As the Superfund program approaches its 30th anniversary, it is at a crossroads. To finish cleaning up nearly 1,300 designated hazardous waste sites—some dangerous to human health—sources say the program needs funding. But with a difficult economy and little congressional support for reinstating a dedicated trust fund, those resources could be hard to come by. The result is a slowing of the already lethargic pace of site completions.

Meanwhile, some industry firms have developed solutions of their own to accelerate site cleanups.

In December 1980, after the contamination at Love Canal in New York and other toxic-waste sites made national headlines, Congress passed the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compen-sation and Liability Act. Since then, the Superfund program has overseen cleanups at more than 1,080 sites on the Environmental Protection Agency’s National Priorities List (NPL).

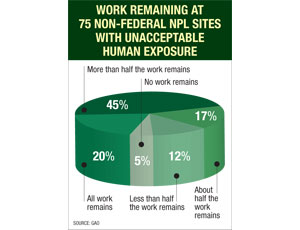

Now, in 2010, approximately 1,270 sites remain, 75 of which EPA says pose a health risk through “unacceptable human exposure.” While there was a surge of site completions in the 1990s, the number of sites completed in recent years has slowed to a trickle.

According to the Government Accountability Office, there are not enough resources to complete construction at the existing and future sites on the NPL. In a report released on June 22, GAO concludes, “EPA’s future costs to conduct remedial construction at non-federal NPL sites will likely exceed recent funding levels.” GAO estimates EPA’s costs for remediation will range from $335 million to $681 million over the next four years, compared with the $220 million to $260 million annually allocated from fiscal years 2000 to 2009.

That shortage of funds has led to slowdowns in site completions. At a June 22 hearing before the Senate’s subcommittee on the Superfund program, toxics and environmental health, John Stephenson, GAO’s director of natural resources and the environment, said, “We found that limited funding for the Superfund program has caused delays in cleaning up the Superfund sites.”

At the same hearing, Mathy Stanislaus, EPA’s top official in the agency’s office of solid waste and emergency response, said part of the reason completions have slowed is because “cleanup work we are doing today overall is more difficult, more technically demanding and consumes considerable resources at fewer sites than in the past.”

Still, funding remains an issue. Stanislaus said that, in fiscal 2008, EPA was unable to move forward on 10 of 26 new construction projects that were ready for funding “due to the resource needs of ongoing construction work.”

Stanislaus called for more appropriations from Congress and reinstating the Superfund “polluter pays” tax, an excise tax on oil and chemical manu-facturers to cover costs to clean up “orphan” sites—those locations where a “potential responsible party” cannot be identified.

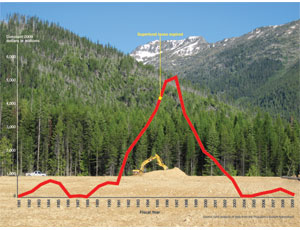

The original Superfund tax, created near the inception of the Superfund program, expired in 1995. The fund itself ran out of money in 2000. Since then, cleanups at orphan sites have been financed primarily by annual appropriations from the general fund, usually in the range of $1.2 billion to $1.3 billion a year.

Support for reinstating the Superfund tax seems to be gaining on Capitol Hill. Sen. Frank Lautenberg (D-N.J.) introduced legislation to bring back the tax, and Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.) has introduced a comparable bill in the House. But Ed Hopkins, the Sierra Club’s director of environmental quality programs, says prospects for passage of the measure this year are slim. “There’s a limited amount of legislative time left in the year,” he says. Neither chamber has yet held a committee or subcommittee hearing on the bills. However, he adds, “I believe that some groundwork has been laid … that could help legislation pass hopefully next year.”

Construction industry sources say reinstating the Superfund tax, along with increasing appropriations, would help accelerate site completions. Mike Elia, president of Sevenson Environmental Services Inc., Niagara Falls, N.Y., says, “Since the Superfund tax expired, the program has slowed down, and most of the effort has been directed at the megaprojects or the projects that expose the public to the greatest health hazards.”

Sevenson is working on several large sites in the Northeast and completed work at projects at more than 119 sites on Superfund’s NPL list, including the Sag Harbor, N.Y., site (see cover). Some firms report a mild increase in activity since 2009, when the President signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act into law. ARRA provided an additional $600 million for ongoing and new construction projects. EPA says a total of 57 construction projects received funding, 26 of which were new construction projects. “These projects would not have been able to start without the ARRA funding,” said EPA in response to written questions from ENR.

Black & Veatch, Overland Park, Kan., an EPA Superfund contractor throughout the history of the program, currently is working on three sites that have received stimulus funding. “Over the past several years we’ve seen a definite pickup in the market,...

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment