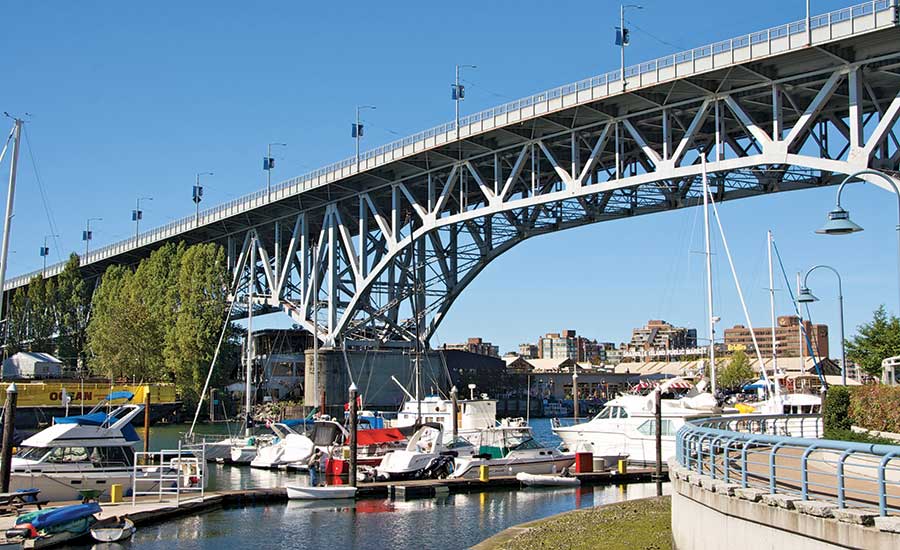

Vancouver, British Columbia could be a hotbed of construction soon, with the inking of a record $5.4 billion transit expansion over the next decade and $2.1 billion in new infrastructure investment on everything from affordable housing and new sewer lines to a seismic upgrade of the 64-year-old Granville Street Bridge.

Developers are wary of the latter, however, because of new fees they face that could limit project scopes.

The Mayors’ Council on Regional Transportation, which represents Vancouver-area municipalities, and TransLink, the regional transit authority, will oversee the new transportation spending, which includes a new light rail line, an extension of Vancouver’s SkyTrain network, and expanded bus service.

The federal government is pumping more than $1.5 billion into the effort, with British Columbia adding $1.9 billion. TransLink will shoulder the largest share, roughly $2 billion, through fare increases, parking taxes, property taxes and fees on residential developers.

“This milestone could not have been possible without all levels of government working together to finalize a funding plan,” said TransLink CEO Kevin Desmond, in a statement.

The plan includes 900,000 hours of additional bus service on 75 different routes. There are also plans for six new stations on the SkyTrain’s Millennium line, with a 40% increase in service on the route and on the Expo line. The transit money will also pay for 203 new SkyTrain cars on both lines, construction of a new Surrey-Newton-Guilford light rail line and $57 million in road improvements.

The Trudeau government is in the third year of $143-billion-plus, 12-year infrastructure plan that has been dominated in part by federal efforts to reach agreements with provincial and local governments on how to spend the dollars and how various governments will contribute.

“People in the Lower Mainland have been stuck in gridlock for far too long,” said Selina Robinson, Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing, in a statement. “With the region expected to grow by one million more residents in the next 30 years, there is a desperate need for action.”

Meanwhile, Vancouver's infrastructure plan faces pushback over concerns that high fees on developers could kill projects and slow construction activity.

City builders are on the hook to foot more than half the bill for improvements through “development contributions.” The city council approved the plan in July.

Vancouver’s development community only agreed to the charges in exchange for a pledge by city officials to hire more planners to speed up new project approvals, says Anne McMullin, CEO of the Urban Development Institute, which represents area developers. Project review times over the past few years have doubled, “as well as carrying costs,” she says. “These costs get passed to the buyer.” Developers, through various fees, covered 33% of the previous capital improvement plan, compared to 55% for the current one. The earlier plan also was less than half the cost, at about $830 million.

Rising fees could, in turn, prompt some developers to rethink or even cancel projects, McMullin contends.

A Vancouver developer recently canceled plans for a 12-story condo high-rise that would have featured 200 market-rate units and 30 units of supportive housing for the mentally impaired, she notes. In pulling the plug on the project, the developer in part blamed rising city fees. In response, city officials said they have offered $12 million in grants to help pay for the project’s affordable housing element.

Roughly half of Vancouver’s capital improvement plan, slated for the 2019-2022 timeframe, will pay for renovations and upgrades to city infrastructure. Half of the city’s water and sewer system is more than 50 years old, while 40% of city-owned buildings are at least 40 years old, say city officials.

The plan also calls for building up to 1,600 new units of affordable housing and adding 1,000 new daycare slots, as well as a library expansion, a public plaza, an outdoor pool and support for a subway expansion.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment