Inflation and supply chain snarls continue to aggravate risks of construction project cost overruns, claims and defaults—and the answers aren't cookbook simple.

"Will there be a serious diesel fuel shortage?" asked one audience member at the International Risk Management Institute Construction Risk Conference on Nov. 14 in Las Vegas, to a keynote presenter.

“I don’t know,” replied Chris Daum, CEO of consultant FMI Corp., from the stage.

Two days later, as if to answer, diesel prices hit $5.35 per gallon—up about 50% for the year as stockpiles dwindled.

The magnitude of the risk-control challenges lent new gravity to IRMI's first fully-attended in-person post-pandemic construction risk event.

A construction recession has already started, Daum and many in the audience agreed. Statistics, never in short supply at the conference, were especially bracing for what they showed about the risk climate.

Cheri Hanes, subcontractor default insurance risk engineering leader at insurer AXA XL, had two of the most worrying sets of numbers in her presentation on strategies for supply chain and cost escalation management.

One that used U.S. Labor Dept. data showed year-over-year changes in the producer price index for new nonresidential construction. Hanes said the bid price index had grown 1.8% in the year leading up to September 2020—but In the year leading up to June 2022, that growth was 19.8%.

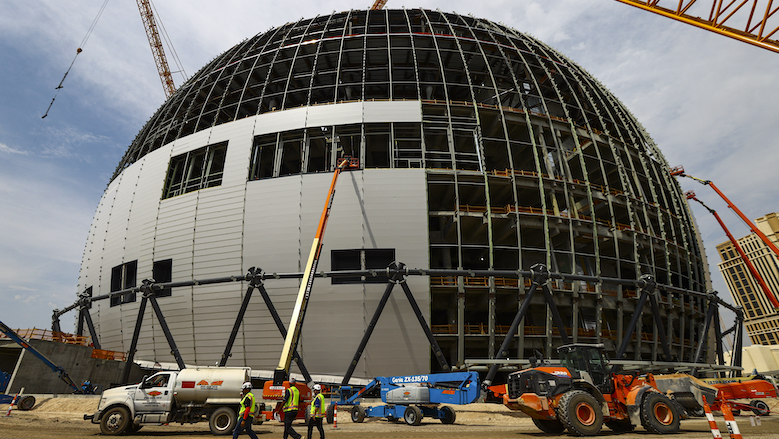

Driving home the point was a recent financial report from Madison Square Garden Corp. that blamed inflation, supply chain and project complexity for adding $175 million to the previous $2-billion estimated all-inclusive design, construction and technology cost of the MSG Sphere project in Las Vegas. Located at The Venetian resort, about one-half mile from the IRMI conference on the Las Vegas Blvd. "Strip," the sphere's construction cost alone now is $1.78 billion.

Even more worrying were Hanes' numbers showing how long it was taking for purchased materials to arrive at jobsites and assembly yards.

Prestressed concrete products that had needed three to four months for delivery pre-COVID-19 now need six to seven. Fabricated structural steel that could de delivered in six to eight weeks now is taking five to six months. Flat glass that used to be on site in three to four weeks now isn't arriving until eight to 16 weeks—and the list went on.

COVID-19 Revealed Risks

While COVID-19 did not increase all risks, it did reveal many that already were present, said Hanes. What were previously considered minor project elements, such as paint colors and door handles, now are holding up work completion.

Subcontractors have not reached the point where they are pricing work and scheduling accurately, she said. "We have to get subs in the same place as general contractors, where they say, 'no, I can't do that for you and can't do it for that price.'"

Added Hanes: "That means we have to manage it differently. If we don't evolve right now, you will get left behind."

Instability is evident in some subcontractor balance sheets, she warned—and with pandemic emergency Paycheck Protection Program funding now gone, it appears that the federal monies may have pushed some potentially deeper financial issues down the road.

Whatever else, vigilance is needed in judging subcontractors, Hanes said. "Trust your prequalification—don't let it be circumvented," she advised, also advising attendees not to make exceptions for some subs in the prequalification process.

Said Hanes: "This is not the time to do it."

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment