Cliff Schexnayder / ENR A shielded TBM would be trapped, experts warned. |

Even though the 5-meter-dia, unshielded Robbins gripper TBM is tunneling through one of the lowest reaches of the Andes, it is still one of the deepest tunneling projects in the world. The Gotthard Base tunnel in Switzerland, with 7,588.6 ft of overburden, is the deepest.

|

There are big differences between the two projects, but a key one is that the Gotthard project’s four Herrenknecht gripper TBMs are shielded and the $14-million Pacha Mama is not. Experts who analyzed the plan for design-build contractor La Concesionaria Trasvase Olmos S.A., which is comprised solely of the Brazilian engineering and construction giant Odebrecht, judged that extreme pressure and many microfissures and faults the TBM will encounter inside the mountain would make the rock swell and shift enough to trap a shielded machine. One of the Gotthard machines did become wedged in 2005. It took five months for work crews to free it.

Cliff Schexnayder / ENR Bracing helps counter deformation.

|

Other deep tunnels bored by Odebrecht in the Andes—notably the San Francisco tunnel project in Baños, Ecuador—have used double-shielded TBMs to protect the machine from possible cave-ins. That wasn’t an option for this project, according to project leader Biaggo Carollo.

“Double shield is to help protect the TBM but in this situation it could cause it to become stuck,” he says. “With the type of pressures we are dealing with...we would lose the machine.”

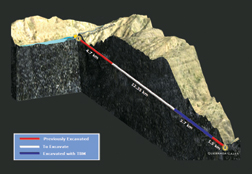

Odebrecht engineers estimate a double-shield TBM would be able to bore only 12 meters before the pressures of the rock would immobilize it. The unshielded TBM, by contrast, with its 35 17-in.-dia disc cutters, can continue to move forward regardless of the deformation behind the cutter head. It also has the ability to overbore the tunnel diameter by 50 mm, if necessary.

“Going in we wanted to protect ourselves from the risk,” says project director Erlon Arfelli, explaining the choice of an unshielded machine. But he adds, “In truth, no one knew exactly what a job like this would involve.”

| + click to enlarge |

|

Odebrecht

|

Odebrecht

|

Cliff Schexnayder / ENR Building access road to tunnel head required steep retaining walls.

|

An Old Dream

The tunnel is part of a 20-year, $190-million effort to accomplish a plan that dates back to the early 1900s. The Andes are an immense barrier that prevents rain from moving from the jungle regions of northeast Peru and Brazil toward the dry coast. The vision of conveying water from the Atlantic side of the mountains to the fertile but dry Pacific side has enticed Peruvian leaders from one administration to the next. It was only after the government of Alejandro Toledo relaunched the project on the basis of a design-build-operate, public-private partnership concession, and enlarged it with a hydroelectric component in 2001, that the current, promising effort took shape.

Odebrecht won the concession in July 2004. The project became the first in Peru financed through a PPP-style system, with federal support of $77 million.

When complete, the tunnel will be part of a system to annually transfer more than 2 billion cubic meters of water from the wet to the dry side of the mountains. The project includes damming the Huancabamba River near the village of San Felipe with the 43-meter-high, roller-compacted concrete Limón Dam to form an impoundment reservoir, Water will then be diverted through the mountains to the usually dry Olmos River on the Pacific side. The first phase, which involves construction of the dam, excavating the tunnel, moving a gas pipeline and building an access road, is under way.

Water should begin flowing by March of 2010. It will irrigate more than 56,000 hectares of scrubland along the Pacific Coast north of the town of Chiclayo.

Later phases will include construction of at least two more tunnels and two more dams, as well as an extensive canal system on the Pacific side to distribute the water on the coast. Two hydroelectric generation facilities capable of generating 600 MW are also planned.

Pacha Mama, which means “Mother Earth” in the local Quechan language, began work in February 2007. Despite delays in December due to bursting rock, and...

n the mountains of Peru a tunnel-boring machine named “Pacha Mama” is grinding through the heart of the Andes under rock as deep as 6,890 ft. It is carving away at a 20.2-kilometer-long tunnel through the South American Continental Divide to deliver water to arid coastal farmland. Related Link:

Related Link:

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment