...water-related public-works project. “Then, they accepted this project. It was delayed. And the message was, ‘Let’s just get through this. Let’s get it to the end line.’ ” And it was the end of the line in more ways than one.

Another part of the study notes that contractors often are undercapitalized, leverage their working capital and cycle that capital through the business dozens of times in a year. Jeffrey M. Levy, chief executive of specialty contractor Railworks Corp., New York City, says that the margin for error in business today is slimmer because cash is managed even more tightly. “Cash used to be a lot looser, and that allowed you to balance cash needs,” says Levy. “Today, there’s not a lot of float, and that saves owners and takes away profit from contractors. The discipline of cash management is much more advanced than it was 20 years ago. The rules have changed, and it takes away a degree of freedom.”

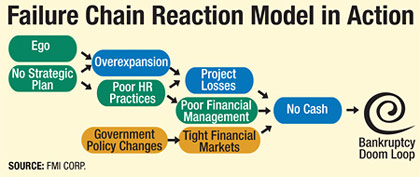

The culture and systems of an organization also play a role in what FMI describes as the “failure chain reaction.” A lack of financial discipline and respect for financial thinking, a lack of a clear process for deciding which projects to take on and a lack of innovation all can set the stage for trouble. FMI also discovered that strategic planning at many construction firms is not strategic. “We have found that a lot of construction companies do strategic planning but don’t have very good strategies,” say the FMI researchers in the report. After getting caught up in the process and completing it, many companies never successfully figure out what kind of firm they are and where they should be going.

|

|

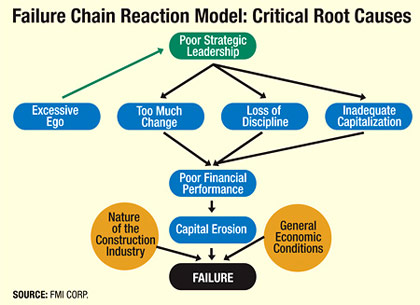

FMI only listed the companies that had had financial trouble, but one or more of the five key factors FMI identified—loss of management discipline, too much change, changing too fast, poor strategic leadership and excessive ego—can be detected in some of the following well-known financial failures.

Morrison Knudsen Agee: symbol of ego and bad diversification.

|

Morrison Knudsen

Ego is associated with one of the industry’s most infamous failures, 1996’s bankruptcy of Morrison Knudsen Corp., which was founded in 1912. With Harry Morrison’s widow a big stockholder, the board hired William Agee as chief executive. He began diversifying into businesses that included transit cars—not exactly the kinds of project MK was known for. “He had a history of being in the public eye,” says one former senior MK executive. “He was quite a self-promoter. He was intelligent, but he had a lust for the limelight….Every month, there was a new butterfly to chase.”

Almost two out of three companies whose executives were interviewed by FMI say excessive ego was involved in their company’s financial crisis. “There are many ways in which an excessive ego can express itself that distort reality, leading to .misperceptions� that put the company at greater risk, says FMI�s report. Says Rice, �I�ve heard it over and over, and it starts in the executive suite. If you make bad decisions, it gets companies into trouble.�

S.J. Groves & Sons

A lack of a plan to produce a successor can put the wrong person in the top job. At S.J. Groves & Sons Co., which quietly sold off its assets and stopped taking on new work around 1989, the successor to the Groves family business was an executive who �had no understanding of the construction industry or the desire to learn it,� Charles A. Murren III, who worked at the company when he was a young graduate engineer, wrote to ENR in an e-mail. The company lost money on some big projects and had to selloff nonconstruction assets such as real estate, expensive artwork, antique furniture, a gold mine and a horse farm. Murren now is head of his own company and models his practices on what he saw while working at Kiewit Corp., Omaha. At his own company, based in Grayson, Ga., Murren pledges to have an employee stock-ownership plan, training and staff development and promotion from within.

Stone & Webster

Besides the dysfunctional decisions that result from excessive executive ego, FMI also points to problems stemming from executives having too little �skin in the game,� or too little to no ownership stake. Too little personal involvement and a lack of business management capabilities led to deadly strategic mistakes at Boston-based Stone & Webster. It was one of the most widely studied underperforming businesses and it eventually took refuge in bankruptcy before being sold to Shaw Group, Baton Rouge, La., in 2000. Through the 1990s, when the company’s core business of nuclear powerplant work was dwindling, Stone & Webster had too few independent, outside directors, and the directors overall owned very little company stock, according to several studies and sources.

Stone & Webster had large cash reserves, “but for all its resources,” the company never adjusted, says Railwork’s Levy, who worked for Stone & Webster early in his career. “I think there was a huge gap in leadership. When you grow up in a business that isn’t there anymore, what do you do?”

Stone & Webster did not make any significant acquisitions or bring in outside managers who could change the company’s culture or direction. Instead, Stone & Webster took on risks associated with infrastructure and overseas power projects, business segments in which the company had never worked. “Stone & Webster had never taken construction risk overseas. We were not a risk contractor, yet they were applying themselves in markets with huge risks,” says Levy.

|  |

Encompass, Modern Continental and J.A. Jones

Too much change can be as deadly as making changes too late. New services, new clients, sudden volume upswings and entry into new territories are well-known sources of risk. Hiring new senior leaders, project managers and even installing a new accounting system “can all be changes that set events in motion toward the failure of the organization,” say the FMI researchers.

Modern Continental’s demise largely is blamed on owner Les Marino’s desire to operate a national company rather than one dependent on work in its hometown of Boston. Marino “was promoting an image of the company that seemed...

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment