|

| (Photo courtesy of the courtesy of the Ironworkers Union) |

Hunt occasionally is mistaken for the former president and will sometimes play along with his staff when they have a little fun with the autograph seekers. But Hunt has a bigger missionrevitalizing a union that has been rocked by scandal and seen its market share slide along with almost every other building trade union.

The ironworkers leaders recognize that they must change old ways of doing business in order to remain a vital part of the industry. The sagging economy, competition from the open shop and a new, younger breed of workers and employers have changed the face of construction. "Our industry has to be more competitive to gain market share," Hunt asserts. "We have to make our contractors more competitive. If they dont have a job, theres no job for us to work on."

The international union and some of its locals are leading the evolution. One of Hunts goals is to increase membership by 5% annually and improve market share from the average of 20%. In 2001, his first year in office, the union met the membership goal, but since then, "weve stayed relatively even," Hunt says. Current membership is 102,526, says Bernie Evers, executive director of organizing. That is up from 96,577 in 1993, but far less than the 142,342 members in 1983.

Hunt is concerned that the membership numbers could slip again, a reflection of the lackluster economy and the slowdown in construction.

|

|

LEG UP ACES program is one that Hunt started to help train organizers and union officials. (Photo by Michael Goodman for ENR) |

Change is coming, but it often is slow as long-standing practices and philosophies must be altered. "No one likes change, but change has to happen or [the union] wont exist," says Charles Wright, a business agent from Local 7 in Boston. Wright was one of 14 organizers who recently attended a training class at the George Meany Center for Labor Studies in Silver Spring, Md., as part of the unions Analyzing Construction Employers Strategically program (ACES). Hunt started ACES in 2001to teach organizers to follow owners and secondary targets. Representatives from each of the unions 22 District Councils attend the week-long course, which combines classroom training with practical skills. As part of the program the "students" visit a job-site and make house calls to prospective members.

This is only one program that Hunt has initiated in his nearly three years as general president. Besides increasing the competitiveness of union contractors, Hunt pledges to streamline the organization of the union, raise the ironworkers political profile and improve relations with management.

To achieve these goals Hunt has launched the Ironworker-Management Progressive Action Cooperative Trust (IMPACT), a labor-management joint trust which Hunt calls "critical to the future of our union and our industry." IMPACT aims to increase jobs and market share for both workers and employers. "The trust will develop a safety program that will include workers compensation and general liability insurance, a substance abuse policy and an alternative dispute resolution procedure for contractors who are signatories with local unions that have added IMPACT to their collective bargaining agreement," says Eric S. Waterman, IMPACTs chief executive officer. In its first six months, about 50 Locals have signed up for the program. Others may consider the trust when their contracts are renegotiated.

Hunt is a leader willing to take chances to improve the state of his union. He plans to reinstitute regional conferences that were last held in 1989, streamline the number of district councils to 18, and start a new multi-state local devoted exclusively to rebar. "Were going to try and do something to save our organization," he says. Safety is another top issue for the union, whose workers are often called the "cowboys of the skies." Most injuries occur during steel erection, says Hunt. The union has taken the lead in training workers, contractors and Occupational Safety and Health Administration inspectors in the new federal steel erection standard. "Our program is an awareness program," says Hunt. The challenge is to undo the bravado that leads some workers to discard their hard hats or decide not to tie off, he explains.

|

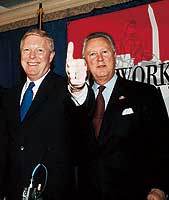

| OLD PALS Hunt (right) was an early supporter of Gephardt (left) (Photo courtesy of the courtesy of the Ironworkers Union) |

The union chief also believes it is important to elect state and federal candidates who support issues key to workers. His long-time friendship with presidential candidate Rep. Richard A. Gephardt (D-Mo.) has raised the unions political profile, as the ironworkers were the first labor union to endorse Gephardts White House bid.

Hunt is aware that not all of his ideas will be fully embraced by members. "If you want someone who wont do anything, then elect him at the next convention," Hunt told a recent ACES class.

It was a difficult time when Hunt, 60, ascended to the top post of the International Association of Bridge, Structural, Ornamental and Reinforcing Ironworkers in February 2001. The union was under a legal and public microscope, with widespread allegations of internal corruption. Top officers were forced out and Hunt, general treasurer since 1998, was elected to the top post by the General Executive Council. Six months later, he was elected to a full, five-year term at the unions convention. As president he has received relatively good marks, so far. "Hes not afraid of being innovative," says Wright, the Boston business agent.

Hunt also receives praise from other union leaders. Terence M. OSullivan, president of the laborers union, says Hunt "has a solid vision of where he wants to take his union and hes putting in place the programs, such as IMPACT, to do it. The ironworkers training initiatives and their efforts to recapture mar-ket share are great examples for every union," says OSullivan. Edward C. Sullivan, president of the AFL-CIOs Building and Construction Trades Dept., commends Hunt for improving communications with the unions 235 locals. Hunt is informing the rank-and-file about the changes hes making and "that goes a long way," says Sullivan.

Hunts decision to post the unions federal financial disclosure forms on its Web site has won kudos from Labor Dept. Secretary Elaine L. Chao. "I wish more unions would follow your lead and demonstrate their commitment to transparency and accountability," Chao said in a letter to Hunt earlier this year.

But the union chief also has his critics. Joseph Blaze, the business manager, financial secretary and treasurer of Local 55 in Toledo, Ohio, challenged Hunt for the presidency at the 2001 convention. Blaze says hes adopted a wait-and-see attitude. "Im going to be fair to Joe Hunt," he says. "Im not going to judge him after two years; its a five-year term. When you make changes, the results are never immediate, so it really remains to be seen." However, he admits that the union "is far better from where we were headed prior to the election."

Hunt didnt expect to make ironworking his career when he was growing up in St. Louis. His grandfather, father and older brother were in the trade and held offices in Local 396. Hunt worked summers as an ironworker but dreamed of college and a different career. "It was in my blood, I guess," says Hunt, who has worked in most sectors of the craft, particularly rebar and structural. He quickly ascended the leadership ladder, serving as business manager of Local 396 and then going to Washington, D.C., in 1983 as a general organizer. He held a number of posts with the international until 1990 when he returned to St. Louis and was elected president of the district council there. But while working at the unions headquarters, Hunt observed the operation, and like so many others, he would "sit back and critique his boss," wondering what he would do differently.

Local 512 in Minneapolis-St. Paul has heard Hunts message about the importance of organizing. The local, one of seven that comprise the District Council of the North Central States, enjoys a market share that hovers around 90%. "Theres never been a major job in this town thats been nonunion," says Business Manager Charlie Witt. Robert T. Heise, president of the Minnesota chapter of the Associated Builders and Contractors, says that nonunion contractors have a bigger share of the market farther away from the bigger cities.

Local 512s strong hold on the market also has made it difficult to convince the 1,300 members that organizing and recruitment are necessary. "We keep working on members, but some are resistant," Witt says. Many believe that if they had to go through the apprenticeship program, every new recruit should also go through the training even if that worker has 15 years of experience with a nonunion contractor.

|

| MARCHING ORDERS Struss has a plan for local unions. |

Witt and the other officers try to educate the members about why organizing is important for the health of the local. Part of the education is to teach members that recruiting nonunion workers will not threaten their ability to work. If the local controls a bigger share of the market, it will reduce each individuals cost to run the local, explains Gordon T. Struss, a former 512 business manager and now a general vice president of the international union and president of the district council. In June, Struss informed each business manager in his district that by June 30, 2005, each local union needed to show a 15% annual growth in membership through apprenticeship, a 5% membership growth per year through organizing nonunion workers, employ a full- time organizer, sign two new contractors per year and implement a market recovery program. Unsuccessful locals may be merged, he says.

Local 512 is learning to market itself, creating print and radio advertisements, attending high school job fairs and reaching out to community groups. Earlier this year the local hired a full-time organizer and expanded its market recovery program. "Its pretty aggressive," says Witt. "We dont want to drive [nonunion]contractors out of business, we want to get them on board," he explains. Adds Struss: "We look at the jobs [coming up for bid] and target those where we think we can get some inroads."

Recruiting women and minorities sometimes is easier than keeping them, says Struss. And union membership no longer is reserved for sons, brothers and nephews, as it was in the past. The local gets phone calls from angry members when their relative does not get accepted into the apprenticeship program, says Struss. "Thats a real indication of fairness," he explains.

|

| BUILDING TALENT Grayson's three-year-old training center gives the union flexibility. |

The locals three-year-old training center has allowed it to expand the size of its apprenticeship classes and offer more training and safety courses for its members. "Having our own building gives us the flexibility to do customized training," says Al Grayson, coordinator of the Twin City Iron Workers JAC Joint Labor & Management Training. Mobile centers offer hazardous materials training and metal building training.

Some of the steel erection contractors that Local 512 does business with see improvements, particularly in safety and training. Rodney Skogen, one of the owners of Amerect Inc., Newport, Minn., says the apprentices are "well trained and do a good job in the field." Communications also have improved between the local and its contractors, he says.

The locals leadership is "open minded and willing to listen to our side of the issues," says Stephanie Jochims, president of Western Steel Erection, Orono, Minn. "They understand that without us, they dont exist." Jochims, who also is president of the Minnesota Steel Erectors, says she thinks IMPACT has potential, but she and other contractors are "wrestling with where the funds will come from" to pay for the program.

Jochims was impressed with Hunts presentation at a recent IMPACT meeting, especially his commitment to "project a better image" of ironworkers. Still, contractors are concerned about a variety of issues, particularly the cost of workers compensation insurance. Jochims also praises Local 512s commitment to safety and training. "Were seeing better-trained apprentices" coming out, she says.

(ALL OTHER PHOTOS BY SHERIE WINSTON FOR ENR)

he president and his entourage enter the Washington, D.C., restaurant and head to their table. A small cluster of patrons, probably tourists, does a double take and then stares. "Is it him?" one of the crowd asks a member of the entourage she mistakes for a Secret Service agent. "Yes," replies the aide, aware of what will come next because this is not the first case of mistaken identity. The women ask to meet the president and the aide obliges. But it is not President Bill Clinton that they meet. It is General President Joseph J. Hunt, head of the ironworkers union.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment