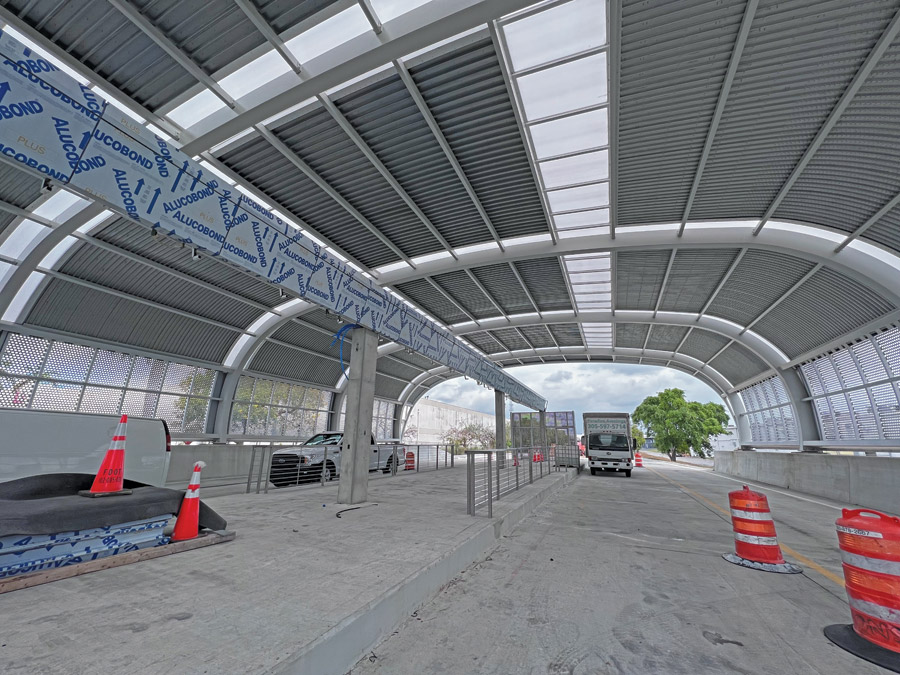

Designs of the new stations went beyond a bench on the sidewalk. “In Miami, they have a very unique design for their transit,” Torres says. “It’s always a dome shape, or a concave like a tube … and it’s a unique symbol to Miami, so if you see that type of structure, it stands out in areas where everything is vertical and everything is a square box.”

Beyond the standout design, the stations will feature air-conditioned vestibules where riders can purchase bus passes and escape the South Florida heat. There will also be screens tracking bus arrival and departure times.

“It’s almost like you’re at an airport,” Torres says. “You’re going to have big screens, you’re going to be able to see the bus arrival, where you need to go to get the bus, how soon the bus is going to get there.”

Prefabrication has been used extensively across the construction of the stations, says Yonathan Benarroch, senior operations manager with OHLA. That includes the interior lighted pylons that will feature the names of each station. Prefabrication was also key in achieving the iconic looks of the stations, with 200-ft-long steel support beams sent to Chicago to be specially bent into the desired curved “bean” shape, he says.

The initial concept from Miami-Dade was to achieve that shape in concrete, but that presented two problems, Benarroch says. First, keeping up with the concrete formwork to create the shape would’ve been “a nightmare” to manage while traffic continued to travel underneath. The second problem was that a concrete structure would have resulted in a semicircular shape rather than the oval-like shape achieved with the steel.

“That shape of the arcs was very difficult to achieve,” Benarroch says, explaining that the beams were bent into shape with special machines. The actual installation was simpler, and the result is a sleeker, more iconic design and profile.

Each station will have real-time information about bus arrivals.

Photo courtesy MIami-Dade Dept. of Transportation and Public Works

High-tech Headaches

First among the project’s challenges is the tight schedule, says Benarroch. Miami-Dade Dept. of Transportation and Public Works (DTPW) gave the design-builder 800 days to design and complete the project, with one of the 14 new stations being a parking garage with a built-in bus station.

Another is the number of agencies involved in the project and the resulting approval processes. Sometimes, he says, submitting the same design to different agencies resulted in conflicting feedback, requiring effective coordination to resolve. At the same time, the project team navigated a complicated technology package for the county’s first-ever bus rapid transit project.

“That is tough,” Benarroch says. “Getting everybody on board to do those types of technologies, software implementation testing—it becomes very, very challenging.”

“It is expected that within a half-mile of the corridor, population will grow by 68% and employment will grow by 47% by the year 2040.”

—Luis Espinoza, Communications and Special Project Manager, Miami-Dade County Dept. of Transportation and Public Works

Extensive coordination and an experienced project team that’s used to a high-pressure environment who can quickly propose and execute on ideas and changes are essential in overcoming those challenges, he says.

The project’s largest hurdle was obtaining 20 miles of upgraded fiber optic cables with the capacity to accommodate not only the new BRT route, but also additional capacity for future expansion, says Alex Barrios, assistant director construction for DTPW.

“The lead time on that during the pandemic became over a year for us to get the fiber, and then it pushes all the installation of all the auxiliary devices, the networks and everything else,” he says.

There have been similar issues with concrete and steel as well as skilled labor, but the delay on the fiber optic cable set the project back a full year to a new substantial completion date of June 2024.

In the design phase, it became evident to the county that the change to a larger cable and cyclical connection model could keep the system up and running if one station was down, an easy way for the county to get a meaningful improvement on the final product, Benarroch says.

That upgraded cable, which is being installed underground in conduits with other infrastructure along the entire 20-mile route, serves as the communications backbone for the whole route, he says, allowing for communication between all stations and all intersections as well as their connection to central control.

All of that had to be factored into the cascading schedule for what’s essentially 14 separate construction projects. Benarroch says teams have to be managed so that when one type of work is completing in one location, it can start in another.

The BRT alignment can be converted to rail service in the future if needed.

Photo courtesy MIami-Dade Dept. of Transportation and Public Works

Built for Buses, Ready for Rail

Each year, roughly 3.6 million residents board Miami-Dade Transitway buses on a route that travels along the South Dade Corridor, says Luis Espinoza, communications and special projects administrator for DTPW.

Around 91,000 people live within a half-mile of the corridor, where about 65,000 work. The corridor of SR 5/US-1/South Dixie Highway has reached its limit for widening at six lanes, he says, along which the northern portion sees some of the worst traffic congestion and travel times for residents in the area.

“The county, along with several municipalities along the corridor, have undertaken several efforts to intensify development along the corridor to create dense, walkable and mixed-use environments in the future,” Espinoza says. “It is expected that within a half-mile of the corridor, population will grow by 68% and employment will grow by 47% by the year 2040.”

“Ultimately, if this grows, we will have everything set to convert it to rail.... All we need to do is put the rails in and put the train on it.”

—Miguel Torres, Rail Project Manager, HNTB

Urban properties respond positively to transportation improvements, he says, and DTPW sees this one as a catalyst for more housing, retail and office developments near the corridor’s transit stations. Espinoza says that the BRT vehicles will be emissions-free and that the corridor is critical in terms of hurricane evacuation and as a post-disaster recovery route.

Ultimately, if the demand is there, Miami-Dade County plans to transition the corridor into a rail line to accommodate many more passengers, which is why Torres is working on his first bus project.

The typical bus is limited to 75-100 passengers, while trains can connect multiple cars and move hundreds of people, Torres says.

None of that infrastructure will be impacted if and when the switch to rail happens, says Barrios, who believes it’s only a matter of time as the South Dade area and ridership continue to grow.

“Ultimately, if this thing grows, we will have everything set to convert it to rail,” Torres says. “Because everything is there. All we need to do is put the rails in and put the train on it.”

That’s why a rail manager is spearheading the bus rapid transit project, he says, because it’s a bus route, but a train-like system: “A dedicated 20-mile corridor that is specific for bus-only transit.”

The bus lane, like train tracks, is in a dedicated alignment. The new stations along that route are constructed just like a train station, with 100-ft-long level-boarding platforms on either side of four lanes of bus traffic.

Along the whole corridor, buses will be able to pass 46 intersections like a train, as safety arms will drop and traffic lights will coordinate to allow the bus to move seamlessly through, Torres says. “When the bus approaches the intersection, they’re going to have what we call preemption,” he says. “There’s going to be some notifications from the bus to the intersection to say, ‘Hey, I’m approaching you, I’m going 45 miles an hour, so I should be crossing your intersection within the next five minutes.’”

Express stations along the 20-mile route will have 100-ft-long level boarding platforms.

Photo courtesy MIami-Dade Dept. of Transportation and Public Works

A countdown will begin, and when the bus is within 1,000 ft, the gate arms will drop and the bus will drive through the intersection without having to stop as would a bus on a traditional route.

The corridor was initially constructed as a freight rail right-of-way, but around 20 years ago as train numbers dwindled, it was first converted to roadway for a normal bus route, Torres says. While construction activity on the project doesn’t include building a new road through the county, it does include some road work to upgrade intersections and accommodate infrastructure for the system’s technological equipment, which Benarroch says is “another multitude of mini-projects.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment