...two jobs. Recently, I was able to negotiate a piece of the pie [in the form of profit sharing] and a more secure future going forward.” He adds that when he had an eight-hour-a-day job, he had even less job satisfaction.

Another veteran project manager says he believes attitudes about overtime hours have changed. “I used to work for contractors who would ‘swap’ hours and give some time off during the week following the bid,” he says. “They would say, ‘You worked overtime or on the weekend for this bid, so take a couple days off and we’ll call it even.’ ”

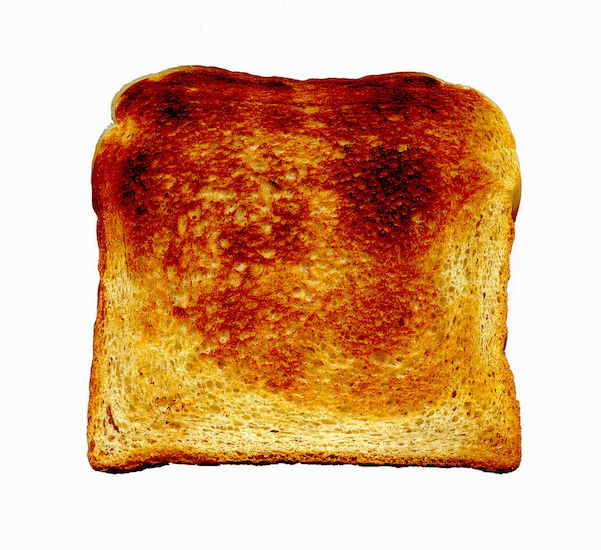

But the manager says, “Now, the contractors I work for tell me, ‘If it takes 60 hours a week for you to get these bids out, you are going to work that and be happy you have a job.’ After years of this, I feel like burned-out toast and will be so happy to retire from this heck.”

Whether new generations of construction professionals will be willing to accept many current workplace conditions isn’t clear. “I suspect that my generation is going to have less and less of these single-focused individuals,” says one 30-year-old contractor project manager in another blog post. “We have more outside interests that compete with work for time. Living a balanced life is replacing the mantra of getting a good job and working hard for the same company for an entire career. An occasional 60- to 70-hour week is fine, even welcome at times, but when it becomes required just to navigate the entire building process, something is going to give.”

There is a rich history of the exploited and the ambitious working to unhealthy excess. From Henry Ford’s rigidly policed assembly-line workers to the fanatical, round-the-clock Wall Street dealmakers, business has involved superhuman exertions. In 1992, Harvard University economics professor Juliet B. Schor popularized the idea that work was squeezing out leisure and that working hours were rising, not falling, as some would have assumed—and this was all years before anyone had uttered the word “Blackberry.”

The deadline-driven, contentious construction industry could be moving into a class of its own. While managers tend to think of themselves as hardy individualists and not typical American “organization men,” observers and participants wonder how many ever come forward to say they are putting in too many hours under too much pressure and that it is killing them. “I see a lot of self-sacrifice, for families,” says Darnell.

Employers generally understand that key employees, if not all staffers, should not be treated like racehorses to be driven to the finish line.

How far should employers go? How much can an engineer or project manager stand? It should never come down to that in an ethically run business.

John Rowan, a professor of philosophy at Purdue University, West Lafayette, Ind., writes that employing people implies not just fair pay, workplace safety, due process and privacy. In a 2000 Journal of Business Ethics article, he says, over long periods, ethical employers do not regularly deprive staff of the time needed to rest or be with families. That requires some consideration of the employee’s rights when, for example, meeting the deadline to finish a project requires ordering the staff to work all through the night, without sufficient breaks. Bonuses and incentives may help, but there should be some permission given by the employee, or it’s wrong, according to Rowan.

If the ethical case isn’t enough, most research shows that burned-out workers are not as productive and effective, make more mistakes and deplete morale with their cynical and dejected feelings.

Morale Free Fall?

Construction employers don’t want to allow morale to go into a free fall. In the human-resources department of one Southwest region structural engineer that has seen layoffs and pay cuts, the effects have metamorphosed into a company-wide malaise, according to officials who requested anonymity.

“Our employees don’t seem to be as happy as they use to be,” says the firm’s human-resources director. “They are not apt to participate in company functions. We have a great workforce, but nobody’s come into HR and admitted they’re experiencing stress … we just see it in the way they interact.” The staffers, she adds, tend to keep close to their own group.

Employers place engineers in an especially stressful dilemma, sometimes asking them to work outside their...

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment