Novel Pivoting Concrete Core Saves San Francisco Developer $4 Million

In a back-to-the-future scenario, the structural engineer for the seismic retrofit of a 1962 steel moment-resisting frame in earthquake-prone San Francisco fashioned the office building's high-tech lateral system after an ancient Japanese pagoda. The building's 14-story pivoting spine—equivalent to a pagoda's wooden "shinbashira"—turned into a $4-million-plus silver lining to a recession-related hiatus for the $110-million gut renovation and expansion of 680 Folsom Street.

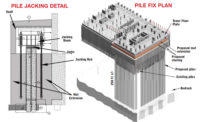

Instead of a tree trunk pivoting in a well in the ground, the ultra-modern shinbashira is an 8-million-lb structural concrete core. The 232-ft-tall heavyweight sits on a single sliding friction-pendulum bearing, 3.5 ft in dia. The bearing can slide like a marble in a bowl.

Thanks to the 4.5-ton slider bearing assembly, the spine—a hollow 30-ft square in plan, except for a solid, reinforced concrete sacrum at the base—has freedom to pivot during a quake. Like a shinbashira, the four-walled core rests on the bearing without a fixed connection.

In a quake, the system acts like a Ring Toss toy. All the rings—floors—move with the stick—the rigid core—and distribute interstory drift over all the floors.

The pivoting spine acts as a mode shaper, forcing uniform displacement in the moment frame and engaging the upper floors to dissipate seismic energy. "The system changes how a building will react in an earthquake," says Steven Tipping, president of structural engineer Tipping Mar (TM), which authored the scheme. "The Japanese discovered this [behavior] about 1,500 years ago."

TM developed the rigid pivoting core through performance-based engineering using non-linear-response history analysis. The goal was to meet current California Building Code provisions.

The novel scheme—the result of a value-engineering exercise in 2010—forced an architectural and structural redesign of the building interior, which was permitted before the work halt in 2008. But the more than $4 million in savings made the extra design work worth it, says Matt Field, managing director for 680 Folsom's developer, TMG Partners.

The gut renovation, designed by the building's original architect, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), also added two stories and a new curtain wall.

The modern pagoda replaced TM's original seismic-retrofit scheme, which consisted of two post-tensioned concrete walls, each an I-shape in plan, around the original stairwells at each end of the architectural core. The scheme was similar to a system TM devised for the year-old San Francisco Public Utilities Commission Building.

The bulk of the savings from the revised scheme came from cutting out a core. That step reduced materials and labor costs and sliced 10 weeks off the 100-week construction schedule, says Mike Danska, senior project manager for Plant Construction Co., the general contractor.