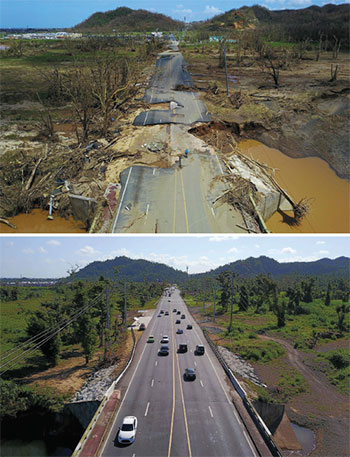

Billions of dollars have been spent to help Florida, Texas and Puerto Rico recover from the devastating and record-breaking 2017 storm season. Tons of debris have been removed, houses have been razed, roads have been repaired, bridges have been rebuilt, and power has been restored to 99% of Puerto Rico.

Yet the regions affected by Harvey, Irma and Maria are still fragile—and the forecast calls for 10 to 16 named storms this year. Low-grade tropical-force winds could decimate Puerto Rico’s power grid; homes in Houston could flood in a rainstorm; and Florida is still reliant on an overburdened transportation system to move people out of the state if there’s another statewide evacuation.

The mantra to “build back better,” is used in Puerto Rico to describe the government’s plan to make the island more resilient to future storms. But in a rush to return to normalcy, most people just want to build back.

Funding shortages, lack of political will and federal policies are all obstacles to rebuilding to be more resilient to the next round of storms. Perversely, most government financial incentives are rigged in favor of rebuilding instead of resilience, including the Stafford Act, which largely requires money be used to replace exactly what was there before a storm. Additionally, disaster spending is accounted for as an emergency appropriation, as a war is. “From a budget math perspective, it’s like free money,” says Josh Sawislak, AECOM’s global director of resilience and a former associate director of climate preparedness and resilience in the Obama administration.

“Are we implementing what we know, and do we have the fortitude and guts to get this done?”

– Illya Azaroff, AIA

The sheer magnitude of the 2017 storm season, with its estimated $306 billion in damages, is beginning to push the issue. Federal and local governments are reexamining how they are rebuilding after a storm. Federal Emergency Management Agency Administrator Brock Long has repeatedly said he wants to make the agency more proactive.“We are really sending a strong message that we want to not only build back, but build back better,” says Jonathan Hoyes, director of FEMA’s Office of Federal Disaster Coordination. The House has passed legislation that would loosen some restrictions on federal recovery money, and, for the first time ever, the federal Dept. of Housing and Urban Development has set aside $16 billion in Community Development Block Grants for hazard mitigation.

At the same time, however, President Trump in August 2017 rolled back an Obama-era order that required federal agencies to build infrastructure to higher standards or not at all on flood plains.

“We know what we need to do,” says Illya Azaroff, co-chair of the American Institute of Architects risk and reconstruction committee. He points to the National Institute of Building Sciences study that shows every federal dollar spent on hazard mitigation saves an average of $6. “But we have more conversations than we do have action. Are we implementing what we know, and do we have the fortitude and guts to get this done?”

Some people, like Ricardo Álvarez-Díaz, past president of Puerto Rico’s Builders Association, say becoming more resilient will require systemic changes in culture, policy and funding. “It’s a Band-Aid mentality,” he says. “We have to start thinking holistically.”

Paul Horgan, head of commercial insurance for Zurich North America, agrees in a recent white paper: “Unfortunately, in the aftermath of a disaster, there is rarely the time to think beyond recovery. … In reality, we should be taking the time—in advance—to make sure the lights will stay on when the next disaster strikes.” Incentives available today, he continues, need to be strengthened “so we do not continue to build back to the same standards that failed.”

The struggle to build back better is illustrated best in Puerto Rico. Hurricane Maria’s 155-mph winds swept through the entire island, causing more than $100 billion in damages and resulting in the direct and indirect deaths of up to 4,645 people, according to a recent Harvard University study. More than 300,000 homes were damaged, and Gov. Ricardo Rossello has requested $95 billion to rebuild the island. The territory, despite repeated brushes with hurricanes, had not addressed resilient building or infrastructure, and because of budget shortfalls, had not even maintained what infrastructure it had.

“In a way we are kind of in the same place we were before the hurricane,” says Álvarez-Díaz. “And that’s not necessarily a good thing.”

In addition to the immediate recovery money from FEMA, $1.5 billion in CDBG funds is expected to reach the island later this year. Most of that money will go toward housing. Puerto Rico is in line to receive an additional $18.44 billion in CDBG money, including more than $8.3 billion for hazard mitigation and resilient rebuilding, but it could be more than a year before that money starts to reach the island. The slow pace of federal funding is a big problem for bankrupt Puerto Rico, which, unlike Florida or Texas, has little money of its own to start the rebuilding process.

The failure of Puerto Rico’s electric grid and its rebuilding have been at the forefront of the territory’s efforts. The system was poorly maintained when Hurricane Maria hit, leaving the entire island without power for weeks. As of June 5, at least 9,600 people are still without electricity.

After the storm, FEMA gave the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers the task of rebuilding the entire grid. More than $2 billion in federal funds have been spent just to get the lights back on. Limited by a federal law that requires emergency disaster funds be used to rebuild what existed before the storm, the Corps essentially rebuilt the old grid. On May 18, FEMA ended the Corps’ power restoration mission and the work of restoring the last 20,000 customers went to the territory’s utility. A recent report by the Associated Press says that in some cases, the distribution system may be worse than it was before, with at least one instance of a line being attached to a living tree.

“God forbid another hurricane in Puerto Rico this year because we are not yet resilient,” says Stephen Spears, president of the Puerto Rico chapter of Associated General Contractors. “All of our infrastructure, water, power and telecom is still fragile.”

In an acknowledgement of the grid’s fragile state, the federal government allowed the Corps to extended its temporary power contract with Louis Berger to maintain more than 500 generators at key locations at least through August.

“In a way we are kind of in the same place we were before the hurricane. And that’s not necessarily a good thing.”

– Ricardo Álvarez-Díaz, Architect

The Puerto Rico government in December announced plans to spend $17.6 billion to rebuild the grid yet again, this time more resiliently with microgrids, more renewable power and a more efficient grid that is being designed by the U.S. Energy Dept. The 10-year plan includes $5.3 billion for overhead and underground distribution lines, $4.9 billion for overhead and underground transmission lines, $1.7 billion for substation upgrades, $3.1 billion for generation and $1.5 billion for distributed energy.

Contract awards have followed. Mammoth Energy Services subsidiary Cobra Acquisition signed a $900-million contract with the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA) on May 29 to finish restoration work and begin reconstructing the grid. On June 4, MasTec announced a $500-million agreement with PREPA for restoration work and reconstruction work that MasTec says will begin in the third quarter of this year.

Related Articles:

Still-Recovering, Texas Coastal Towns Aim For Resilience

TxDOT Replaces Harvey Damaged Span Over San Jacinto River

‘Informal’ Building

It may be more complicated and take longer to fix the island’s other problems, including “informal” building, improper design, lack of compliance with code and lack of maintenance. At least 55% of the island’s buildings are constructed without plans or permits, in flood zones, on unstable hills, or even on land that doesn’t belong to those living in the home.

Similar issues exist with the island’s infrastructure. Projects were not designed correctly, aren’t in compliance with code and aren’t maintained, says Emilio Colon, past president of the World Council of Civil Engineers and former executive director of the territory’s water utility.

“The government doesn’t want to make things harder—or to force people to comply,” says Colon. “It’s a massive effort; no one wants to do it. It becomes a vicious circle.”

More than 300,000 homes were damaged by Maria and will cost $31 billion to rebuild, according to Rossello. A program through FEMA and the territory’s housing department is working with seven contractors to get people living, at least temporarily, back in their homes. But the next step, to move those people into homes that are in safer locations and built to code, will likely prove challenging.

Puerto Rico has announced it will implement construction methods that emphasize sustainability, quality, durability and mold resistance, and it will increase the use of LEED and the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS) Fortified Home standards. The island, working with FEMA, has also embarked on an effort to update its building code to meet the 2018 International Building Code by the end of the year. The island adopted the 2009 IBC code in 2011. The problem, though, isn’t the code, it’s compliance, several people say.

Álvarez-Díaz says only 5% of the housing stock is up to the 2009 code. That 5% weathered the storm fine, according to anecdotal evidence. “In one of our projects that we designed and was under construction, there was no damage. Not even one broken window because it was up to code,” he says.

“We could very well get another hurricane this season, maybe two— and I think we will be back to square one.”

– Emilio Colon, WCCE

Umberto Donato, who is working on the code committee, says forcing the 2018 code to be adopted may cost too much. “We’re completely aligned with the need to build safe and sustainable structures that will withstand the weather that we have in Puerto Rico, but that has to be balanced with economic reality of the island,” says Donato, president of DDD, a Puerto Rico construction company.

Azaroff points out that building codes are reactive and provide only a minimum for building safety. The industry needs, instead, to be proactive and incentivize more resilient structures.

Colon says while government has made steps in the right direction, a more comprehensive, cohesive plan is needed to make sure the right things happen. “Until everyone gets together and starts complying, it’s all going to be very difficult. We could very well get another hurricane this season, maybe two—and I think we will be back to square one. It’s not the way it should be.”

A Gold Standard

By sharp contrast, Florida has been becoming more resilient to hurricanes since 1992, when Hurricane Andrew hit South Florida.

Many of the state’s residents have reached a “pain threshold,” in which they are willing to discuss and make hard and expensive choices. “It’s on their mind because of repetitive occurrences. It’s front of mind,” says Jason Bird, Florida resilience practice leader at Jacobs.

The state’s preparedness is reflected in a No. 1 ranking from the IBHS for its residential building-code system among 18 hurricane-prone states.

A triage team led by University of Florida investigators catalogued just 1,100 structures that sustained damage from wind, water intrusion and storm surge from Hurricane Irma. Irma fell short of being a design-level wind event, with loads ranging from 25% to 97% of design levels, according to the team’s report.

Florida created a statewide building code after Category 5 Hurricane Andrew caused more than $23 billion in damage, destroying more than 63,000 homes and damaging more than 101,000 others.

Despite the success of the code, there has been pushback from the state’s building industry. Last year, before Irma landed, the Florida legislature voted to end the state’s automatic adoption of the triennial International Code Commission updates. Using the existing state code as a foundation, the Florida Building Commission will periodically consider model code changes recommended by the ICC.

“There’s no silver bullet. It’s about understanding critical parts of the system and managing the overall system.”

– Jason Bird, Jacobs

The codes, however, don’t address all components at risk in a storm. “There’s no silver bullet,” says Bird. “It’s about understanding critical parts of the system and managing the overall system to maintain reliability given the potential risk.”

In South Florida, that means building seawalls to manage storm surge and sea-level rise; in Jacksonville, that means hardening the wastewater system; and in the Panhandle, it means using nature-based solutions like mangroves to reduce the impact of wave energy, Bird says.

Irma left more than 36% of Florida’s electric customers in the dark. In a May workshop, all utilities reported having made efforts to harden transmission and distribution networks in recent years. Florida Power & Light, the state’s largest electricity provider, noted in a presentation that while hardened systems don’t prevent outages, they do provide for faster restoration. The utility’s customers were without power for an average of 2.1 days.

Similar proactive measures gleaned from past storms benefitted Florida’s transportation network, with the state department of transportation reporting no major effects from the storm. The storm did highlight the state’s weak evacuation system. With the entire state under a mandatory evacuation order, all arteries out of the peninsula were clogged, forcing thousands to shelter in place during Irma.

An October 2017 FDOT study identified measures to improve evacuation, such as extending emergency shoulder use corridors, constructing additional lanes at the I-75/Florida’s Turnpike interchange, and filling gaps in camera and dynamic message board networks.

Flooding also remains a concern. Anath Prasad, former state transportation secretary and president-designate of the Florida Transportation Builders’ Association, notes that some sections of I-75 and major parallel routes in the state’s north barely stayed above water.

Given the increasing pervasiveness of storm-related flooding in Florida and elsewhere, Prasad wonders if it’s time for state DOTs to discuss “whether 100-year storm is the norm to design around.”

Repetitive Losses

Despite repeated flooding—Houston has had three 500-year floods in the last three years, including Harvey—Texas is just now coming to terms on what it means to rebuild to be more resilient. Harvey’s record rainfall of up to 60 in. caused $125 billion in damages, according to the National Hurricane Center. More than 300,000 structures were flooded throughout southeast Texas, at least 160,000 of those in Galveston and Harris counties alone.

Unlike Florida, which has a strong statewide building code, Texas has no statewide building code, and IBHS ranked the state fifteenth out of 18 hurricane-prone states.

A big part of the problem is that Texas is split on what the problem is. According to Ali Mostafavi, a civil engineering professor at Texas A&M, informal and formal studies show that half of the decision-makers and engineers believe Harvey was a “1-in-1,000” storm, while the other half believe that “Harvey is our new norm.”

Mostafavi, who is part of an American Society of Civil Engineers effort to identify resilience practices implemented after Harvey to help inform future planning, says no matter whether Harvey will occur again in our lifetime, the cost of making resilience investments, “could save a lot of lives. We recognize the tremendous impact not having resilient infrastructure will have on communities.”

Not everyone sees it that way. In April, the city council passed modifications to the Chapter 19 floodplain ordinance, requiring new structures built in Houston’s 100- and 500-year floodplains to be elevated to 2 ft above the 500-year flood elevation. “You would have thought that they were trying to steal property,” says Jim Blackburn, co-director of the Severe Storm Prediction, Education and Evacuation from Disaster Center at Rice University in Houston and a professor of civil and environmental engineering. “We have not adopted the fundamental understanding that we are going to need going forward. People don’t belong in some of these areas. But to some, including our engineering community, it’s like an abdication. It’s admitting defeat. But we can’t engineer our way out of this—not with the money we have.”

Had all of Houston’s homes been built to 2 ft above the 500-year flood elevation, 84% of the homes flooded during Hurricane Harvey would have been spared, according to the city’s public works department.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is in the process of updating its precipitation frequency estimates. That update could change the definition of what a 100-year flood and 500-year flood is for Houston and affect the cost benefit analysis for both existing projects and future resilience projects across Houston.

Regulatory floodplain fixes will only address part of the problem—40% of the structures that flooded were outside the flood plain. In the next few months, the city will modify building codes for those structures. “That’s an indication of probably we should strengthen some of our development codes and also the fact that we have challenges in terms of our urban infrastructure,” says Stephen Costello, Houston’s chief resilience officer.

For now, the area’s flood resilience is equivalent to what it was before Harvey hit as the area awaits federal funding for projects that will take five to 10 years to complete.

Texas is awaiting $5 billion from the Housing and Urban Development Community Development Block Grant program approved last fall, and another $10 billion, including $4 billion specifically for hazard mitigation, has been allocated through a second round of CDBG funding announced earlier this year.

“It kind of comes down to how resilient do you want us to be and how much are you willing to pay for that level of resiliency?” Alan Black, director of the Engineering Division at Harris County Flood Control District (HCFCD), told members of the American Society of Civil Engineers at a May 18 panel discussion on recovery and resilience.

“You can harden every pump station with a generator, but that has to be balanced with the funding they have.”

– Jill Hudkins, Tetratech

Such a balancing act is similar for all areas affected by disasters. “The clients we work for have to balance many things—short-term needs vs. long-term needs, and they need to need to continue living,” says Jill Hudkins, a water infrastructure expert at TetraTech, which worked with at least 150 different communities during the 2017 hurricane season and is still working with about 50. “You need to balance economics. You can harden every pump station with a generator, but that has to be balanced with the funding they have.”

Houston and surrounding Harris County is focused on priority repairs. Almost all of the city’s 22 main bayous have been cleared of storm debris, but HCFCD is still working on clearing the final channels, Buffalo Bayou and Cypress Creek. The district has an initial list of $84 million in priority repairs across Harris County’s bayous, creeks and other infrastructure, encompassing roughly 500 repair projects. Construction is expected to begin later this year, with completion in 2019.

HCFCD and Houston have identified 12 long-term projects on which they would work together. The $700-million scope of work would include individual home buyouts, elevations and demolitions/rebuilds, additional flood gates and the conversion of a landfill into a flood detention basin.

Separately, HCFCD is formulating its own set of proposed resilience projects, which would be funded by a $2.5-billion bond program that’s scheduled to be voted on in an Aug. 25 special election—a date that coincides with Hurricane Harvey’s one-year anniversary.

The package would fund more than 150 projects over 10 to 15 years in Harris County, says Matt Zeve, director of operations for the district.

Discussions of a third reservoir to join the existing 70-year-old Addicks and Barker reservoirs have yet to come to fruition. In the meantime, the Corps is continuing to upgrade Addicks and Barker. The $73.8-million dam safety modification project at both reservoirs, which began in August 2015 and will end in June 2020, will replace the outlet structures of both reservoir dams and improve the seepage control, says Edmond Russo, deputy district engineer for the Corps’ Galveston District.

The Corps plans to begin a feasibility study to determine improvements at both reservoirs. It will also begin a feasibility study of the Metropolitan Houston Regional Watershed, to look at hydrologic conditions across Houston’s 22 watersheds and examine what programs may help provide for flood risk reduction and resiliency.

Private Solutions

Sawislak is convinced that private corporations, insurance companies and rating agencies will push the pendulum toward pre-disaster spending over post-disaster rebuilding, like-for-like.

“The market is starting to price this risk, and that is going to drive behavior better than any regulation,” he says.

If there’s any silver lining to the 2017 storm season, it’s that it brought the conversation of resilience to a new level.

“Mother nature is a fabulous advertisement for resilience,” says Bird. “As storm events happen, it’s very much an eye-opener to the importance of making sure that we are planning, building and designing infrastructure to be more resilient.”

By Pam Radtke Russell, Louise Poirier and Jim Parsons

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment