|

| Labor rules for big projects would change under proposed union pacts. (Photo by Guy Lawrence for ENR) |

New York City’s construction unions and contractors for years have negotiated labor deals at arm’s length, sometimes punctuated by strikes like the early July walkout by two operating engineers locals that halted big Manhattan projects for a week. Today, they are focused on a common enemy—nonunion developers thriving across the city. The upshot is closer labor-management relations, which this fall may usher in vastly more competitive work rules for some building sectors.

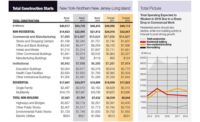

“Unions are waking up to the fact that their real market share is deteriorating around the city,” says Chris Ward, executive director of the General Contractors Association of Greater New York. The changes are in three new project labor agreements (PLAs) that local building trade unions and the Building Trades Employers’ Association negotiated this summer to streamline shift times, holidays, overtime pay and other rules across 40 construction collective-bargaining agreements. The pacts, governing megaprojects above $250 million, market-rate residential and affordable housing, also introduces no-strike, no-lockout clauses.

The deal’s spark is a labor movement wounded by nonunion competitors, says George Reilly, business manager for plumbers’ and gasfitters’ Local 1 in Queens. “We have seasoned labor guys at that negotiating table who realize we need certain changes.”

The threat is diffuse. Dozens of nonunion developers built small projects outside Manhattan over the past decade, and some, such as Brooklyn’s Boymelgreen Developers, graduated to larger ones. “The problem is the residential market going vertical in the outer boroughs,” says Steve McInnis, political director for New York City carpenters’ district council.

As nonunion developers began building in the fertile Manhattan mid-rise market, local unions began to react. The carpenters, plumbers, laborers and reinforcing ironworkers have teamed up with contractors to approach owners with project-specific deals. Three years ago, Local 1 and the Association of Contracting Plumbers created a joint “target committee” that develops work-rule, overtime-rate and staffing-level packages to win contracts. “I think we’ve done 35 of those proposals, and we have won 25 jobs,” says Reilly.

Ward says laborers have reduced pavement gang crews from 12 workers to six to compete with nonunion contractors. McInnis adds that carpenters launched a “market recovery” package in July of lower wages and benefits for outer borough and northern Manhattan residential projects up to 12 stories.

Coupled with these initiatives is the success of a PLA signed in 2004 by the New York City School Construction Authority and the building trade unions for a $4-billion school rehab and renovation program. It calls for only a 5% overtime premium for offpeak work and streamlined work rules and holidays. It created a windfall for union subcontractors, which have won billions of dollars of work that nonunion firms used to win with rock-bottom bids.

Nonunion developers are taking heed. Ken Haron, president of Artimus Construction, a nonunion housing developer in Harlem, recently signed on with metallic lathers’ and reinforcing ironworkers’ Local 46 in Queens because its two-day concrete-pour cycle saves him time. “The union delegates negotiated directly,” he says. “They understood our limitations.”

Related Links:

Related Links:

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment