The business of engineering and construction has always been about riskpioneering methods under dangerous conditions with no guarantee of being paid on time, or at all. This kind of work has bred generations of risktakers whose zeal to complete a tough job and seek out even tougher challenges has propelled the industry forward for centuries. Such bravado, however, has allowed some executives to let egos get ahead of sound business judgement and out of step with the firms interests. The result has been the disappearance of many storied industry names in this unforgiving line of work.

But there also are the exceptions, firms founded in the 19th Century that have faced adversity but also opportunity and still are going strong in the 21st Century. Of companies appearing on ENRs Top 500 Design Firms and Top 400 Contractors lists for 2003, more than 70 originated before 1900 (click here to view list). There probably are hundreds more.

The secret to longevity for these designers and contractors is finding the right mix of hubris and humble pie, creating a culture of adaptable entrepreneurs that can change with the times and preserve the company for future generations without letting greed get out of control. "The only way these firms survive is because of generosity, not being overly greedy," says Hugh D. Rice, managing director of management consultant FMI Corp., Denver. "Its about making sure you protect the golden goose."

|

|

| Rigging contractor carted meat in 1870s (above). Now it lifts more high-profile loads. (below left) (Photos courtesy of George Young Co.) |

Long-lasting firms today have already learned that sobering lesson. "In our business, I think that trying to keep hold of your ego is sometimes a difficult thing," says George S. Young, fourth-generation president of family-owned George Young Co., a Philadelphia mechanical contractor and rigging specialist founded in 1869.

Originally a cartage company for prepackaged meat, the firms roots are tangled up in family lore. Youngs great-grandfather, Charles Young, bet the firm during a poker game. "Great-uncle George won the company and changed the name," Young says. It eventually became Philadelphias premier material handler for construction materials and heavy objects including the Liberty Bell, which it has moved four times in history. "The challenge is trying to remember what your core competencies are and not branch out so far that you lose a grip," says Young. "You have to be able to adapt to the changes in life, technology and the business climate."

|

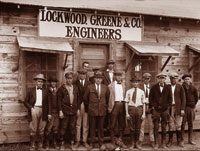

| Employees owned the firm by the 1920s, but it became CH2M Hills 80 years later. (Photo courtesy of Lockwood Greene) |

Adapting has been a watchword for one of the industrys true elders, engineer Lockwood Greene, founded in 1832. The firm, which began designing textile mills in New England, followed that business to the South and added a host of process and high-tech manufacturing industries over time. It was perhaps one of the first in construction to embrace employee ownership. Staff saved the engineering unit after its mill management business "went bust in the Depression," says CEO Fred Brune. Through the 1950s, there were up to 400 employee shareholders, he says.

But they could not rescue the firm decades later when executives sold an 80% share to German contractor Philipp Holzmann whose own financial problems eventually forced Lockwood Greene and another American contractor, J.A. Jones Inc., founded in 1890, into bankruptcy last fall. Jones was sold off in pieces.

Lockwood Greenes biggest adaptation is yet to come, as the Spartanburg, S.C., firm adjust to its new role as a unit of CH2M Hill Cos., Denver, which bought it last October. "We had other suitors with whom we would have been more independent," says Brune. "But we are now viewed as a credible and well-managed part of the enterprise. We are not just a portfolio player."

|

| Wright defined Seattle skyline, including Space Needle. (Photo courtesy of Space Needle Corporation) |

Howard S. Wright Construction Co., Seattle, also has learned some hard lessons on ownership change since its founding in 1885 by its namesake, a former cabinetmaker. It remained family-owned for three generations, during which time it built and rebuilt much of its base city. But the unexpected death of Howard S. Wright III prompted the companys sale to New Zealand-based Fletcher Challenge Ltd. in 1987.

"The company languished under [Fletcher] and didnt grow well," says Brad Nydahl, now CEO. "They started competing on low-bid public projects when the company was used to doing private relationship-based work."

The company quickly got into trouble and by 1996 was back in employees hands. "Right now, there are nine employee owners, but this will jump to 30 in the next six months," says Nydahl. "[It] has provided more of an entrepreneurial environment." He says 20% of Wrights total revenue comes from jobs under $1 million. "We dont want to be the biggest," he says. "We would rather grow slower, building relationships."

|

| Water work pushed Weston & Sampson in 1920s. (Photo courtesy of Weston & Sampson) |

Weston & Sampson Engineers Inc., a Peabody, Mass., firm founded in 1899 by enterprising sanitary engineer Robert Spurr Weston, also is counting on long-held market ties. "People talk of changes in the marketplace all the time," says CEO Michael Hanlon. "But I see our business as grass roots, municipally based." He claims that 90% of its $21 million in 2003 revenue is repeat business. "I refuse to believe that we are a commodity," Hanlon says.

But Hanlon has no plan to follow some peers in "selling out," despite recent offers. "You may gain money, but you lose control. We dont want big brother in another city calling the shots," he says. "Were going to pass this firm on to the next generation."

E-J Electric Installation Co., a New York City electrical contractor founded in 1899, has been passing the torch successfully since estimator Jacques Mann joined in 1912 and later bought the firm. "We are now the oldest independently owned electrical contractor in the U.S.," says his son, J. Robert Mann Jr., now chairman.

|

| E-J Electric lit up New York in 1922. (Photo courtesy of E-J Electric Insulation Co.) |

From the start, E-J focused on providing "specialized" services, including the firms long and innovative association with movie houses and theaters in the first third of the 20th Century. That link helped blunt the effects of the Depression. In World War II, E-J branched into shipbuilding, installing electrical systems in naval vessels. "We were among the first to train and employ women doing electrical work," Mann says.

Periodic building recessions in New York City occasionally threatened. "Back in 1972-73, we were down to a staff of 10," Mann says. "All we could do was hold on and work for the next job." But by 2002, E-J reported revenue of $106.8 million.

For a firm founded in the 19th Century, E-Js approach to the 21st Century is surprisingly straight-forward. "We take a lot of pride in our history and in the high-profile projects we have worked on," says Anthony E. Mann, Roberts son and current president. "That kind of reputation attracts top people." But he jokes that he is already grooming his four children, all under 11, for a future role.

|

| Bechtel has long led the pack, even into Iraq (left). (Photo courtesy of Bechtel) |

Bechtel Group Inc., San Francisco, also is in its fourth generation of family leadership. Riley Bechtel now runs the global construction behemoth that his great-grandfather W.A. Bechtel launched as a road grading business in 1898. "He would not have known about Six Sigma, but he figured out how to do dams and powerplants and believed in continuous improvement," says Riley Bechtel.

|

Bechtel Groups commitment to privacy in its ownership and business dealings has led to speculation in the industry and in the press about financial ups and downs. The company has also long fended off rumors about overly close relationships with government officials. "When your names on the door, you care about the reputation of the place," says Bechtel. "We have a sound record of compliance and a strong book of government work."

Bechtel says that a non-family management core of about 50 executives now owns the largest stake in the contractor. The trend toward increased outside ownership began when he took over from his father, Stephen Bechtel Jr., in 1990. Riley Bechtel does not anticipate ownership pushing farther down into the firm. "I want to get our owners around a table and not have to use a P.A. system," he says.

Next-generation leadership is an issue for Gilbane Building Co., Providence, R.I., which has kept ownership in its extended family since 1873. In January, it announced that Paul Choquette Jr., 65, the sixth consecutive family member to head the building contractor, would relinquish his roles as chairman and CEO to slightly younger cousins. Thomas F. Gilbane Jr. took over as chairman and CEO, while William J. Gilbane Jr. now is president and chief operating officer. Choquette becomes chairman of Gilbane Inc., the holding company.

|

Gilbane stayed close to its roots for years, not leaving Rhode Island for jobs until after World War II and not forming out-of-state offices with some autonomy until years later. "The decision that the fourth generation made to decentralize has been critical to our growth," says Choquette. The firm, whose founder came off an Irish potato ship, had almost $2.8 billion in revenue in 2002, with record earnings that year and in 2003, says Tom Gilbane. "Too many family businesses are satisfied with the status quo," says Choquette.

Gilbanes owners all are family members, but the firms unique culture still keeps non-members from bolting and attracts new ones. "Future leaders of this company need to be stacked up like firewood," says Choquette. Gilbanes board now is dominated by outsiders and its top management team includes 15 non-Gilbanes who have been there 20 years on average, says Tom Gilbane.

|

| Gilbanes (above) still run firm, a Providence, R.I., staple even in 1903. (Photos courtesy of Gilbane Building Co.) |

Even so, the Gilbanes and their work force are concerned about future family leaders. "Our people are anxious about the fifth generation that will come into the company," says Choquette. His own son, Paul Jr., 30, has only been in the firm for three years. "We have to be careful about how ready they are to step up," he admits.

While not family-owned, Chicago-based engineer Sargent & Lundy credits its legacy for the firms longevity, despite the collapse of its former mainstay of nuclear power construction and ups and downs elsewhere in global power markets. With annual revenue of $335 million, the firm has closely followed its original leadership model set in 1891 by company founder Frederick Sargent, who had been one of Thomas Edisons chief mechanical engineers. "We call it a revolving ownership," says Chairman and CEO Paul Wattelet. "We have 27 owners, and they all are promoted from within. When they are age 65, they are required to leave," he says. Owners hold engineering tenures for at least 15 years before they are invited to sit on the board, a limit that pressures them to bring in new business.

"This company didnt know what a salesman was until 1985," Wattelet says. "As a company, we are becoming more and more management focused and the whole form of advancement here is an incentive. Id like to think my proudest achievement was turning a bunch of engineers into business people with an engineering competency."

For Wattelet, focus and flexibility have been key for a company with 100% of its attention in the power sector. Transmission and distribution work "has gone up 300% to 400% over the past five years, and it is going to stay there for the next three to five years," he adds. "You either go with the flow or disappear like the dinosaurs."

Anticipating the future is something building contractor Swinerton Inc. has done since its founding in 1888 by a Bakersfield, Calif., brick mason just after a devastating fire there, says CEO and Chairman James Gillette. The firm then moved to San Francisco where its innovative reinforced concrete buildings "were the only ones to withstand the 1906 quake," he says. "We got lots of work."

|

| In 1907, 19-year-old Swinerton linked its growth to San Franciscos as it helped rebuild the earthquake-ravaged city. (Photo courtesy of Swinerton Inc.) |

Swinerton went on to build much of the San Francisco skyline until the Great Depression, when hard times forced it to "almost shut its doors," Gillette admits. But previous management "decided instead to hire the best people from other firms going out of business," he says. While diversification into defense work went bust, market switches have helped Swinerton survive disastrous real estate recessions over the years and grow from $230 million in 1992 to possibly $2 billion this year. "A few years ago, work was 80% negotiated. Now its 60% hard bid," says Gillette, who remains Swinertons chief financial officer after 20 years.

The contractor also diversified ownership in the mid-1970s. "We began adding six to seven employee shareholders a year," says Gillette. "Now we add 50 to 60." He also recognizes the changing work force. "The white male hasnt disappeared, but he has a lot more company," he notes. The firm has become more involved in efforts to promote industry careers in urban schools.

But Swinerton is staying away from too much risk. "We dont try to take on huge projects that will kill us," says Gillette. It also has shied away from international work. "Why go so far to lose money?" he asks.

Focusing on risk analysis has been good for Parsons Brinckerhoffs bottom line as well as its engineering work since engineer William Barclay Parsons hung out his shingle in 1885. He and future partner Henry M. Brinckerhoff both pioneered design and construction techniquesParsons refined cut-and-cover subway construction and Brinckerhoff invented third-rail designbut the company that bears their names has weighed risk carefully over the years.

"We dont take risks that are too big," says CEO Thomas J. ONeill. "People push out there and try new things, but they also have to know when to pull back." PB was scorched in the 1990s by a $90-million cable installation contract that went awry when the owner owed the firm $22 million. The account eventually was settled but "it made us wiser about how to write contracts," says ONeill. Such experiences and better understanding of new markets and clients have allowed PB to weather industry ups and downs over 118 years and become a $1.35-billion-a-year global force. "Our foundation is U.S. transportation, but we are not solely dependent on it," says ONeill.

PB still "has no trouble attracting good talent," says ONeill, although he worries that slowdowns in big projects could have an impact. "People have to have challenging jobs. I worry about this short term," he says. "Even though the needs are out there, the pipeline is not as robust." Committing to private ownership, despite the lure of public capital in the past, also was a good decision, ONeill insists. "If we want to be in business for the long term, we cant focus on short-term profitability," he says.

But other firms have found fame and fortune on Wall Street, including Chicago Bridge & Iron Co. The industrial contractor dates back to 1889, but its specialties soon changed with new technology and emerging energy and water markets. In 1996, CBI was wooed to merge with industrial gas manufacturer Praxair Inc. but was spun off a year later. "They had promised from day one they would not try to run the E&C business," says CEO Gerald Glenn, who took early retirement from Fluor Corp. to join CBI.

While employees initially worried, it seems that public ownership has worked for CBI, based in The Woodlands, Texas. Glenn says that a February 2003 decision to split the firms $32-per-share stock to increase the dividend worked out. One year later, the share price was back to $32, he says. Investors are happy as well with CBIs $2 billion in annual revenue and the firms debt-free balance sheet.

|

| McHugh pioneered cranes in 1960s Chicago but didnt fare as well overseas. (Photo courtesy of James McHugh Construction Co.) |

Keeping a realistic focus on core competencies also is a running theme for $248-million-a-year James McHugh Construction Co., Chicago. A general contractor specializing in high-rise concrete, the firm has since 1897 built several key concrete landmarks there, including Marina City. The twin 60-story apartment towers was a daring project in the early 1960s. "We were just about the only ones willing to do it," says 78-year-old James P. McHugh, the firms third-generation CEO. McHugh also branched out overseas with a Moscow office in 1992, but quit by 1998.

Boise-based architect-engineer CSHQA evolved from many partnerships since it began in 1889, but focus on the bottom line was still a century away. "We began to move from the art of architecture to the business of architecture," says President Jeff Schneider. "Out of that, we moved to relationship-based marketing." The firm also refined its ownership profile. "We now have 19 shareholders and theyre a stratified age group and ownership level," he says. "If you get a disgruntled person and he or she leaves, you still have critical mass."

|

| Detroits growth kept 1920s SmithGroup drafters busy for a while. (Photo courtesy of the SmithGroup) |

SmithGroup found critical mass by moving to Detroit soon after its 1853 start, benefitting from the citys growth as an industrial center, says Carl Roehling, CEO. "Technology coming out of the auto industry drove the firm," he says. SmithGroup almost tanked when the Great Depression hit, but survived on public-sector work and "some partners who maintained the talent," says Roehling.

The lessening interest of founding family members in the firm hastened a change to employee ownership by the 1960s. Investment in the future is key. "We probably take less money out of the firm than others do," says Roehling. "Its important to leave it there."

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment