... 2 million, with agriculture a major economic player. “The reality is 6 million people and hardly any agriculture,” says SFWMD’s Ammon. “We need more water supply.”

The Plan

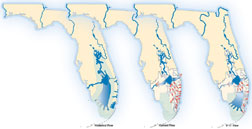

The Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan comprises 60 major components in 16 counties to capture and store as much as possible of the 5,200 acre-ft of fresh water per day that now is released into the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. Its stated goal is to “get the water right” by meeting standards of quality, quantity, timing and distribution. That means getting water of the right purity flowing in a volume, timing and distribution pattern mimicking the historical flow that created the historic Everglades.

| + click to enlarge |

|

U.S. Army Corps Of Engineers |

CERP’s aim is to remove 240 miles of barriers and route sheetflow with reduced phosphorus loading from Lake Okeechobee to Florida Bay through three Water Conservation Areas that curve gently south from the Everglades Agricultural Area. When water is abundant, it will be stored in Lake Okeechobee and in 181,300 acres of above-ground reservoirs and 330 aquifer-storage wells, then discharged in low volumes through 35,600 acres of man-made wetlands called Stormwater Treatment Areas. The treatment areas will cleanse the flow of leftover pollutants as it slowly flows south.

Under Florida’s Acceler8 program, construction has begun on one of the reservoirs, which will be the largest constructed water body in Florida. A joint venture of Bozeman, Mont.-based Barnard Construction Co. and Pasadena, Calif.-based Parsons Corp. signed a master contract with the water district in June 2006 for construction of the Everglades Agricultural Area Reservoir A-1.

The reservoir, designed by Black & Veatch, Kansas City, occupies a triangular 25-sq-mile footprint where sugarcane once grew 13 miles south of Lake Okeechobee on the west side of U.S. Route 27. A 21-mile-long perimeter embankment designed as a dam will rise 31 ft from the ground to the top of the parapet wall, normally impounding a pool of 190,000 acre-ft with a depth of only 121⁄2 ft because the dam must be able to contain storm surges, says Shawn Waldeck, the water district’s project manager. It will be built of onsite rock and soils, except for cement, says Neil Van Amburg, Barnard-Parsons project manager.

A silty sand with shells and marine deposits called Fort Thompson underlies the site and will become the dam’s core, with rockfill on the upstream shell and random fill on the downstream side. A 30-ft-deep bentonite slurry cutoff wall will control seepage.

The joint venture has completed the first three negotiated guaranteed-maximum-price phases—two seepage canals and construction of a rock-processing plant—valued at $265 million. Negotiations for the $300-million effort to build the dam, with a construction time of nearly three years, are nearly complete, Van Amburg says. The final phase will be for the 5,000-cfs pumping station and a bridge. Work is on budget and scheduled for completion in the first quarter of 2011.

Kissimmee was channelized in1960s.

|

For the 85-sq-mile Picayune Strand restoration in Collier County, planning and initial work have been completed under Acceler8, but the Corps now will take over under WRDA’s $188-million authorization.

In the early 1960s a developer drained the area, making it the southern extension of what was advertised as the world’s largest subdivision. More than 40 miles of canals channeled the sheetflow into a ditch that discharged into Faka Union Bay, and 279 miles of streets chopped the terrain into parcels for residences. The developer’s subsequent failure halted work.

The state started buying back the land in the 1980s. It was included in CERP and, in 2004, became an Acceler8 project. The land hangs like a bib from a seven-mile stretch of Interstate 75 down to the Tamiami Trail. Homes north of I-75 benefit from Picayune Strand’s drainage so maintaining flood control for them is a condition of restoring natural drainage in the south.

U.S. Army Corps Of Engineers Nearly 10 miles of canal have been backfilled to restore Kissimmee’s flow.

|

Under a design by Pasadena, Calif.-based Parsons Corp.’s water and infrastructure unit, contractors degraded 227 miles of roads throughout the site and placed compacted plugs in the Prairie Canal along its eastern edge to halt drainage. Random fill was added in 2006 to backfill seven miles of the canal.

The Prairie Canal provided only local drainage, so it could be plugged without affecting flood control, says Norm Prima, Parsons project manager. Before the project’s three other canals can be plugged, a pumping station and spreader canal for each must be built at the north end, providing 5,700 cfs of total pumping capacity.

Bids for the first one, an 810-cfs station, will be sought by the end of 2008 for completion in 2009. The other two will be completed in 2011 and 2013. The natural wetlands will recreate themselves once the canals are filled, Prima says. The engineer’s estimate for Picayune Strand is “close to $200 million,” he says.

|

| AMMON |

Quiet Progress

North of Lake Okeechobee, hydrologic restoration has advanced with little fanfare in the $634-million Kissimmee River Restoration Project, shared equally by the Corps and South Florida Water Managament District.

The Kissimmee River once wound lazily south from Orlando through 103 miles of channel and wetlands. In the 1960s, the Corps built a canal 56 miles long for flood control, and the river’s waters were channeled directly to the lake. Converting the river to a sluice destroyed wildlife habitat and injected toxic loads of farm runoff into the lake. After two decades of controversy, the Corps agreed to restore a substantial portion of the river, and work began in 1998. It aims to backfill 22 miles of the canal’s midsection and return flow to 44 miles of the river’s original channel. Almost 20 sq miles of wetlands will be reclaimed. To date, contractors have backfilled 9.9 miles of canal and restored 18 miles of the former river channel. Work is on schedule for completion in 2012.

While restoration of the ecosystem advances, so does development that threatens it. Planned communities crowd inland from both coasts. Landowners in the Everglades Agricultural Area apply for permits to replace sugarcane fields with rock quarries. Population growth creates demand for more powerplants and water supply.

Florida Power & Light Co.’s $1.2-billion West County Energy Center, a two-unit, 2,500-MW gas-turbine combined-cycle plant now under construction in Palm Beach County, is sandwiched between a former aggregate quarry and the Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge. Opponents argue that the plant’s capacity will support development that will further increase pressure on the Everglades. Completion is scheduled for 2011, and FPL has applied to construct a third unit.

Conflict continues because no one is entirely satisfied with CERP’s compromises, but no one would be happy without CERP either. “The Everglades Coalition supports the [CERP] process,” insists Martin. But he adds, “We would like CERP to go in a more extensive direction….We want to see more natural areas….We need much more land than anybody’s putting aside right now.”

Until CERP can deliver on its promises, perhaps three decades from now, hope, like the Everglades ecosystem, will remain on life support.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment