Cement scientist Brent Constantz wants concrete to be the "hero" that cleans up dirty coal. "The reality is, coal is not going away," he says. "We need to meet the world’s power demands without emitting more carbon." His answer? A new type of concrete that sequesters carbon without disturbing its traditional binder: portland cement.

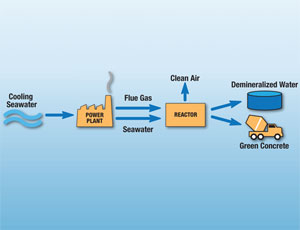

This past summer, the Stanford University professor’s Los Gatos, Calif.-based startup, Calera Corp., began making cement from flue gas and seawater at Dynegy’s gas-fired 1,500-MW Moss Landing Energy Facility. At first, Constantz hoped to replace portland cement, which emits about one ton of carbon dioxide per ton produced. But after some industry pushback and more research, he now says he can use Calera aggregate synthetic stone, sand and gravel to capture CO2 and still produce net gains.

Constantz cemented the new course in Las Vegas on Feb. 3 appropriately, on the first day of this year’s World of Concrete show speaking to 100 world-leading scientists and engineers during a 90-minute seminar. In the packed room, Constantz, who owns more than 70 patents for medical cement, assured the group that Calera could be used to replace portland though it is not essential. "The way to get it accepted is probably through the aggregate," he says.

The pitch worked. Florian Barth, a structural engineer and incoming president of American Concrete Institute, says Calera "has great potential." The seminar "was promising," adds Steven Kosmatka, vice president of Skokie, Ill.-based Portland Cement Association. "Although their process needs further refinement…we must keep a careful watch on Calera," says another scientist who attended.

Unlike cement, aggregate is more voluminous in concrete, making up at least 75% of the mix. "If we just replace the sand, we get to carbon-neutral," Constantz says. The new route helps calm fears over using a new, synthetic binder. Kosmatka calls the new approach a "home run." Barth adds that it could solve other industry problems. "It is increasingly difficult to get mining permits," he notes.

Calera has gone from 10 employees last year to 100 today and is working on a pilot plant on the East Coast. By 2010, it plans to have a factory cranking out its calcium and magnesium carbonate.

Until now, technologies being developed for polluters center on underground carbon capture and sequestration. CCS could offset 70 years of emissions, perhaps hundreds more, according to the World Coal Institute. But Calera potentially has no shelf life as long as the world builds with concrete, trapping up to a half-ton of CO2 in one ton of material, Constantz says. At full scale, Moss Landing alone could trap 3.4-million tons per year; that’s like putting over a million hybrids on the road, he adds.

As promising as it is, though, engineers want to see more data. "They have a long way to go," Kosmatka says. "This is not something that people are going to be ordering next month."