Technology, transitions and transformation are all topping the discussions among transportation professionals. The industry awaits the actions of a new presidential administration and the impending impacts of connected and automated vehicles and other disruptive trends regarding infrastructure while taking stock of the U.S. Dept. of Transportation’s 50th anniversary, celebrated last October.

While the DOT has attained some significant accomplishments, such as in aviation safety statistics, it still has much to do in terms of passenger rail safety, said Ken Mead, a former inspector general to the U.S. DOT. Speaking on a panel at the Transportation Research Board’s annual meeting this month in Washington, D.C., he noted the area’s Metro woes. He asked, “Does the Federal Transit Administration have the capacity to pull off oversight”of transit safety issues?

He also brought up the ongoing debate in Congress regarding whether the Federal Aviation Administration should cede to private management the modernization of air-traffic-control infrastructure. As for highways and bridges, “we have to look through a different lens. The DOT is turning into a check-writing function.”

In general, “it’s time to redefine the DOT’s mission in 2017 terms,” he said.

Jack Schenendorf, who served on the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee staff for 25 years, obliquely alluded to the current political climate by noting the loss of a bipartisan spirit in Congress when it came to transportation legislation. “The system has become far more political,” he said. Politicians wanting to talk to their counterparts on the other side of the aisle about transportation “now feel constrained to give their views.”

He emphasized the long-standing issue of not raising the federal gas tax to pace with inflation, as well as the red tape that delays projects and programs. The current negative results of underinvestment in infrastructure—bottlenecks, aging bridges and roads, and deaths—“are nothing compared to what’s coming,” Schenendorf said. “If we don’t figure out what the DOT is going to look like for the next 50 years, then things are going to be a lot more bleak.”

Automated Future

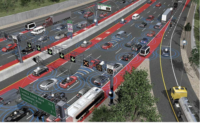

Carl Andersen, FHWA’s connected-vehicle program manager, said that, despite reports of crashes involving AV test vehicles, including a fatal incident in Florida earlier this year, “no single incident will derail efforts to launch new technology that is lifesaving.” It may be as long as 50 years before AV-specific design features become evident in the nation’s highways, Andersen added. “Roads will look like they do now for a long time,” he said.

Still, it was clear from the range of AV- related sessions at TRB that transportation engineers and administrators want to be prepared for the transition, whenever it occurs.

In a session on the implications for infrastructure design, construction, maintenance and management, panelists identified a range of impacts, from roadway geometrics and pavement performance to work-zone deployment.

Of particular concern is AVs’ ability to handle unique existing roadway features in urban and rural settings. Zachary Doerzaph, director of the Center for Advanced Automotive Research at the Virginia Tech Transportation Institute, said engineers need to be prepared to respond to faster turnovers in technology.

Brian Ray, a senior principal engineer with Kittelson & Associates, noted that transportation agencies may need to adjust their maintenance priorities, placing greater emphasis on pavement markings and signage to preserve AVs’ mobility and safety advantages.

But while AVs may inspire both wonder and worry, especially when considering the cost associated with accommodating them, Ray said transportation professionals should recall when automobiles were introduced to an infrastructure system that had evolved around horse-drawn vehicles.

“We’ve been here before,” Ray said.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment