... cover for the ambulance bays, steel for a shoring platform and steel for a fifth-floor pedestrian bridge connecting the new building to an existing one across the street. That operation was done on Saturday and Sunday.

An operator is not needed in the cab 24/7, unless there is bad weather, such as high winds. So far, Craig has pulled about eight all-nighters, says Doug Bonds, BB’s senior project manager.

| + click to enlarge |

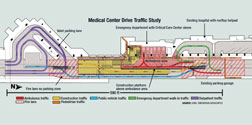

Medical Center Drive Traffic Study

|

All told, 13% of the time the crane is in operation it is shut down, says Bonds. The CM anticipated this in advance of construction by analyzing Life Flight’s historical data during the job’s planning phase.

The full team started planning the project in 2003, some two years before any schematic drawings were issued and three years before construction started.

One of the cures for the job’s ills is a $1-million steel-framed-truss shoring platform over the emergency department (ED) to protect its roof. This included the 170-ft x 58-ft shed over the street and ambulance bays.

The shed roof doubles as the job’s only laydown and staging area. The limited space means just-in-time deliveries for all equipment and materials. That required very careful planning and coordination, says Bonds.

The crane tower’s location was another head-scratcher. The proximal neighbors and active street ruled out a building-perimeter crane tower. Instead, BB put the crane tower straight through the ED. “This creates further problems finishing the building” but it avoids getting in the way of the ambulances, says Travis.

Dana Thomas Photography Roof of cover to protect ambulances is staging area.

|

Hours for surgery in the existing hospital are from about 6:30 a.m. to 8 p.m. That meant limits on construction noise and vibrations. Consequently, workers from local Charter Construction cast concrete at night, using pumps. At one point during the day, workers were dropping 2x4s for formwork onto the third floor from waist height. The impact, 150 ft away, was felt by the surgeons. “We had to instruct workers how to do it another way,” says Vanderbilt’s Tenpenny.

A similar situation occurred when crews were dropping bricks stripped from the existing hospital’s facade in preparation for the tie-in to the new structure. The solution was to put foam on the floor to cushion the bricks’ landing, says Tenpenny.

The plan had been to close 50 patient rooms that look onto the jobsite. But the team got permission from Tennessee’s health department to keep the rooms in use. They simply provided protective window coverings—opaque for privacy and set far enough away so the windows could still open for ventilation as required by code. “That allowed Vanderbilt to provide over 12,000 patient days that would have been lost,” says Tenpenny.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment