The U.S. Supreme Court has limited the ability of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to regulate power plant greenhouse gas emissions, and though the court’s opinion referred to a fairly narrow provision within the Clean Air Act, the ruling potentially places broad restrictions on the ability of federal agencies to enact regulations to address the climate crisis, according to several sources.

The key question in West Virginia v. EPA—a decision released on June 30, the final day of the court’s term—was whether EPA exceeded its authority in re-interpreting statutory language within the federal Clean Air Act, specifically Section 111(d), to set emission-reduction goals beyond individual power plants to entire systems in its 2015 Clean Power Plan. In rereading that provision of the statute, the Obama administration’s EPA said it had authority to help facilitate the U.S. energy transition from coal-fired power to cleaner natural gas and renewables.

In its 6-3 decision, the nation’s top court ruled that EPA overstepped its authority.

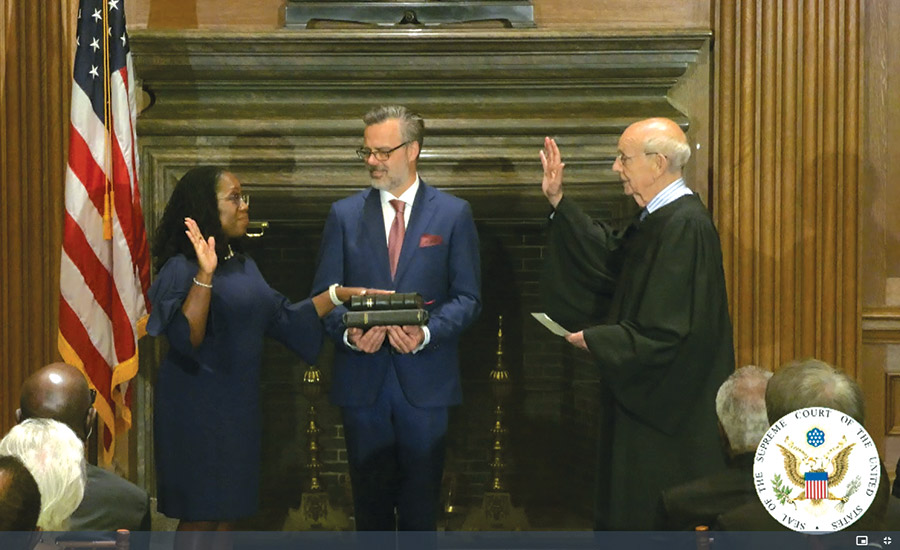

Also on June 30, Justice Stephen Breyer formally stepped down a little after noon, as he had announced he would, after serving for 27 years on the court. He swore in the court’s newest justice, Ketanji Brown-Jackson, who had clerked for Breyer earlier in her career and is widely expected to be one of the more liberal justices on the bench.

Michael Haggarty, associate managing director of Moody’s Investors Service, said in a statement that the June 30 decision will have “little impact on the credit quality or carbon transition-related capital expenditure plans of U.S. regulated utilities, which are being driven more by customer and investor preferences, the declining cost of renewable energy and individual state energy policies.” But he said it will likely “reduce the risk of an accelerated carbon transition timeline driven by federal policy that could adversely affect utility credit, as it is unlikely the U.S. Congress will act as quickly or deliberately as EPA would have.”

Environmental groups say they fear that time is running out to address the climate crisis, and that an accelerated timeline is exactly what is needed.

The Opinion

Writing for the court, Chief Justice John Roberts said: “Capping carbon dioxide emissions at a level that will force a nationwide transition away from the use of coal to generate electricity may be a [sensible solution]. But it is not plausible that Congress gave EPA the authority to adopt on its own such a regulatory scheme in Section 111(d). A decision of such magnitude and consequence rests with Congress itself, or an agency acting pursuant to a clear delegation from [it].”

Roberts cited the major questions doctrine, which applies when an agency asserts rules or powers that are highly consequential and are likely beyond the scope of what Congress intended. “This is a major questions case,” he wrote. For four decades, EPA has traditionally viewed Section 111(d) in relation to individual stationary sources, not entire systems, Roberts said. EPA’s re-interpretation asserts that “Congress implicitly tasked [the agency] and it alone, with balancing the many vital considerations of national policy.... There is little reason to think Congress assigned such decisions to the agency,” he wrote.

In their dissent, Justice Elena Kagan, joined by Justices Breyer and Sonia Sotomayor, wrote: “Today, the Court strips the Environmental Protection Agency of the power Congress gave it to respond to ‘the most pressing environmental challenge of our time,’” as stated in the landmark case Massachusetts v. EPA, which gave EPA authority to regulate greenhouse gasses.

EPA “is committed

to using the full scope of [its] authorities ... to reduce the pollution that is driving climate change.”

— EPA Administrator Michael Regan

Not only does the West Virginia v. EPA decision curb the agency’s authority to regulate carbon dioxide from power plants, it also reduces the options that states and municipalities—and the engineers and contractors that work for them—use to combat them. According to the opinion, Congress will need to pass laws specifically authorizing the creation of a cap-and-trade system or other new programs to limit emissions. “It is one thing for Congress to authorize regulated sources to use trading to comply with a preset cap, or a cap that must be based on some scientific, objective criterion, such as the National Ambient Air Quality Standards. It is quite another to simply authorize EPA to set the cap itself wherever the Agency sees fit,” Roberts wrote.

Brian Turmail, executive vice president of public affairs for the Associated General Contractors of America, said in an email that AGC is reviewing the ruling to gauge how it might impact members. “The challenge is that the ruling does not appear to prohibit EPA from taking future actions, it just identified administrative problems with how [the agency has] been going about it so far,” he said. “Considering that EPA is still crafting a regulation to set limits on greenhouse gas emissions from power plants, the real question is what impact the ruling will have on the agency’s pending rule.”

Jeff Holmstead, a former chief of EPA’s office of air and radiation and now a partner at Bracewell, says that he expects the ruling to have little practical impact on EPA, which is already working on a new rule, had no plans to resurrect the never-enacted Clean Power Plan and was not planning to rely on Section 111(d). “I don’t think this changes [EPA’s] plans very much,” he told ENR.

Limits on Ability to Regulate Emissions

The decision did not raise the specter of Chevron U.S.A. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, a 1984 Supreme Court decision that gave federal agencies broad discretion by courts to interpret the meaning and congressional intent of laws relating to their scope of responsibilities. Environmental advocates had feared that a reversal of Chevron could have severely curtailed agencies’ ability to promulgate any regulations.

But several sources said that although the court didn’t refer to the Chevron case, it ignored precedent that has been applied for more than 30 years. Maya van Rossum, an environmental activist and founder of Green Amendments for All, a policy-oriented nonprofit, notes, “They didn’t explicitly overrule it, but if they are going to ignore Chevron deference, then they might as well overrule it…. If they are not going to apply the precedent, what value is the precedent?”

Bracewell’s Holmstead concurs. The major questions doctrine has been an established part of case law for years. “But they really sort of embraced that doctrine and spelled it out in a way that I think is very significant for the future of the regulatory state,” he says.

As a result, recent efforts by agencies such as the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to enact carbon-reduction regulations may not hold up to legal challenges, he said.

Another potential casualty could be the U.S. Transportation Dept.’s new proposal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the transportation sector, announced June 8. Nick Goldstein, vice president of regulatory affairs and legal issues for the American Road & Transportation Builders Association, says, “The DOT is not staying within its lane. It’s going into an area traditionally reserved for EPA. So, we don’t think there’s the authority for the DOT to do this.”

What’s Next?

EPA’s planned new regulation will provide more protections than the Trump rule, but the agency hopes it will still be legally defensible. The Chesapeake Bay Foundation notes that while the decision narrows the federal government’s authority under the federal Clean Air law, “it leaves room for EPA to act on its duty to tackle carbon emissions from power plants.”

In a statement, EPA Administrator Michael Regan said that while he is “deeply disappointed” in the ruling, the agency is “committed to using the full scope of [its] authorities to protect communities and reduce the pollution that is driving climate change. We will move forward to provide certainty and transparency for the energy sector, which will support industry’s ongoing efforts to grow our clean energy economy.”

Looking ahead to the new Supreme Court term beginning in October, proponents of wider protections for the environment and a range of social issues are worried. The court will hear another blockbuster case, Sackett v. EPA, on the first day of the new session. The justices will consider the extent to which the Clean Water Act protects ephemeral and intermittent streams that do not have a direct surface connection to navigable bodies of water. The West Virginia v. EPA ruling, and the court’s decided tilt to the right “is a harbinger of things to come…. It does not bode well” for environmental cases, von Rossum says.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment