Aluminum composite panels cladding London’s Grenfell Tower were the main reason for the 23-story residential block becoming totally enveloped in flames in under three hours after a refrigerator caught fire on the fourth floor, concludes a UK government inquiry.

The disaster killed 72 people in the early hours of June 14, 2017, at the recently refurbished building in the Kensington and Chelsea area of west London.

“The design of the refurbishment, the choice of materials and the manner of construction allowed an ordinary kitchen fire to escape into the cladding with disastrous consequences,” notes Martin Moore-Bick, a retired Court of Appeal judge who is chairing a two-phase inquiry into the fire.

Any blame and potential prosecutions will follow a second, 18-month phase of the inquiry that is scheduled to begin in 2020.

The first phase, completed and publicly released in October, probes how the fire started and spread and also the performance of emergency services.

Any blame and potential prosecutions will follow a second, 18-month phase of the inquiry that is scheduled to begin in 2020. Officials will concentrate on the decision-making behind the building’s refurbishment as well as the responses of local and central government bodies.

What to do about other buildings remains a concern at the highest levels of government. Since the fire, work to remediate faulty buildings has been patchy.

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson told members of parliament that “progress is not as fast I should like,” particularly in the private sector where “too many building owners have not acted responsibly.”

Of the 168 potentially still at-risk private sector apartment buildings, 24 are being re-clad while no work or planning has started for the rest, according to the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. To accelerate progress, this May the government pledged $260 million (£200M) for private sector remediation work, accusing some owners of being “reckless.”

By this October, Grenfell-type rainscreen, or moisture barrier, had been removed from 114 privately owned high-rise residential buildings in England leaving 321 still likely to fail building regulations. In the government housing sector, 97 buildings still need remediation. (In England, privately owned buildings are described as publicly owned and government-run housing is described as part of the social sector.)

|

Related Article |

Meanwhile, the inquiry report has provided a clearer narrative of the Grenfell Tower tragedy's origins.

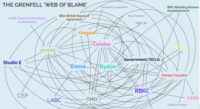

Completed in 1974, the concrete- framed building is owned by Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and was then managed by an external tenant management organization. To upgrade the block, in June 2014 the management organization awarded a design/build contract to Rydon Maintenance Ltd., which subcontracted the cladding to Harley Facades Ltd. The project architect was Studio E.

With the work done, the council signed a certificate of completion in July 2016. Since Moore-Bick found the work failed to comply with relevant building regulations, the work's certification will be questioned in inquiry’s next phase.

The cladding system generally comprised Aluminium Composite Panels supplied by Arconic Architectural Products SAS, a French subsidiary of Pennsylvania-based Arconic Inc. These “Reynobond PE” rainscreen, or moisture barrier panels were made up two 0.5-mm-thick aluminum sheets sandwiching a 3-mm polyethylene core.

For insulation generally, a layer of Celotex RS5000 polyisocyanurate polymer foam was fitted behind the rainscreen, with a roughly 15-cm gap for ventilation and drainage.

Moore-Bick concludes that the fire was sparked by a refrigerator in a fourth floor apartment. As fire took hold, newly fitted uPVC window frames deformed in the heat allowing flames into the external cladding. The speed at which the fire spread was “profoundly shocking,” he notes.

First spotted slightly after 1 a.m., flames escaping the kitchen window were seen to ignite cladding within four minutes. Less than 20 minutes after flames appeared, 19 floors of cladding were alight. A minute later, flames were at roof level, igniting a decorative “crown,” which spread fire horizontally around the tower.

Burning Drips of Polyethylene

The aluminum composite panels were the “principal reason” the blaze spread rapidly, concludes Moore-Bick. The polyethylene cores melted and fueled the growing fire, boosted by the foam insulation boards. Burning drips of polyethylene from the crown cladding and elsewhere were “the principal mechanism for horizontal and downwards flame spread,” he notes.

Arconic has already spent nearly $40 million on legal and advisory fees as it faces potentially huge claims from Grenfell survivors and relatives of the dead.

This past June, lawyers representing 247 plaintiffs filed a wrongful-death lawsuit in Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas against Arconic, Celotex and the refrigerator manufacturer.

In a statement at the time, Arconic said: “While we provided general parameters for potential usage universally, we sold our products with the expectation that they would be used in compliance with the various and different local building codes and regulations.”

Regulations in the U.K., Europe and the U.S. allow such products “including in high-rise buildings,” added the company. “Nevertheless, in light of this tragedy, we have taken the decision to no longer provide this product in any high-rise.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment