On a cold, rainy payday in December 2019, Willy Cicchese—a labor foreperson for Dimeo Construction Co.—realized nobody had seen one of his workers for an hour and a half on a jobsite in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston.

When the worker’s cell phone went unanswered, Cicchese bolted off the more than 250,000-sq-ft residential building project and found the worker a few blocks away sitting in his running car with the windows fogged. Cicchese pounded on the window to no avail, opened the door, grabbed the worker’s shoulder and screamed his name, only to notice the worker gagging, his eyes pinned at 12 o’clock. Cicchese called 911.

Responders twice administered naloxone HCI nasal spray—known as Narcan—to successfully revive the worker. Although a former EMT, Cicchese says he “never witnessed anybody in that condition. I didn’t know if it was a diabetic reaction … I had no clue it was an overdose.”

Providence, R.I.-based Dimeo never considered keeping Narcan rescue kits on the job before the overdose. While the medication is designed to help reverse in minutes the effects of an opioid overdose, Bob Kunz, firm corporate safety director, worried about legal ramifications. “Why should we train, why should we provide it and expect our employees are going to be there to respond?” he asked. “It seemed like a big ask.”

But Dimeo committed to Narcan after the overdose—and it didn’t just place treatment kits on jobsites and walk away. The firm required training for superintendents, project managers and safety managers not just on how to administer Narcan, but also on overdose response and prevention of injuries that can lead to addiction.

Photo courtesy of Gilbane Building Co.

As fentanyl overdoses reach record highs, Dimeo is among a growing number of contractors across North America realizing it is increasingly difficult not to consider placing Narcan on their jobs to help workers who often overdose on prescribed opioids after a jobsite injury.

The Center for Construction Research and Training, a nonprofit arm of the building trades and a National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health partner, recently found “the higher frequency of greater severity injuries in construction as a contributing factor in the higher prescribed opioid.” The center said “the quantity of opioids prescribed to injured construction workers is more than double the average number prescribed in all other industry groups.” It added that those “claimants, on average, receive both 20% more opioid prescriptions and that opioid prescriptions that are 20% stronger.”

While industry officials cite studies illuminating construction’s direct correlation to opioid misuse—including a 2021 study by the Massachusetts Dept. of Public Health showing construction workers are six times more likely to become addicted to or die from opioid use disorders than workers in other industries—efforts to expand Narcan use in construction remains controversial.

Many contractors believe just placing it on construction sites is a liability or creates the perception that drug addicts are on their sites. Smaller employers worry that their budgets can’t afford the resources needed for Narcan training and prevention programs or to hire a third-party provider to place the life-saving drug on their sites.

For now, Dimeo remains among a group of contractors committed to keeping Narcan on hand. “I never want to be in a position where I’m running a program and I haven’t given the workers every tool they need,” Kunz says.

Former Boston Mayor Martin J. Walsh (center), now U.S. Labor Secretary, participated in a stand down in 2019 in memory of workers who died of opioid overdoses.

Photo by Scott Eisen, courtesy of the Building Trades Employers' Association

Data Void

During speaking engagements at construction safety conferences, not many hands go up, Cal Beyer, vice president of Workforce Risk and Worker Well Being at CSDZ in Minneapolis, Minn., says, when he asks groups of construction professionals if Narcan is on their jobsites. When asking the same question using “anonymous polling software,” typically just a few organizations say they deploy the drug kits to their jobsites, adds the vice president of workforce risk and worker wellbeing at CSDZ, a longtime advocate for mental wellbeing in the construction industry.

The absence of a national database or tracking system by the Associated General Contractors (AGC), labor unions or other organizations indicating how many contractors provide Narcan on construction sites makes it hard to know how prevalent it is industry-wide. “We don’t have a national policy or standard practice on the use of Narcan on jobsites,” an AGC spokeswoman says.

While national figures are fuzzy, a variety of experts interviewed by ENR agree that Narcan is available at 50% of jobsites in the Northeast and in other areas where overdoses and opioid use is more prevalent, such as in West Virginia. North of the U.S., Canadian lawmakers introduced legislation that would require Narcan kits in high-risk workplaces, which one expert says “targets” construction. Ontario construction workers accounted for nearly one in 13 opioid toxicity deaths from July 2017 to the end of 2020, government statistics say.

Todd Mustard, vice president of the Association of Union Constructors (TAUC) believes Narcan is more common on larger projects, such as the $6-billion Shell ethane cracker plant nearing completion outside Pittsburgh. “It is less likely to be used by smaller contractors for quick turnaround projects,” he says. Mustard adds that states such as West Virginia, Pennsylvania and California, set to receive large payouts from settlements with “big pharma” opioid manufacturers, are more likely to be prepared. West Virginia already settled for $161.5 million with drug companies because of opioid-related suits. From that settlement, manufacturer Teva will provide $27 million worth of Narcan.

In the Pacific Northwest, AGC of Washington says that contractors rely on drug-free workplace policies and testing to lower jobsite overdoses. Mandi Kime, its director of safety, says less than 10% of member contractors keep Narcan on jobsites but more would likely include it with better understanding of their liability as Narcan providers. There is also “a lack of knowledge and industry-accepted best practices for Narcan use by contractors,” she says.

In Washington state, as in all states except Idaho, Kansas and Nebraska, a standing order allows individuals to obtain naloxone at a licensed pharmacy without a prescription. “Most people [in Washington] don’t know this,” says Kime, who adds that safety and trade journals are starting to write about Narcan on jobsites.

Kime says members will likely include Narcan on their jobsites if more conversations help them understand their liability as Narcan providers. They have concerns, despite Washington’s Good Samaritan Law, which provides some protection when calling 9-1-1 to try to save a person’s life. There is also “a lack of knowledge and industry-accepted best practices for Narcan use by contractors,” she says.

Workers at a Shawmut jobsite in Los Angeles stretch and practice mindfulness to prevent injuries and avoid the need for pain management.

Photo courtesy Shawmut Design and Construction

Training Day

Placing Narcan on jobsites involves much more than putting it on the site and calling it a day. Its use requires training on how to respond to an overdose, and on wellness programs that include strategies for preventing opioid addiction.

Building Futures Rhode Island, a Providence-based industry partnership that assists apprentices with employment opportunities, has developed apprenticeship training focused on prevention, which includes how to use Narcan.

Its seminars through the Occupational and Environmental Health Center of Rhode Island also feature public health experts presenting on topics including opioid addiction, Narcan placement on sites and resources for recovering addicts, says center Administrator Mary Ellen DiMaio. It also has developed a series of talks on opioids and substance use for mini-trainings, and resource cards that provide information on recognizing and responding to an overdose and how to administer Narcan.

Open shop and union contractors are also collaborating with safety and health associations and medical professionals to assist with addiction prevention programs.

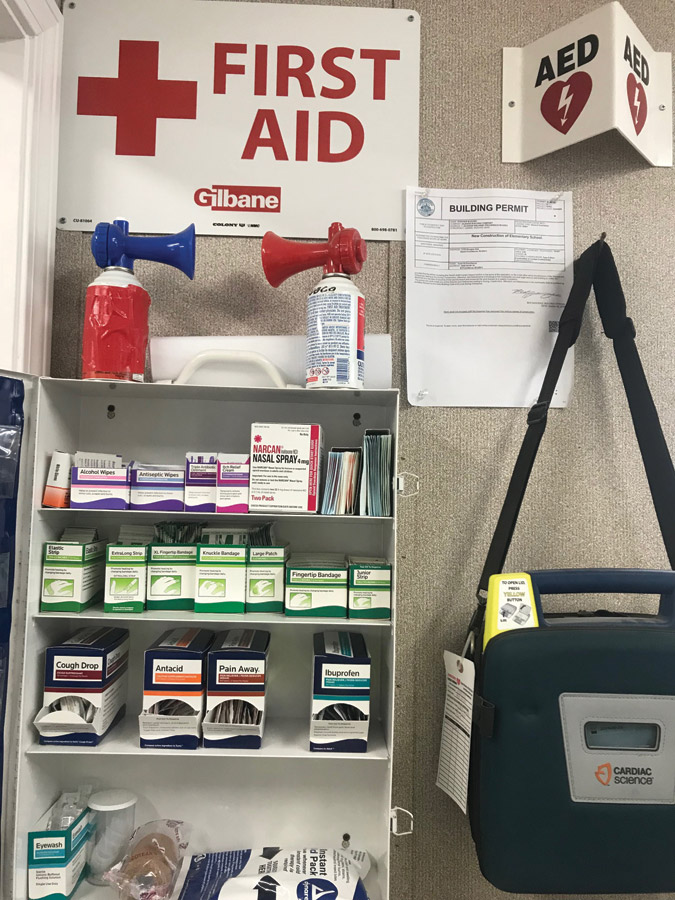

Gilbane Building Co., like Dimeo, is supplying Narcan through Rhode Island’s disaster medical assistance team and its naloxone and overdose prevention education program. The team provides supervised medical direction, based on an agreement with the state medical reserve corps. State officials train workers in how to issue Narcan and “recognize signs of a potential overdose,” says Steve Duvel, senior vice president of Gilbane’s New England division. The program also provides guidelines for medication treatment and storage.

Gilbane, which equips all its active project sites in Rhode Island with Narcan kits, earned state recognition based on standards set by Rhode Island’s Recovery Friendly Workplace Initiative. The only builder in the state to receive such a designation, it’s also rolling out Narcan on Massachusetts and Connecticut projects.

Workers at Boston’s 2019 opioid standdown observe a 150-second moment of silence in memory of the 150 construction workers per 100,000 workers who die due to opioids.

Photo by Emett Smith, courtesy of the Building Trades Employers’ Association

Watershed Moment

On May 3, 2019, dozens of workers in Boston observed a 150-second moment of silence as part of a stand down in memory of the 150 construction workers per 100,000 workers who die due to opioids. “Construction workers should be leading the way in fighting back on stigma to let people know it’s okay to go for treatment,” Martin J. Walsh, then city mayor and now U.S. Secretary of Labor, said at the stand down. “It should start right here on this construction site and in the city of Boston, and we should lead the way for the rest of the country,” said the former Local 223 member who served as its president from 2011 until he was elected mayor in 2013. Walsh also has been open about his own battle with alcohol addiction.

The stand down marked the close of Boston’s first Building Trades Employers Association Northeast Building Trades for Recovery Week. It also convinced contractors such as John Moriarty and Turner Construction to supply Narcan on their Boston area sites. Lee Kennedy Co., which was one of many sponsors of Recovery Week along with BTEA Northeast, also was inspired to place Narcan on its jobs. The Quincy, Mass.-based firm hired a third-party medical provider to conduct brief trainings for all project managers, superintendents, forepersons and safety managers. “One of the largest benefits was an immediate and long-lasting change in the stigma associated with addiction and treatment,” says Jason Edic, Lee Kennedy’s vice president of risk management.

Following the event, BTEA Northeast trained many business managers and stewards in laborers’ union locals in Narcan administration. Through this initiative, the group also collaborated with Boston building trades, Ironworkers Local 7, the North Atlantic States Regional Council of Carpenters, the International Union of Painters and Allied Trades District Council 35 and the Laborers International Union of North America (LIUNA). Laborers’ Local 223—Walsh’s old organization—was the first local to train all jobsite stewards to use Narcan in the Boston area. “Marty was a huge help in getting other trades on board,” says Thomas S. Gunning, BTEA Northeast executive director.

While Boston’s first Recovery Week provided tools and resources—including seminars, training and speaking programs—for more than 25 unions, contractors, and other organizations, “Narcan training was by far the number one attended educational seminar we put on,” says Gunning, adding that as a result, the effort reversed nine overdoses on jobsites using Narcan during the last eight months of 2019. “Nine lives were saved right there,” he says.

But getting to that point was a struggle—both professionally and personally—for Gunning, who says he survived two heroin overdoses in March 2016 thanks to Narcan.

Hooked on Percocet after surgery for a torn labrum discovered when he was being recruited by his college baseball team, Gunning hid his addiction from family and friends for more than a decade until his father, former BTEA Northeast executive director Thomas J. Gunning, fired him. After a long struggle, the younger Gunning found help and returned to work at Lee Kennedy as a union laborer. Not long after returning to work for his father in 2018, the younger Gunning resolved to make Narcan implementation a joint labor-management initiative.

Around the same time Gunning organized the first stand downs, BTEA Northeast and other New England unions, including Ironworkers Local 7, were approached by Narcan evangelist Dave Argus.

Director of operations at Karas & Karas Glass Co. in Boston, he was named a 2021 ENR Top 25 Newsmaker for providing recovering addicts with support. “Now Narcan is at every job we go to,” says Argus, who credits “our sober community.”

Argus, Gunning and Shawn Nehiley, business manager of Ironworkers Local 7 and current president of the union’s New England district council, say they set out to alleviate contractor concerns about potential liabilities and the “taboo” of Narcan on jobsites by raising awareness that it is common and likely that “there are people on drugs on their jobsites.”

Originally planning to equip individual labor union stewards with Narcan to introduce it to jobsites, they quickly discovered recovering addicts often carried their own supply to work. The managers formalized this practice by designating certain workers on site as Narcan carriers. When contractors learned Narcan was already saving lives on their jobsites, their concerns dissipated. “We negotiated with the general contractors so elevator operators have Narcan in the elevator first-aid kit because they already knew how to use it and could get to all the floors quicker than anyone else,” Argus says.

Kyle Zimmer, director of health and safety and the member assistance program for Operating Engineers Union Local 478 in Meriden, Conn., believes “Narcan should be right along with the AED on the jobsite.”

Organizations such as Rhode Island Building Futures conduct training sessions to teach industry workers how to safely administer Narcan to someone suffering from an overdose.

Photos above and below, by Kevin Ferias courtesy Rhode Island Building Futures

Real Risks of Use

In the five years that FDA-approved Narcan nasal spray has been on the market, generally there have been few reported side effects. But recent preliminary findings indicate that when Narcan is not issued quickly enough, or when a person has been issued it more than once, it can lead to damage, especially in those who have suffered prior brain injuries.

As Narcan use increases, a certain percentage of people who overdose and are saved by its use now have a category of brain damage called chemical brain injury, says Frank Sparadeo, a neuropsychologist who specializes in the neuroscience of opioid use disorder—and their numbers are increasing. “It was unclear until about two years ago whether there was any central nervous system damage in these overdose cases,” he says. “Then people started popping up in neurologists’ offices complaining of memory impairment to find out they overdosed and were saved by someone injecting Narcan,” says Sparadeo.

When saving them took too long, they had a period of hypoxia (lack of oxygen to the brain) that resulted in significant memory impairments and even permanent brain injury, he says. “The question is what to do with these survivors, many who are young, who may not be able to return to work. They’re not the same person anymore,” Sparadeo adds. For those who overdose on fentanyl versus other opioids, the probability of brain injury or cognitive impairment is higher. A “sizeable number” of people survive an overdose after receiving Narcan, but no one has estimated the number, he says.

While Narcan use is rising nationwide, it remains a last resort for saving lives in the event of an opioid overdose. This reality has led many organizations to couple Narcan use with a preventative approach to fighting addiction through use of non-medication alternatives to opioids. The laborers’ New England Health and Safety Fund is offering alternative pain relief methods including acupuncture, chiropractic and massage, says Noell Woolley, fund medical program director.

Thomas S. Gunning speaks at BTEA Northeast’s Building Trades Recovery Week.

Photo courtesy of BTEA Northeast

Recognizing that “surgery is a leading gateway for new persistent opioid use,” Goldfinch Health CEO Brand Newland says it has been developing programs that provide opioid-sparing techniques, including multimodal pain relief to enhance recovery after surgery. It has a health surgery concierge program underway with painters’ union District Council No. 30 in Chicago and is launching another with the ironworkers’ New England Council. The Massachusetts Laborers’ Health and Welfare Fund is providing Hinge Health’s digital musculoskeletal clinic, a digital pain management program for chronic back and joint pain, Woolley says. Members with musculoskeletal pain participate in virtual physical therapy and care plans, including guided exercises using an app that provides live feedback from wearable sensors.

The National Association of Homebuilders is offering 30-minute free online physical therapy assessments for individuals with qualifying health insurers before they follow “a pathway that might lead to an opioid,” says Jeff Horwitz, chief operating officer of nonprofit SafeProject US. In 2021, it started distributing free at-home disposal pouches to prevent medication misuse. Horwitz recommends construction companies “work with insurers to require a co-prescription of naloxone for everyone who has received a certain amount of opioid and co-dispense a disposal pouch to get rid of any leftover opioid.”

Genetic testing can also determine addiction risk.

In October, SOLVD Health launched a genetic risk assessment to help physicians decide when to consider oral prescription opioids for acute pain relief. Construction companies are also realizing the need for mental health counseling to prevent substance abuse. Marianne Karg, vice president of Mobile Medical Corp., which provides on-site occupational medical services, including Narcan on construction sites, says onsite proactive behavioral health counseling is increasingly seen as a “must have,” a fact that makes those “in the substance abuse prevention community excited.”

Jamie Becker, director of the Laborers’ Health & Safety Fund of North America health promotion division in Washington, D.C., says the building trades’ opioid task force has been focusing more on mental health and substance use disorder, “which needs to be part of a comprehensive health and safety plan.”

She adds: “It’s been a long time coming, but it seems the rubber is meeting the road in the last couple of years.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment