M.A. Mortenson Co Mort Mortenson and his 1987 Volvo are both icons at the Minneapolis firm

|

M.A. “Mort” Mortenson Jr. says his favorite project in 48 years at the family construction firm was dismantling 300-plus Minuteman missile sites in South Dakota. But it’s probably a good thing the firm could not win more demolition jobs: Building things up has worked out much better for the 72-year-old entrepreneur and his Minneapolis-based M.A. Mortenson Co., which he has led for almost four decades as chairman.

One of construction’s most technically savvy and prolific design-builders, Mortenson faces the future—even an economically uncertain one—with global sales at a record $2.2 billion and backlog up 13% in 2007 to more than $4.2 billion. To its credit, the firm has amassed a stable of innovative structures, out-of-the-box construction approaches and a fiercely loyal workforce.

|

Mortenson has long stuck to a motto of “quiet competence,” but the firm, its managers and projects are now making more industry noise. The firm has long embraced design-build and has led the industry in the use of 3D and 4D building information modeling (BIM). Taking that path allowed it to even consider executing the wildly geometric designs of Frank Gehry and Daniel Libeskind that others passed up, let alone finishing such landmark projects with limited hiccups.

Traditionally not big industry schmoozers, Mort Jr., his blood relatives and “family” of longtime executives and staff still command strong industry respect. “They don’t see value in pounding their own chest, but they are one of the giants in the last few years,” says Donald S. Evans, vice chairman and chief marketing officer of CH2M Hill Cos., Denver, and a past chairman of the Design-Build Institute of America. But Mort Jr. says that even as M.A. Mortenson Co. expanded its geographic and market reach under his watch, Mort Sr. would still wonder if his son “knew what he was doing.”

M.A. Mortenson Co |

M.A. Mortenson Co

|

M.A. Mortenson Co

|

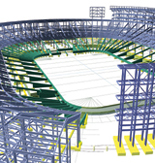

| 4D modeling (center) is key to taking $288-million Minneapolis stadium from rendering to reality | ||

Mort Jr., who bought out the hard- money building contractor founded by his father in 1954, hardly fits central casting’s idea of a well-heeled, aggressive construction contractor. The soft-spoken entrepreneur quotes Robert Louis Stevenson poetry to motivate his 2,750 salaried and craft workers and relishes his role as the company’s cheerleader-in-chief. “I love construction. It’s a tremendous business, not just for me but for every person who participates in building a project,” he says. Adds oldest son David, 45, a senior vice president and heir apparent in the longterm succession plan: “There is no one who exemplifies servant leadership better than my father does.”

Mort Jr.’s 1987 Volvo, with close to 215,000 miles on it, is an icon parked each day at 7 a.m. in front of the firm’s non-descript headquarters outside the city. “Mort just believes he’s the owner of the business, but that his life shouldn’t be different,” says Thomas F. Gunkel, a 26-year veteran who earlier this year became the first non-family member to add CEO to his president’s title.

| “Employees want to be empowered and invested in.” — THOMAS F. GUNKEL,

PRESIDENT AND CEOs |

But even as he slowly implements the long-planned succession, Mort Jr. remains an engaged competitor pushing his firm to pioneer new markets such as wind-energy development in the U.S. and larger projects, although always with an eye on managing growth and the bottom line. Unlike his own father who did not start the company until he was 48, Mort Jr. grew up in the firm, dutifully earning an engineering degree but honing his corporate skills as a self-described “business-book junkie.” The firm, solely owned by the Mortenson family, does not disclose its earnings, but Mort Jr. says it has never suffered a loss.

Mortenson grew larger on a steady diet of public and private-sector work, building up the skyline in Minneapolis and elsewhere across the U.S., even pursuing hydroelectric, wastewater-treatment and other infrastructure work. But the pitfalls of competitive bidding troubled Mort Jr., and by the mid-1990s, he wanted new approaches before the firm “was hauled down by an industry not making substantial progress to change.”

The result was Mortenson’s 1994 Center for Construction Innovation, a think tank of three key executives pulled from their regular jobs to spend a year with industry experts and deep thinkers to position the firm for a better future.

The result was Mortenson’s decision to “choose customers rather than projects and pursue markets where we would learn,” says think-tank participant John Wood, now senior vice president in charge of the firm’s highest-profile projects and its local work. The emphasis on design-build, integrated project delivery and adoption of manufacturing-type modeling technologies followed. D-B is now 40% of the business and virtually exclusive to its growing energy and federal construction segments, says Gunkel.

Armed with new tools and internal excitement, Mortenson decided to take on Gehry’s awesome design for the $275-million Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, which had already undergone years of contracting upheavals “The project was so different that we would be forced to do things differently,” says David, noting that two key subcontractors dropped out because of execution fears. Among extensive use of BIM to find trouble spots in the design and schedule, Mortenson was able to convince Gehry to allow ceiling panels to be fabricated offsite using computerized tools rather than painstakingly installed, “Michaelangelo-style,” he adds. “Gehry absolutely agreed.”

Guy Lawrence / ENR Disney Concert Hall was daunting to build but a landmark in use of high-tech tools.

|

That signature job was followed several years later by a $70-million addition to the Denver Art Museum, another angular epic that challenged the project team but showed Mortenson’s ability to use tools and leadership to get to the finish line. “Never in my 28 years in the business have I seen anyone that good in managing the group,” says Curtis Mayes, director of preconstruction and engineering for LPR Construction, the project’s Denver-based steel-erection sub. “Mortenson stepped up, took control of the files and did interference checking. By the time we got into construction, we had zero conflicts. It was a huge springboard for us.” LPR and Mortenson have worked together on 30 projects, he adds.

Despite the push for collaboration, the two jobs were not without later legal and performance glitches. On the Disney project, Mortenson had to file suit under California law to settle design-related claims. The suit was dismissed after a 2006 settlement with the firm and 10 subs, says Gunkel. The experience in litigiousness is why Mortenson has not set up an an office in the state, officials say.

New problems with the Denver facility, allegedly stemming from design issues, is also re-involving Mortenson. Gunkel confirms the firm has executed a $2-million temporary roof fix because of leaks from last winter’s heavy snowfall. It is now working with city officials to devise what will likely be a costlier permanent solution.

But Mortenson insists that despite such bumps, the project experience was invaluable. “They were transformational for our company,” says Gunkel, also a...

Related Link:

Related Link:

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment