The days may finally be numbered now for the rusting, nearly three-quarters-of-a-mile-long Massachusetts Turnpike viaduct that looms over the Charles River, cutting through the city’s Allston neighborhood at Boston’s western gateway.

State transportation officials recently announced they will pursue plans to tear down the 1960s viaduct as part of a massive $1.7 billion highway reconfiguration and redevelopment project.

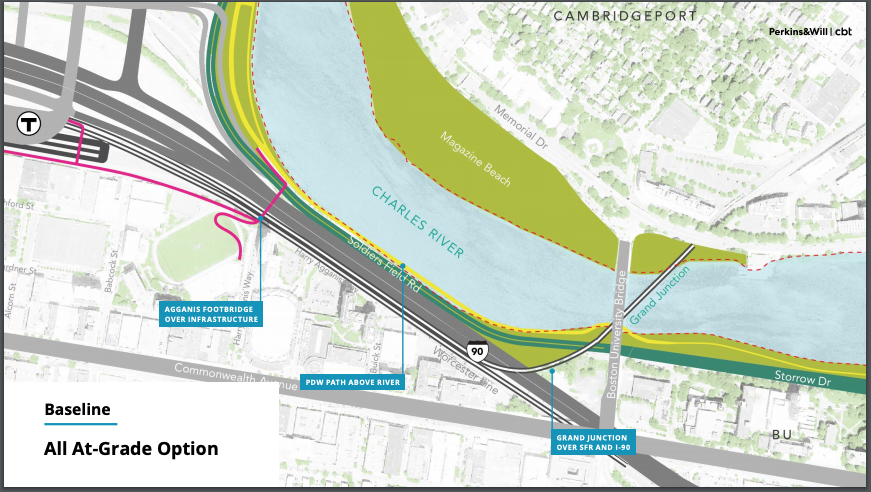

The viaduct will be replaced by an at-grade and straightened span of highway and rail tracks, with the reconfiguration helping to free up more than 100 acres of land owned by Harvard University, for redevelopment.

The decision by the Massachusetts Dept. of Transportation comes after years of push and pull over the fate of the project, with then Secretary Stephanie Pollack last fall pushing off a verdict on whether to simply rebuild the current viaduct or go with the far-more ambitious at-grade plan.

But Pollack’s wavering triggered strong pushback, with business, political and civic leaders praising MassDOT’s decision to scrap the viaduct plan and go with the at-grade option.

Supporters of the at-grade option have argued it will reconnect the Boston’s Allston neighborhood with the waterfront along the Charles, with the viaduct and the elevated stretch of Turnpike having acted for decades as a giant barrier cutting off access.

“This is such a renaissance and such a significant city building opportunity,” Rick Dimino, president of a business-backed nonprofit, A Better City, and a vocal supporter of the at-grade option.

Members of the state’s Congressional delegation, such as Sen Ed Markey and Rep. Ayanna Pressley, now former Mayor Marty Walsh, and dozens of state lawmakers ranging from Boston to Central Mass had weighed in during the regulatory process with comments supporting the at-grade option.

“We applaud MassDOT for its design decision at this critical stage, and … look forward to fighting for this important project to receive the federal funding it needs moving forward,” Markey and Pressley said in a statement.

While support for the current iteration of the Allston I-90 Multi-Modal Project has surged, so has its total price-tag, rising by $400 million from $1.3 billion last year.

The price includes an array of infrastructure work, from highway and bridge construction to new streets, parks, walkways, and a $180 million commuter rail station. There will also be a pedestrian/bicycle bridge connecting Agganis Way to the walkway and bike path planned for pilings over the Charles River.

State officials began looking at options for dealing with the aging viaduct more than a decade, but find a solution was complicated by the complex logistics involved with reconfiguring the site.

A particular challenge has been a narrow section of the site called “the throat” where planners have struggled to figure out how to squeeze in, all at-grade, the Turnpike, Soldiers’ Field road, and rail tracks.

Boston University, which abuts the site, helped break the logjam, agreeing to provide a seven-foot stretch of land. In addition, a planned pedestrian and bike path will now be built on pilings over the river, while the shoulders of the highway have been narrowed as well.

The decision to move forward with the ambitious project will also put it on the radar for a potential federal infusion of funds should the $1 trillion, bipartisan infrastructure project pass, Dimino contends.

In order to make that happen, however, state transportation officials and other stakeholders have roughly two years of permitting work ahead in order to win approval form various state and federal regulatory agencies, Dimino said.

While the project is not shovel ready yet, supporters will make the argument to federal officials in charge of the infrastructure purse strings that it is a “shovel worthy” project, Dimino said.

In outlining its infrastructure goals, the Biden administration earlier this year began using the term “shovel worthy” term to signal support for more complex projects that have not yet crossed the permitting finish line.

In fact, the massive highway reconfiguration and redevelopment project could compete for money under two different funding streams built into the $1 trillion package, he said.

However, the timeline is not open-ended, suggests a report by A Better City, with the federal government likely to put a “premium” on projects that can break ground in the next two or three years before 2024 and the next presidential election.

“You don’t want this parage to march by and not be part of it,” Dimino said. “That would be so sad.”