Canada's National Energy Board granted approval in December to the proposed Mackenzie Gas Project, which would string a natural gas pipeline from the upper-reaches of the Northwest Territories, Canada, 745 miles south into Northern Alberta. Before the $16.2-billion project can proceed, backers must put in place a funding framework.

"Mackenzie needs to compete on a supply-cost basis with other sources of supply," says Pius Rolheiser, Calgary-based Mackenzie project spokesperson." It remains the critical challenge today to be cost- competitive with shale gas, liquefied natural gas and potential Alaska projects."

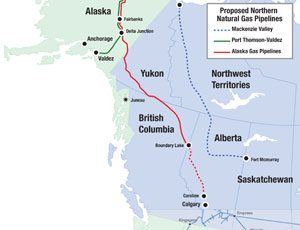

While Mackenzie runs primarily south, staying entirely in Canada, two proposed pipelines connecting natural gas fields in Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, to Alberta via Canada's Yukon Territory and British Columbia both find themselves in negotiations with suppliers and plan Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) applications in one to two years.

It may take much longer before gas is flowing south from northern Alaska, however. The U.S. Energy Information Administration released a report late in December saying that there won't be need for a new major natural gas pipeline in Alaska for the next 20 years, especially considering the high costs associated with construction.

The earliest proponents see a decision on the Mackenzie project, which would develop three major Canadian Arctic natural-gas fields, is 2013. The earliest gas would flow would be 2018. That's the best-case scenario, as the 30-inch-dia pipeline and associated infrastructure require approval for about 6,000 regulatory construction permits.

Randy Ollenberger, analyst for Montreal-based BMO Capital Markets, says his company doesn't believe the Mackenzie project is needed in the next 10 years "given the abundant unconventional gas opportunities that are more economic." As shale-gas production continues to increase, Mackenzie will likely requires government subsidies to go forward, he says.

He wants to see a shared "risk and reward" agreement with the Canadian government. The companies involved� Imperial Oil (the team lead), Shell Canada, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil and the Aboriginal Pipeline Group�take a " long view" of the project and anticipate the markets will need the gas by 2020 and 2030. "A decision to construct would be based not so much on current market conditions and near-term forecasts," Rolhseiser says. The company believes demand will grow further and declines in conventional production positions Mackenzie well. Re-staffing the project team requires funding.

If the pipeline is constructed and placed in operation, it could handle 1.2 billion cubic feet of gas per day, about two-thirds of that coming from the anchor fields, opening up room for other shipping agreements.

TransCanada and ExxonMobil joined on the Alaska Pipeline Project, which actually has two proposed routes to carry 1.1 billion cubic feet of gas per day. One route, ranging from $32 to $41 billion, runs a pipeline about 1,700 miles (734 miles in the U.S. and 966 in Canada) from Alaska's North Slope to Alberta' s existing pipeline infrastructure. The second option, ranging from $20 billion to $26 billion, would transport the gas in an 800-mile pipeline with " multiple" potential shippers and expect to make public the chosen option when announcing future agreements, says James Millar, TransCanada spokesperson. The companies plan to file with FERC in 2012.

The proposed Denali Alaska Gas Pipeline, owned by BP and ConocoPhillips, would put 4.5 billion cubic feet per day of gas through a 1,750-mile pipeline (730 miles in the U.S. and 1,020 Canadian) along a nearly identical route as the first TransCanada option at a cost of $35 billion. After closing a solicitation period this year for companies to commit to transporting gas, Denali plans application filings with FERC in 2011.

"Denali has received bids for significant capacity from potential shippers," says Bud Fackrell, Denali president. "We will carefully evaluate these bids and their conditions and continue confidential negotiations with potential shippers in an effort to reach binding agreements."

Along with the companies, the First Nations tribes of the Northwest Territories want the Mackenzie project�the largest capital project ever for the region�to happen, says Fred Carmichael, chairman of the Aboriginal Pipeline Group. "For the Mackenzie Valley and Beaufort Delta regions, this project is the only realistic way to create an economic future and an independent and self-sufficient future for northern people."

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment