Faced with sprawling growth in the greater Seattle area, King County water officials have capitalized on the population’s environmental awareness to push through a $1.7-billion wastewater treatment system that could become the country’s showcase for advanced secondary treatment. Taking advantage of technological advances that lower energy needs and produce an effluent clean enough to be sold for nonpotable use, the county’s division of wastewater control is building a 36-million-gallon-per-day plant, the largest in the U.S. to use membrane bioreactors, borrowing from systems developed to treat drinking water.

King County Wastewater Treatment Division

|

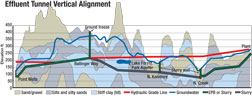

The Brightwater plant, located 11 miles north of Seattle in Bothell, will handle wastewater flows from King County’s northern reaches and part of neighboring Snohomish County. Flows will be delivered to the plant through a 13-mile conveyance tunnel now being bored under three tunneling contracts through soft ground of mostly glacial till. The 16-ft-dia. tunnel will do triple duty. It is being fitted with a force main to handle raw wastewater flows, boosted on its way to the plant with a 170-mgd pump station. Other pipes will deliver reclaimed water that will be sold for irrigation or industrial use, and treated effluent that will be discharged through a new outfall to 400-ft depths in Puget Sound. Sections of the tunnel are also designed to handle excess stormwater flow. By 2040 the plant, designed by CH2M Hill Cos.’s Bellevue, Wash., office, will be expanded to provide average daily treatment capacity of 54 mgd.

But the system swings on the MBR system, which treats secondary effluent to levels greater than conventional activated sludge systems to produce effluent greatly exceeding federal standards. “It costs more, but allows us to go to a higher level of treatment and even supply high-grade water effluent to local golf courses and provide for industrial uses,” says Christie J. True, King County water treatment director.

|

“It costs more but allows for a higher level of treatment and supply of high-grade effluent.” — CHRISTIE J. TRUE,

WATER TREATMENT DIRECTOR |

Key to the project’s economics was the state Dept. of Ecology’s approval to build the MBR system for only base loads, an exception from its rule requiring full secondary treatment for all flows. Peak flows in Brightwater’s service area are estimated at 170 mgd by 2040. Stan Hummel, county wastewater capital projects supervisor, says providing MBR treatment for peak flows would have sent costs soaring, partly because of MBR systems’ operating power needs. Instead, the county’s team proposed a strategy to split flows during wet weather: Base loads will be treated with MBRs and excess flow will be split, undergoing chemically enhanced primary treatment only. The two will then be blended to a quality level that still exceeds state and federal standards, and discharged through the outfall.

King County Wastewater Treatment Division Rail-mounted tower cranes provide efficient hoist capacity over large work area.

|

“It still translates to a total reduction of 1 million lb [of total suspended solids and BOD],” says Hummel.

Hummel says MBR’s ability to fully oxidize ammonia was another key to gaining state approval because some areas of Puget Sound show low levels of dissolved oxygen. Brightwater’s effluent will meet state Class A standards for reclaimed water.

The county’s comparative evaluation projected a full-flow conventional activated sludge system would cost $469 million, compared to $467 million for an MBR system based on splitting flows. The MBR option produced a reduction in the project’s tank footprint by 30% because secondary aeration tanks are not needed. The reduction in number of tanks also reduced the volume of foul-smelling air to be treated, and fewer odor-control units than a conventionally sized plant.

“If the MBR process were sized to treat peak flows, it would have been significantly more costly than the split-flow arrangement,” says Hummel. “On a per gallon basis, Brightwater is $15.06 per gallon of constructed capacity, comparable to a highly mitigated treatment facility in an urban area.”

|

|

The county is funding construction from sewerage rates and connection fees with no state or federal money included. “We’ve seen interest rates on the money we’ve had to borrow go from 1.5% to 8%,” says True. “We’re watching that very closely.”

The Brightwater plant augments county’s two others: South Plant in Renton, on Lake Washington, and West Point, in Seattle on Puget Sound. “Neighbors near those plants did not want any expansion near their homes,” True says.

| + click to enlarge |

Nancy Soulliard / ENR Source: King County

|

County officials were proactive in siting Brightwater and winning approval from local residents over location and design. The plant is being built on a 114-acre site at the bottom of a 40-ft slope formerly used as a junk yard. Hoffman Construction, Portland, Ore., working under a $300-million general contractor/construction management contract, rebuilt 40 acres of wetlands on the north side of the site as a mitigation measure. It is moving about one million cu yd of soil to prepare the site and create “a visual buffer” for residents. The county also is spending $65 million on an odor-control system that officials say will ensure the plant to be a good neighbor.

Residents also were concerned about seismic issues because the site is near an active fault line. As a result, parts of it were redesigned to withstand a 7.3-magnitude earthquake.

Project Management

Bid packaging of such a large project was one of the first concerns of King County managers.

“We wanted to have an interface in packaging that would be easy to describe in the design documents and ease the contractors’ ability to go get bonding,” says Hummel. The county broke the project into two main contracts to build the treatment plant—$300 million to Hoffman to act as GC/CM for sitework and the liquids system, and $168 million to Kiewit Pacific, Vancouver, Wash., to build the solids, odor-control and energy systems.

The tunnel-conveyance system was broken into five main contracts, three for separate tunnel sections, one for a pump station and one for the outfall.

“We chose GC/ CM for the largest portion at the treatment plant site because we...

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment