|

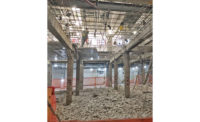

| MEMORIAL HALL Architectural gem gets costly, structurally unobtrusive retrofit. (Photo courtesy of William Porter) |

For years, many national contractors steered clear of construction work at the University of California's Berkeley campus, citing contracts that even school officials described as risky and unfair. But when the university launched a $1-billion-plus seismic retrofit program four years ago, they knew they needed moreand more qualifiedbidders to save taxpayer money. So they began experimenting with contracting strategies new for the public campus. Unfortunately, the experiment may not be working as well as expected financially, based on experiences on UC's first seismic project now under way. Contractual disputes appear to be as complex as the task of removing the foundations of an historic brick building just yards from a dreaded fault.

In a 1998 industry speech, Jeffrey Gee, UC-Berkeley's former director of design and project management, promised "a big paradigm shift in the way we've been doing business with contractors." The campus' adherence to lump-sum contracting and hold-harmless clauses kept many of the area's most highly qualified designers and contractors away and often escalated project costs. He sought instead to employ a blend of construction management and general contracting that would allow team members to collaborate better and identify pertinent risks sooner.

To launch the approach, Gee, now a vice president at San Francisco-based Degenkolb Engineers, chose a high-profile projectthe challenging retrofit of UC's nearly century-old Hearst Memorial Mining Building, used for instruction. The technically complex upgrade "was the first major project in the shop...that lent itself to a way of thinking of a new model of delivery," adds Robert R. Gayle, a former UC project manager on the structure who succeeded Gee.

But results since work began in the 1990s have given participants an education in the realities of construction. Originally estimated in 1993 to cost $51.2 million as a base isolation project "of average complexity," according to UC officials, the project rose to $67.6 million in 1997 for more historic preservation. Last July, the total was increased to $80.6 millionand counting. Retrofit completion, set for last October after an extension was granted, is now months behind. Plans call for work to finish in July. But the Oakland office of Turner Construction Co., the project's CM-GC, may face liquidated damages of $5,000 per day since the Oct. 1 deadline.

HAT TRICK. Built on more than 70 change orders so far, the four-story mining building rests on an elaborate new foundation. Without the luxury of any preexisting steel columns to work with, crews placed the building on a grillage of cast-in-place concrete beams set on base isolators. "This is an amazing hat trick for the university," says Brendan Kelly, a senior associate in the San Francisco office of NBBJ, which designed the renovation. In January, UC officials held a ceremony to symbolically unlock the isolators, to cushion all the weight of brick walls up to 7 ft thick.

Unlike other base-isolation retrofits elsewhere, the project lacks any substantial new framing from the ground floor on up, despite concerns for safeguarding the building's architectural history.

Team members show off the renovated Memorial Hall atrium, with its vaulted ceiling and Guastavino ceiling tiles like those in New York's Grand Central Terminal. But they admit that major construction problems happened below grade. Crews excavated the building's basement in mining-like conditions during the wet 1999-2000 winter. "The logistics of material movement under that building were quite challenging," says Grant Griffanti, Turner's senior project manager in Oakland, Calif. Turner ended up mired in delaysand working through the process of alternate dispute resolution.

|

| (Photo and graphic courtesy of NBJ/Photo Marion Brenner, photo manipulation by Nancy Soulliard for ENR) |

Although Griffanti declines to elaborate on the substance of the dispute with UC, he says, "We feel that the contract we signed says one thing and they feel it says another." But he and colleagues hesitate to air much dirty laundry in what they view as an architectural, structural and construction tour de force. "It's going to be a very successful projectI wouldn't want the contractual issues to put a cloud over the entire performance," says Danny Cooke, Turner's operations manager. "It's too soon to tell from a commercial aspect."

Turner played the role of guinea pig in UC's adoption of the CM/GC method. In November 1998, the firm began building the Hearst project on change orders, self-performing 10% and receiving 7.1% for base amount "amendments" but just 5% fees for "scope changes." UC's Gayle denies that the fee scheme encouraged campus officials to low-ball the base sum. He points out that the current dispute does not concern the fee scheme; instead, delays are due to "excavation and demolition in very constrained spaces." Last August, Mike Iker, Turner's regional sales manager, told ENR: "The interesting thing about that job is it's like working in the bowels of hell."

But UC regents now warn that "additional campus funds beyond the [2001] budget increase currently requested will be required to sustain construction progress to completion under the conditions of dispute now prevailing."

The regents gave several reasons for last year's budget increase. They cited "numerous unforeseen conditions" as in the roof and floors; more "sub-surface rock beyond that anticipated"; "uncompetitive market conditions" in the Bay Area's subtrades back in 1998 with bids that "substantially exceeded the pre-construction cost estimates"; and an extent of work that "had not been fully defined in the architect's contract documents."

From the start, Gayle and others wondered what to expect in a 135,000-sq-ft building that first opened in 1907 with minimal foundations: spread footings, with some walls directly on rock. Unknown conditions also existed above. With a 183- x 186-ft footprint, the light-filled building originally contained spaces tall enough to accommodate mining rigs. But a 1948 renovation inserted an additional 10,000 sq ft of floor space that has now been removed. Without two new wings that add back the 10,000 sq ft, the building lacked any vertical framing other than unreinforced walls.

|

|

KNIT Needle beams provided temporary support, threaded through old brick. (Photo courtesy of Turner Construction Company) |

Designed as a memorial to 19th-Century mining mogul and U.S. Sen. George Hearst, the building's design reflected a confidence in masonry's rigidity. But according to local legend, students discovered the highly active Hayward seismic fault while practicing quarrying operations next to the building. Seismologists now predict a magnitude 7.2 quake on the fault with ground accelerations of 0.7 g. To keep retrofit costs down, UC decided to accept the likelihood of significant but hopefully reparable damage to the building's nonstructural systems in such a quake. Still, they directed engineers to keep the structure occupiable after a magnitude 6 quake with 0.48 g.

The retrofit posed considerable risks. Above grade, engineers pretty much left the structure alone except to add perimeter beams to secure floors to walls. All the structural work cost approximately $25 million, yet "it's what we call a bare' building," says Harold A. Davis, principal structural engineer in the Oakland office of Rutherford & Chekene. He considers it the first such retrofit without any new shear walls, bracing or other such strengthening, and one of the few with a foundation replacement.

|

Davis proceeded with an awareness of cost overruns on other base isolation retrofits, where lead engineers specified means and methods for transferring a building to a new foundation. For the Hearst retrofit, he and UC decided to try to save money by relying on the contractor's judgment.

But the university took its time in choosing whom to hire and how, critics contend. "This is the first project on campus to use the CM/GC method...it wasn't adopted in a sufficiently timely manner," UC's Gayle admits. Rather than hire a CM to provide input from the start of design in 1996, UC waited until 1998 to solicit bids, then looked at fees proposed by Turner and Rudolph & Sletten, Foster City, Calif. Rejecting them, UC started over with a revised definition of "general conditions," meaning the use of onsite managerial staff. Turner then submitted a bid of 7.1% for fees and general conditions, compared to R&S's 11.16%.

Not that UC officials gave Turner time to provide preconstruction services. "There really wasn't a CM function; there wasn't that opportunity," Gayle says. But he emphasizes that using the CM/GC method opened up more opportunities for a dialogue with Turner about how best to transfer the building onto a new foundation.

Former construction chief Gee contends "there were opportunities potentially to define some middle ground, to finish in December instead of this summer, and to make everyone a little more whole than they will be now." But he still sees much value in the project delivery method. Although it failed to work as well as possible because the campus did not hire Turner soon enough during preconstruction, CM/GC can help contractors, especially those that self-perform just a small portion of work, to assess risks sooner and adequately prequalify low-bid subcontractors, says Gee.

|

| Base Isolators (left) sit on new pile caps among temporary steel (top left) that underpinned building for new basement and first floor (right). (Photos courtesy of Turner Construction Company) |

Since letting that contract, the campus has used the method on four other retrofits with a combined value of $75 million. All have been under Rudolph & Sletten's control, and all have remained within budget, Gayle says.

"To me, it's a win-win situation for everyone involved," says Ken Brickwedel, Rudolph & Sletten senior project manager on campus. The CM/GC method makes public-sector work "more of a private-sector, streamlined project," he says. Although campus and company officials have not agreed on all requests for change orders and time extensions on other campus retrofits, CM/GC has worked well for handling unforeseen conditions such as buried sheet piles, Brickwedel says. By giving responsibility for preconstruction services to the contractor rather than to a third-party cm, the approach has fostered a non-exploitative relationship with UC.

On the Hearst building, the once hellish site conditions have given way to signs of progress. Crews excavated as much as 28 ft to add a new first floor and basement and drilled in 687 concrete-filled steel piers. Despite few opportunities to make up lost time, they underpinned the building and installed 132 high-damping elastomeric rubber base isolators, each 30 in. high and designed to shear horizontally as much as 28 in.

Pleased with the work and the minimal cracking of masonry, Gayle praises the "extremely productive relationship" between UC and Turner in a "well-behaved dispute." While he concedes that "there are significant dollars at risk," he is unconcerned about possible fallout. "I'm not aware of any deterrent effect," he says. "We want to be seen as a good partner." Gayle says other A-list contractors such as Charles Pankow Builders Ltd. and M.A. Mortenson Co. now do business with UC-Berkeley. "These are names that you would not have seen on our campus 10 years ago," he says.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment