The owners of 19 California coastal powerplants—including two nuclear facilities—may have to spend billions to install closed-loop cooling towers to protect marine life. The state Water Quality Control Board passed regulations on May 4 that require plants using once-through ocean-water intakes for cooling to reduce water use by more than 90%.

The rule, finalized by the board after five years of study and hours of debate, cites estimated annual mortality rates of 2.6 million fish and 19 billion fish larvae from up to 15 billion gal of water drawn daily to cool the plants. It “requires that the location, design, construction and capacity of cooling-water intake structures reflect the best technology available for minimizing adverse environmental impact,” says a board spokeswoman. She says detailed cost estimates won’t be known until plant owners submit them six months after the mandate passed internal legal review.

Compliance would cost one plant, the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station in San Diego, $3 billion, even if the necessary leases and approvals were available to install a closed-loop cooling tower, says David Kay, manager of environmental projects for the plant’s majority owner, Southern California Edison Co., Rosemead. San Onofre operates two combustion-engineering pressurized-water reactors with a combined generating capacity of 2,300 MW. Kay says that even with permits in place, space limitations make adding a cooling tower impossible. “It is not technologically feasible to retrofit to 93% less intake,” he says.

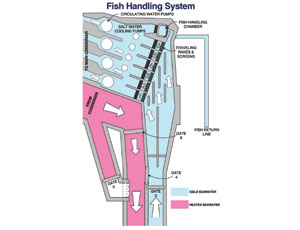

Edison already has spent about $150 million, by order of the California Coastal Commission, to mitigate damage to marine life. San Onofre’s once-through systems suck in fish and eggs with as much as 1.6 billion gallons per day of ocean water, discharging warm water back into the ocean. Mitigation included a replacement kelp bed and restoration of 150 acres of tidal wetlands. The plant also includes a fish protection system that uses a velocity-cap opening on the intake valve, creating a horizontal flow so fish can better detect pressure change and swim away.

For those fish that do make it into the intake pool, a series of concrete veins creates a current that directs fish to a corner where a stainless-steel elevator basket lifts them into a stream to the ocean. Kay estimates 95% of adult fish that get trapped in the intake are returned to the ocean safely, but fish eggs and larvae don’t usually survive the trip.

Edison and San Francisco-based Pacific Gas and Electric, owner of the 2,150-MW Diablo Canyon plant in Avila Beach, have until 2025 to develop a solution that is acceptable to regional water officials. The two four-loop pressurized-water nuclear reactors of Diablo Canyon in San Luis Obispo County are seen as important because they do not create greenhouse gases and are reliable when other alternative-energy sources are offline.

For the state’s 17 other power generating plants using once-through intakes for cooling, the regulations will be phased in. Within a year, owners will have to install large organism-exclusion devices or screens with gaps of no more than nine inches. Compliance dates range from 2015 for El Segundo, Harbor and Morro Bay powerplants to 2020 for the Haynes, Huntington Beach, Redondo, Alamitos, Mandalay and Ormond Beach stations.

At the same time, operators will be working to determine “best technology possible” to meet federal Clean Water Act marine-life protection requirements.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment